Metropolis, the great city of the future, is divided into two worlds: the high-rise towers in which the wealthy live and the subterranean depths that house the workers. When Maria brings a group of workers' children into the upper areas, Freder, the son of the wealthy industrialist Joh Fredersen, falls in love with her. Before long, he's followed her into the depths of the city to try to understand the plight of the workers. At the same time, Maria's glimpse at the life of the privileged inspires her to preach equality to her fellow workers. To prevent a revolution, Jon gets the eccentric scientist Rotwang to capture Maria and create an evil robot duplicate of her so he can use the workers' movement to his own ends.

Metropolis was in production for almost a year and a half. It started filming May 22, 1925, and ended on October 30, 1926. With optical printers not yet invented, matte effects were created using a mirror placed at an angle to reflect the art department's drawings. The silvering was scraped off the back of the mirror at the places where the actors and full-sized sets needed to be seen. Cinematographer Eugen Schufftan developed the technique, which is still referred to as The Schufftan Process, for a planned production of Gulliver's Travels. When that fell through, he introduced it on Metropolis. The paintings reflected included the upper levels of the towering buildings (only the lower levels were actually built), the stadium in the wealthy part of town and a large bust of Fredersen's late wife.

The establishing shots of the city—with cars, planes and elevated trains moving about—were shot using stop-motion photography. The cars were modeled on the newest taxicabs driving the streets of Berlin. It took months to build the city model and several days to film the few short sequences. Then the lab ruined the first shots. The backgrounds in the shot had been dimly lit to create a greater sense of depth, but the head of the lab, who developed the film himself, decided that was a mistake and lightened the backgrounds, thereby destroying the sense of forced perspective. All multiple exposures were done in camera, with the film rewound and re-exposed. For some scenes, this required up to 30 different exposures.

Lang started shooting the film with a different actor cast as Freder. During the early days of shooting, however, author of the "Metropolis" novel Thea von Harbou noticed the good-looking Gustav Frohlich, one of the extras cast as a worker. When the first rushes featuring Freder proved unsatisfactory, she urged Lang to let their original actor go and cast Frohlich in the part.

The nightmare in which workers are fed to Moloch was filmed in the middle of winter. Despite the lights and several heaters, the studio was extremely cold, a special hardship on the extras, most of them unemployed men, who had to walk naked into the mouth of the god. Lang took so many days filming the sequence, his assistants feared the extras would revolt. Finally, UFA studio head Erich Pommer came to the set and informed the director that he had more than enough footage already and needed to stop.

For the explosion of the heart machine, Lang refused to use dummies as stand-ins for the workers thrown about. He insisted it would look phony. So extras were to be hooked to harness belts and thrown through smoke, steam and fire. To lighten the mood before shooting, he insisted that his assistant, Gustav Puttscher, try out the harness and then had him yanked almost to the top of the soundstage and left him there. During filming, he insisted the extras show pain, even though there were no close-ups. Incidentally, they already were in pain.

Lang wanted 4,000 bald extras for the Tower of Babel sequence, but Pommer could only find 1,000 willing to shave their heads. Since the scene was shot in the spring, these extras sweltered under the hot sun shooting the exteriors as they hauled prop rocks and real tree trunks across the landscape. Some got sunburns on their scalps from the lengthy shoot. After shooting, Lang ordered the shot run through the optical multiplier to make the 1,000 extras seem like the 4,000 he had originally wanted.

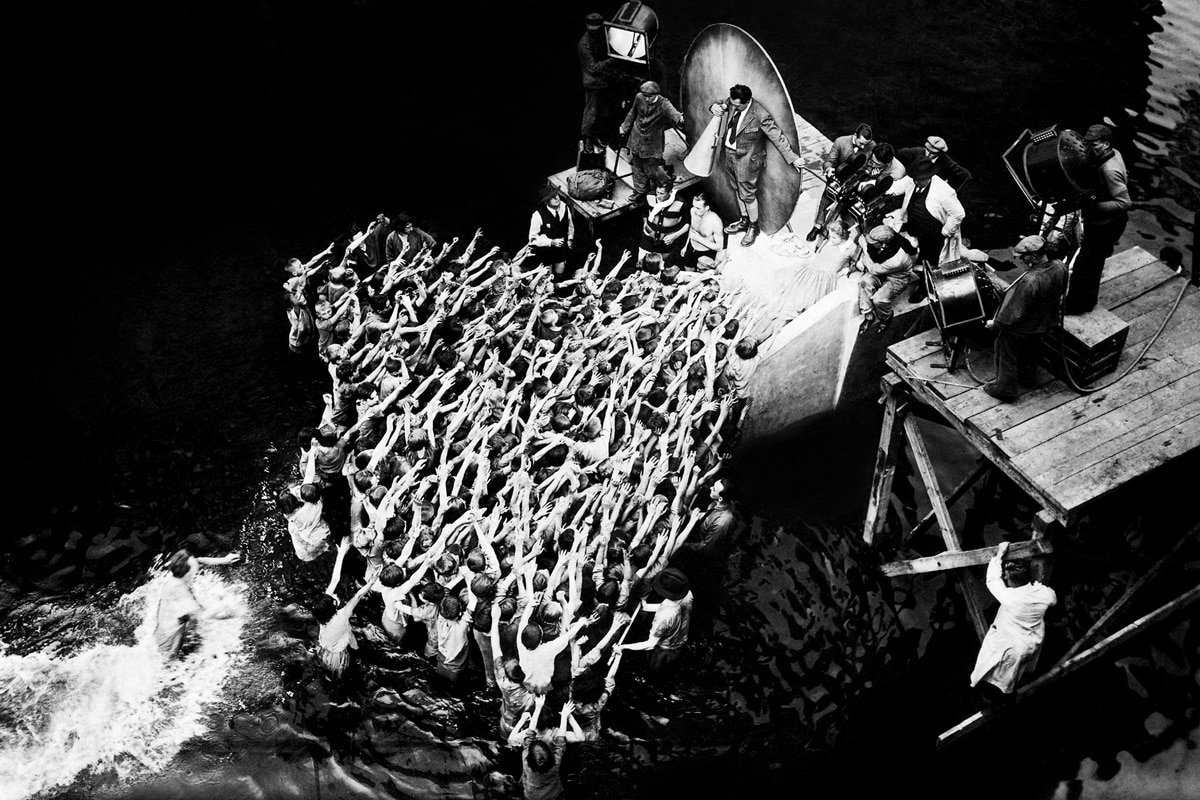

It took 14 days to film the scene in which the worker's city is flooded. Lang hired 500 children from the poorest areas of Berlin and kept them and Brigitte Helm in water he ordered kept cold. While shooting the flood scenes, he repeatedly ordered the extras to throw themselves at powerful jets of water until they were exhausted.

In January 1926, UFA executives met to determine what to do about the increasingly costly production, which seemed nowhere near completion. They considered pulling the plug, but instead settled on firing Pommer from his position as head of the studio. He continued running interference on the production until April, when he left for a job at Paramount Pictures in the U.S.

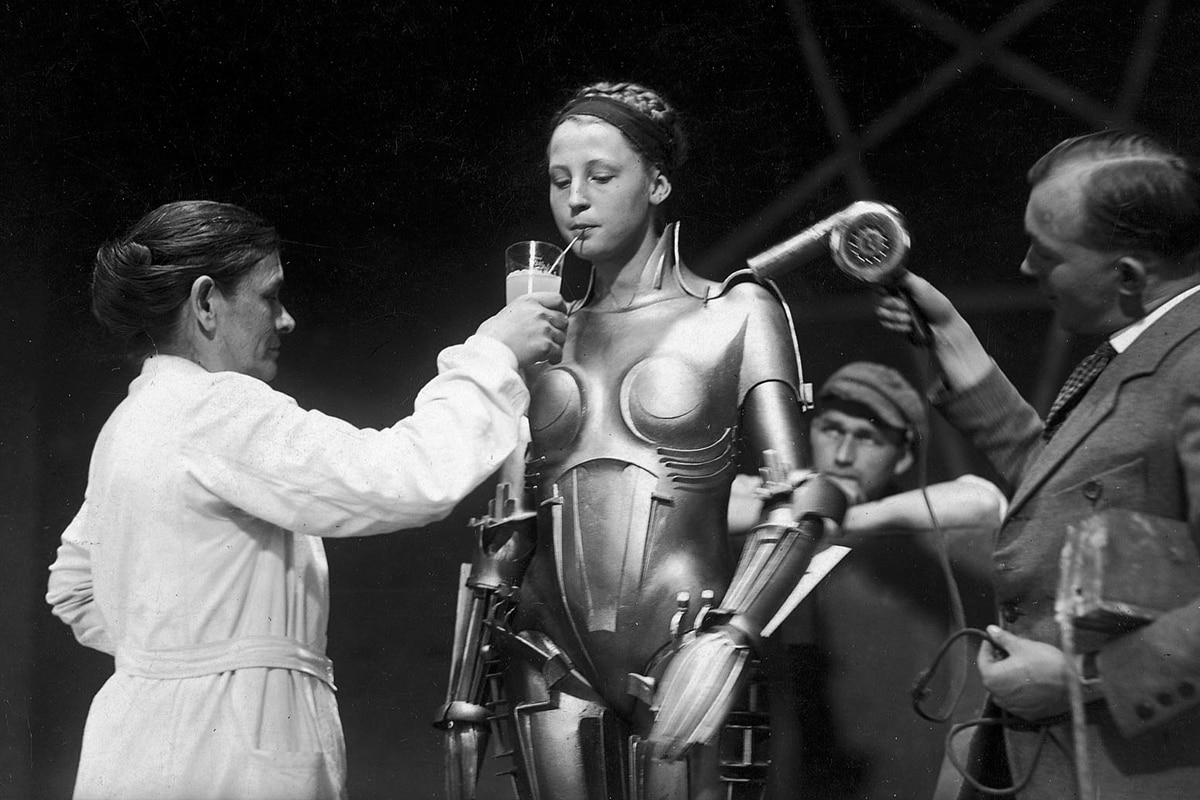

For the chase across the rooftops, Brigitte Helm and Rudolph Klein-Rogge actually had to climb across the tops of the exterior sets and race on planks 25 feet above the ground. At the end of that sequence, Helm, without the benefit of a stunt woman, had to leap for the rope attached to the cathedral's bells. Although mattresses were placed in the event of a fall, the height would still make the stunt dangerous. She caught the rope on the first try, and then slowly slid down it as the ringing bell sent her careening into the set's walls. Bruised and battered, she fled the set in tears.

The scene in which scantily clad dancers and nightclub patrons spill out into the streets was filmed on a chilly spring night. It was so cold that, to keep the extras from rebelling, Lang ordered flasks of cognac for them. When that ran out, actor Alfred Abel offered his coat to one of the dancers.

To build excitement for Metropolis, von Harbou's novel was serialized in the popular German magazine “Illustriertes Blatt” in the months preceding the film's release. At the film's premiere in Berlin on January 10, 1927, the audience burst into applause at some of the more spectacular scenes. At two and a half hours in length, Metropolis could not be shown enough times in a day to return UFA's investment soon enough. As a result, the entire company was restructured, with a new, more conservative board of directors. Appalled at the film's Marxist politics, they pulled it from theatres in the spring of 1927.

As production costs pushed UFA toward bankruptcy, the studio had signed a deal with Paramount Pictures and MGM that created Parafumet to release the two U.S. studios' films in Germany. It also gave the studios distribution rights in the U.S. and other territories to UFA's films and the right to alter those films as they saw fit. Parafumet cut the picture to about 115 minutes, excising the Thin Man's pursuit of Freder and Josaphat and much of the backstory about Rotwang's past romantic rivalry with Fredersen.

For the U.S. version, Paramount hired playwright Channing Pollock to rewrite the film around Lang's footage. He created an entirely new story that blamed all of the action on a greedy employee and identified many of the revolting workers as soulless robots. For the film's U.S. release, Paramount replaced the UFA logo with its own and reshot the credits. Lang refused to see this version. With UFA still in financial difficulties, businessman Alfred Hunberg took charge of the studio. He cut the film still further to remove any Marxist and religious materials.

Director: Fritz Lang

Producer: Erich Pommer

Screenplay: Thea von Harbou

Cinematography: Karl Freund, Gunther Rittau, Walter Ruttmann

Score: Gottfried Huppertz Art Direction: Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht

Cast: Alfred Abel (Joh Fredersen), Gustav Frohlich (Freder), Rudolf Klein-Rogge (C.A. Rotwang), Fritz Rasp (The Thin Man), Theodor Loos (Josaphat), Brigitte Helm (The Creative Man/The Machine Man/Death/The Seven Deadly Sins/Maria)

BW -153 m