Carol King, Trixie Lorraine and Polly Parker, three out-of-work showgirls living together in a cheap New York City apartment, are down to their last pair of stockings when rival Fay Fortune informs them that Broadway producer Barney Hopkins is putting on a show. Carol brings Barney to the apartment, where the girls have gathered their friends, including Polly's boyfriend, Brad Roberts, an aspiring songwriter, to audition. After Barney hears the songs, he admits that he has no backers, but Brad offers to put up the money on the condition that Polly is featured in the show. Trixie and Carol are convinced that Brad is broke and has stolen the money. The show goes on with great success, but Brad’s true identity is eventually revealed, complicating his plans to marry Polly and leading Trixie and Carol into a plot of mistaken identity as gold diggers in Depression-era America.

In some ways, Gold Diggers of 1933 might almost be seen as a sequel to the Warner Bros. blockbuster musical released a few months earlier, 42nd Street. Knowing a good team when it had one, the studio brought in the earlier film's dance director Busby Berkeley, songwriters Harry Warren and Al Dubin, screenwriter James Seymour, cinematographer Sol Polito and five cast members: Ruby Keeler, Dick Powell, Ned Sparks, Ginger Rogers and Guy Kibbee. Quite likely some of the chorus girls were the same, as was future B movie leading man Dennis O'Keefe, who appears uncredited in both movies as a chorus boy. A sixth 42nd Street cast member, George Brent, was initially considered for the role played by Warren William.

Ginger Rogers had been playing mostly minor roles since 1929, when she got a break as "Anytime Annie" in 42nd Street. She was given a more plum role as a similar character in this production (it’s been widely speculated that was because she was in a romantic relationship with director Mervyn LeRoy at the time). In 1970, Joan Blondell shared some memories of this film, and the many other musicals made at Warner Bros. in the 1930s, with John Kobal, quoted in his collection of interviews, “People Will Talk.” She said making these films was tougher than a straight dramatic movie because the cast and crew would frequently work from 6:00 in the morning until midnight and all day on Saturday. She also noted that Dick Powell hated singing and playing the juvenile leads over and over. In the movie, there is an in-joke related to that, when the stage production's lead protests that he has been a juvenile for 18 years.

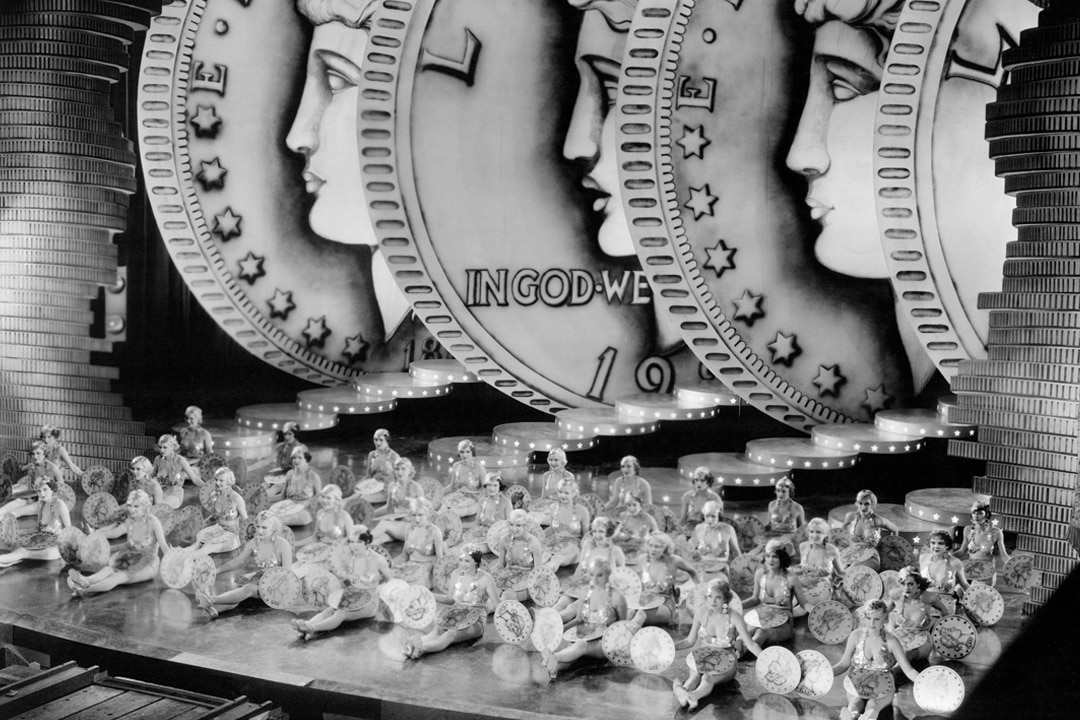

As with 42nd Street, this film was shot with two separate units. Director Mervyn LeRoy's unit, which handled the non-musical parts of the story, worked on a 30-day schedule from February 16, through March 23, 1933. Berkeley oversaw the shooting of the musical numbers between March 6 and April 13. Sol Polito was the cinematographer for both units, with Sid Hickox filling in for any schedule conflicts. According to some sources, the stage for musical numbers was lifted 40 feet in order to achieve sweeping crane shots.

Rogers was goofing around on the set one day during a long rehearsal, translating the opening number, "We're in the Money," into Pig Latin, the nonsense language formed by taking the first letter off a word, putting it at the end and adding the syllable "ay." According to her autobiography, it was Warners production chief Darryl Zanuck who heard her, loved it and instructed her to tell director Mervyn LeRoy to incorporate it into the song. According to Berkeley, he was the one who discovered her singing it and decided to use it in the picture.

On March 10, during filming of the "Shadow Waltz" number, the Long Beach earthquake hit, causing a power outage and short-circuiting some of the lighted violins used by the dancers, dangerously shocking some of them. Berkeley was nearly thrown from the camera boom and hung on by one hand until he could pull himself back up. He yelled for the girls, many of whom were as high up as 30 feet on their platforms, to sit down until technicians could open the doors and get some light into the soundstage.

According to “Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood” by Mark A. Vieira, Gold Diggers of 1933 was one of the first American films made and distributed with alternate footage in order to circumvent censorship problems. Various state censorship boards had their own standards to impose on motion pictures, so studios began filming slightly different versions of problematic scenes, which were then inserted into prints that were labeled to indicate which version would be sent to which state (or country). This picture, with risqué numbers like "Pettin' in the Park," had to make various adjustments to accommodate censors in different areas.

The "Pettin' in the Park" number was originally planned to end the film. When Jack Warner saw Berkeley's "Remember My Forgotten Man" number, he was so impressed, he ordered it to be the film's finale, and "Pettin' in the Park" was moved to earlier in the story. In the scene just before the Forgotten Man number, the stars are seen in their costumes for the "Pettin' in the Park" scene, because they were dressed to go on stage for that number next.

The singer in the "Remember My Forgotten Man" number, who also appears on screen (uncredited) as a war widow, is Etta Moten, who had appeared in bits in earlier movies and dubbed the singing voices for other actresses. Reportedly, Rogers had an additional number in the movie, dressed in black sequins and standing at a white piano in the nightclub sequence. Sources have suggested it was likely a reprise of "I've Got to Sing a Torch Song" performed earlier by Powell. The final cost of the production is estimated at $433,000. The picture went into general release on May 27, 1933.