The creation of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) was as big an epic as the movie itself. Employing teams of professionals in every field from space flight to food services, Stanley Kubrick set out to make what he simply described as a "good science fiction film." His first step was to contact famed writer Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote the short story "The Sentinel" in 1950. Over the next four years, the two men crafted a "fictionalized science lesson" intended to be a coming of age for the entire human race.

On the surface, 2001: A Space Odyssey tells the story of humankind's steps from cavemen to enlightened beings while exploring the complications of sentient technology. However, it is difficult to describe the film’s events in too much detail without spoiling many of the plot points or ruining Kubrick's intention for the film, which was for audiences to "experience" rather than merely "watch." With the help of Clarke, Kubrick wanted to create the kind of science fiction film that just wasn't made before 2001: A Space Odyssey. A voracious fan of science fiction, Kubrick didn't want to merely tell a story about space, he wanted to tell a story about man's relationship to the universe. Because of the immense detail required in a screenplay, Kubrick and Clarke started by writing the story as a novel, which would be primarily Clarke's task. After Clarke delivered the story as a gift to Kubrick on Christmas in 1964, they began converting the plot into a screenplay and the adventure began.

One of the crowning achievements of 2001: A Space Odyssey is its level of detail, which surpassed even Kubrick's usual demands. With the help of scientific consultant Frederick Ordway, the production collaborated with companies like Whirlpool, RCA, GE, IBM, Pan Am and NASA to provide technological product placement. In exchange for discussing their plans for the future and providing feasible designs for futuristic devices, cooperating companies would earn a place in the movie's environments. Hence, 2001 is littered with amusing logos like Pan Am on the shuttle and Howard Johnson's on the hotel in the space station. These little touches make life in space that much more believable.

This same commitment to detail was extended to the groundbreaking special effects in the film. During the “Dawn of Man” sequence, Kubrick employed front projection rather than rear projection, which was more common. Kubrick felt that rear projection never looked convincing, so he mounted a projector from above and projected the background slide behind the set pieces at very low light. The result is a realistic environment. But without convincing ape-men, the background would have gone entirely to waste, so Kubrick employed British makeup artist Stuart Freeborn to bring early man to life.

The actors hired to play the apes in the "Dawn of Man" sequence were mostly mimes and dancers, though they also used two baby chimpanzees as the tribe's children. They chose actors with thin arms and legs and narrow hips so that the fur added to make them look like apes wouldn't appear too bulky. Freeborn's complex masks and prosthetics allowed the actors to articulate their lips convincingly. Freeborn went on to design creatures for the Star Wars films.

The space sequences in 2001: A Space Odyssey proved no less imaginative. Because characters would be traveling and living in a variety of environments onboard spaceships, Kubrick needed to find a realistic way to blend both gravity and weightless conditions. The techniques ranged from the simple – like mounting a pen on a piece of rotating plexiglass so that it appeared to float – to physically rotating the set, while the actors roamed about inside. The weightless space walk sequences were achieved by suspending actors, and in some cases set pieces like the "pod" transports, from the ceiling by wires. The "floating" actors were then shot from below, their bodies hiding the wires.

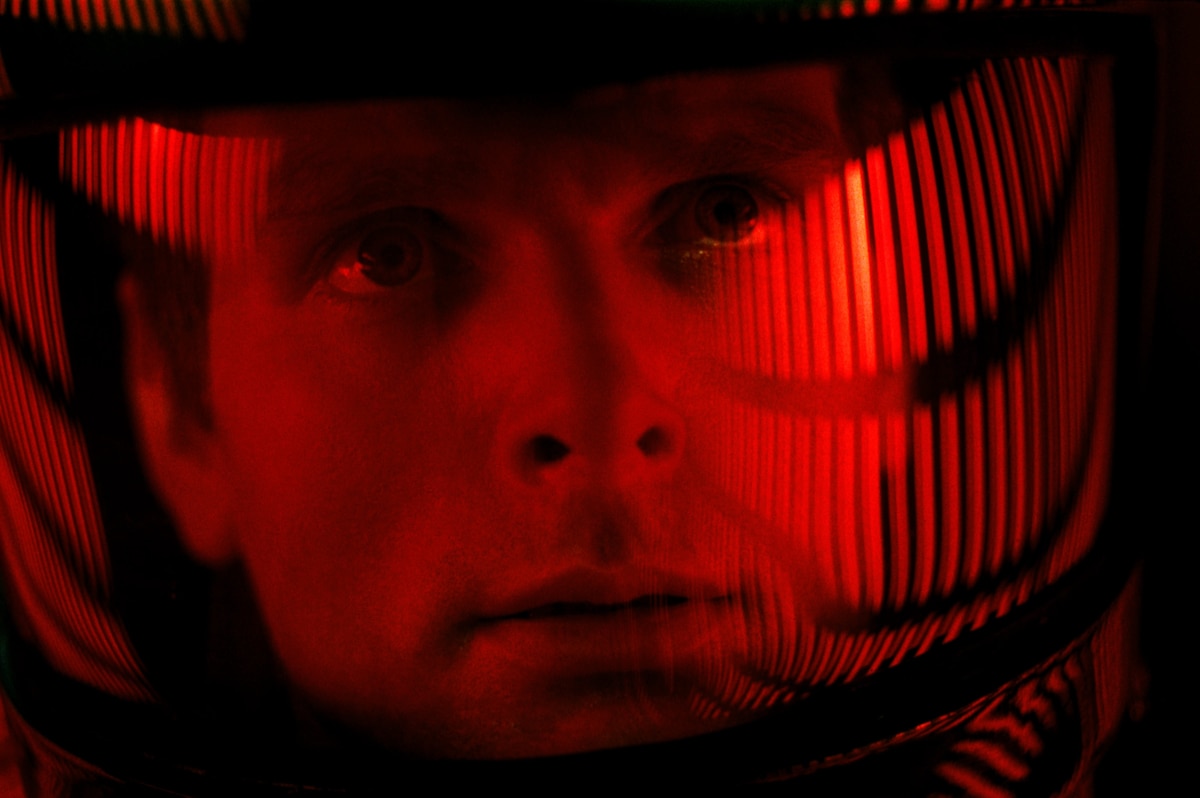

For the "stargate" sequence, visual effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull devised what was called a "slitscan machine." The machine helped with the process of photographing backlit transparencies of artwork, exposing each frame for a full minute, then moving the camera and artwork in sync, recording the art with a "streaked," stylized fashion. The result was the appearance that Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) was moving through time and space at infinite speeds. To create convincing images of nebular movement and starbursts, they photographed drops of dye moving on a glass plate. Filming the special effects shots alone took 18 months and cost $6.5 million. In total, production took just over four years and cost MGM roughly $11 million.

2001: A Space Odyssey was met with mixed reviews when it premiered on April 12, 1968. Critics were divided on the film with some calling it slow, boring and confusing. Luckily, for Kubrick and Clarke, 2001: A Space Odyssey struck a chord with younger audiences, and subsequent re-releases made the film one of the biggest box-office draws of 1968. According to “Rolling Stone” magazine, during one screening a young man rose as if in a trance at the monolith's reappearance near the end and ran down the theatre's aisle shouting, "It's God! It's God!" Before the theatre's management could stop him, he had crashed through the screen.

2001: A Space Odyssey is now widely praised as a remarkable achievement for its realistic depiction of space flight during a time when our space program was in its infancy. Years before we actually set foot on the moon, Kubrick and Clarke not only envisioned settlements there; they showed us an unsettlingly accurate portrayal of the lunar surface. Nevertheless, the film can be undoubtedly confusing – a point that Clarke concedes. During a trip to Hawaii from his home in Sri Lanka, Clarke was detained by an immigration official who joked, "I'm not going to let you in until you explain the ending of 2001 to me." But the film's ambiguity is part of its importance. Had Kubrick spelled it out entirely, he would have robbed viewers of the experience, and we would not still debate it today. As Kubrick himself commented, "It's a nonverbal experience – the truth is in the feel of it, not the think of it."

Director/ Producer: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, based on the story "The Sentinel" by Arthur C. Clarke

Cinematography: Geoffrey Unsworth

Editor: Ray Lovejoy

Art Direction: John Hoesli

Music: Aram Khachaturyan, Gyorgy Ligeti, Richard Strauss, Johann Strauss

Cast: Keir Dullea (Dr. Dave Bowman), Gary Lockwood (Dr. Frank Poole), William Sylvester (Dr. Heywood R. Floyd), Daniel Richter (Moonwatcher), Leonard Rossiter (Smyslov), Douglas Rain (voice of Hal 9000).

C-149m. Letterboxed. Closed captioning. Descriptive Video.