February 2–9 | 45 Shorts

Like many immortal stars, you know who Bugs Bunny is even if you’ve never seen any of his work. His line, “Eh…What’s up, Doc?”, his wise-cracking attitude and his penchant for outsmarting his opponents have made him an indelible figure in the firmament of American entertainment. There was a time when the very Warner Bros. logo wouldn’t spin without Bugs present right beside it. With the exception of Mickey Mouse, no figure has been so synonymous with a studio throughout its lifetime. TCM will spend the first week of February honoring the carrot-chomping icon and how his shorts provide fun reflections of his cinematic and cultural contemporaries, as well as the classics.

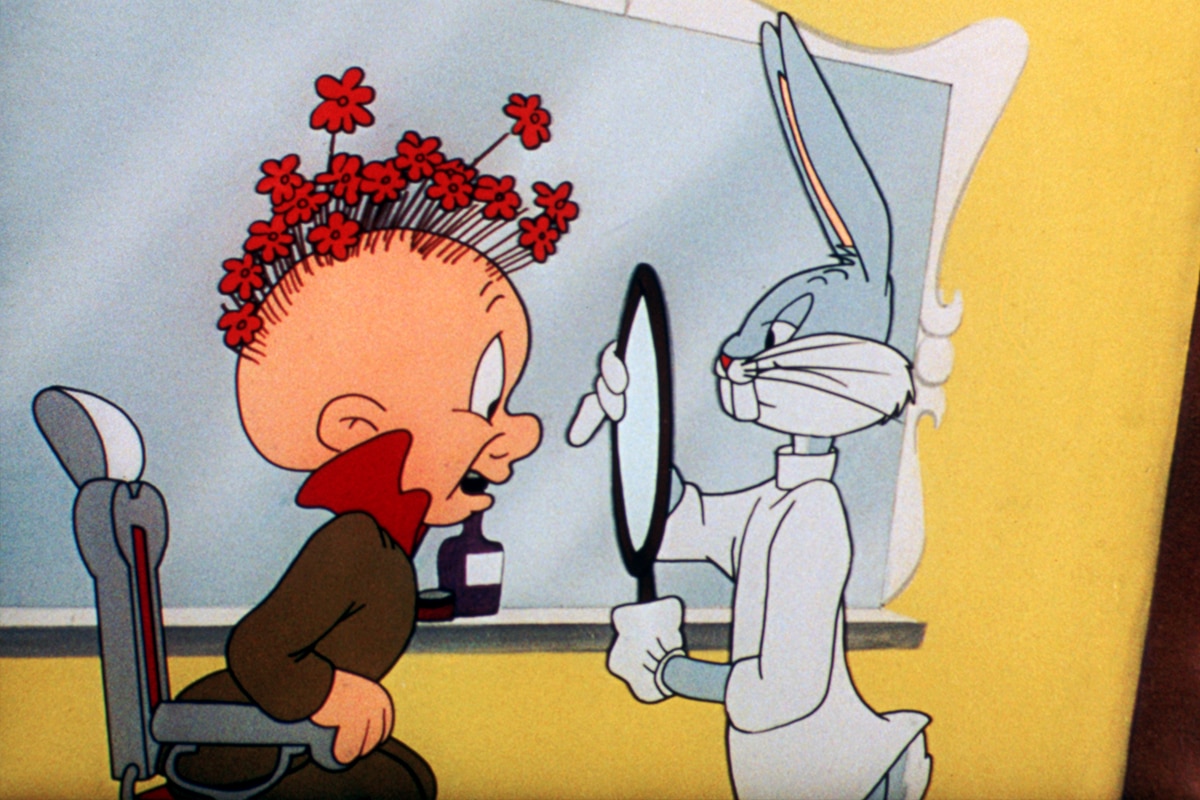

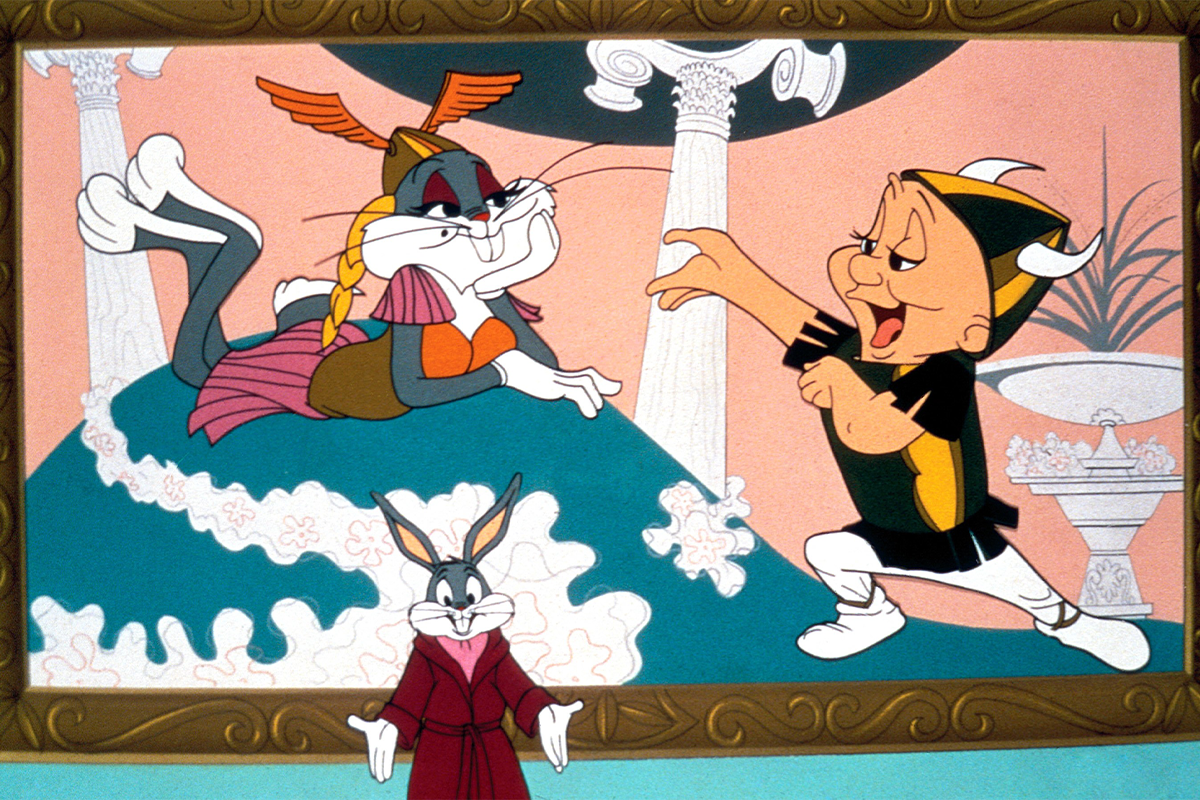

Although an early iteration of Bugs Bunny appeared in “Porky’s Hare Hunt” (1938), the character definitively debuted in Tex Avery’s 1940 short “A Wild Hare,” where he squares off against his future long-time nemesis, hunter Elmer Fudd. Although Bugs would go through a few design refinements over the next decade or so, he emerges almost fully formed in “A Wild Hare,” voiced by Mel Blanc with all of his trickster antics in place and his knack for outsmarting almost any rival. With Elmer Fudd and Bugs’ feud eternally set, the animators at Warner Bros. clearly had a blast finding new and interesting ways to set the two against each other, as you can see with the opera-influenced “Rabbit of Seville” (1950) and “What’s Opera, Doc?” (1957).

While the opera makes for a clear lead-in for the first night’s Marx Brothers’ classic A Night at the Opera (1935), you can also see the huge influence that Groucho Marx, as well as Clark Gable, had on the character of Bugs Bunny. While Bugs, as a children’s cartoon, could never have Groucho’s signature cigar, the carrot made for a good stand-in (although carrots should only be an occasional treat for rabbits). More importantly, the way Groucho always has a quick comeback and a way of outsmarting those around him is reflected in the way Bugs plays off Elmer Fudd, Daffy Duck, Yosemite Sam and others. Although Bugs doesn’t carry over Groucho’s self-deprecation, you can see quite a bit of overlap between the two comic giants.

Bugs Bunny has always had the flexibility to be a character in conversation with contemporary culture. Sometimes that’s fairly broad, as you can see when Bugs Bunny is at sea and you get a short like “Captain Hareblower” (1954), an adaptation of 1937 literary character Horatio Hornblower, whose first screen adaptation arrived in 1951 with Gregory Peck in the title role. Other times, it’s about sending Bugs into a particular genre like science fiction where he could square off against Marvin the Martian in shorts such as “Haredevil Hare” (1948) and “Hare-way to the Stars” (1958). You could also send Bugs Bunny into the gangster genre, as he goes against Rocky and Mugsy in “Bugs and Thugs” (1954), “Bugsy and Mugsy” (1957) and “The Unmentionables” (1963).

Audiences could easily get on board with Bugs’s antics because they were aware of the broad parody and genre tropes being sent up by the animators at Warner Bros. While Bugs’s jabs could be sharp, the shorts themselves tended to be loving spoofs that took what audiences knew and used the elasticity of animation paired with the bunny’s wise cracks to playfully poke at the studio’s own features like The Roaring Twenties (1939). This would lead to a fun interplay where Hollywood’s Golden Age would build up foundational genre tropes only for a character like Bugs to come along and knock them back down.

Pitting Bugs against contemporary cinema was fun, but he was also just as useful in classic literature. One of the few times Bugs “loses” is when he’s going through adaptations of Aesop’s “The Tortoise and the Hare,” which sets the rabbit against Cecil Turtle. Although the classic story was about a hare who was too overconfident to properly prepare against his slow-and-steady opponent, these shorts featuring Cecil show the tortoise getting one over on Bugs, like when Cecil is able to recruit his family in “Tortoise Beats Hare” (1941) and then a rematch in “Tortoise Wins by a Hare” (1943) that also has Cecil outwitting Bugs.

Sometimes playing into the classics wasn’t so much about using an exact story but an entire genre. Opera provided a perfect juxtaposition with its grandiose, high-culture refinement coming into the “Looney Tunes” world, where viewers wouldn’t need to know the plot of “The Barber of Seville” (although they certainly would have heard its public domain music) to appreciate the blending of familiar tunes with barbershop gags. Even in “What’s Opera, Doc?,” the animation leans all the way in, relishing the operatic setting with some striking visuals while playing Elmer and Bugs into Wagner’s operas and having Bugs break the fourth wall by asking us, “Well, what did you expect in an opera, a happy ending?”

One of the benefits of using fairy tales or classic stories is that all the plot work and framing is done for the audience. For the short “Little Red Riding Rabbit” (1944), we know from the title what that short will use as its basis before heading off into a comic direction. The shorts could even turn literature on its head, creating a world where it’s the classic work that was inspired by “Looney Tunes” instead of vice versa. Look at 1959’s “A Witch’s Tangled Hare,” which uses the character Witch Hazel to “inspire” “Macbeth.” And if you’ve still got a hankering for Shakespeare after that short, you can watch Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948) and George Cukor’s Romeo and Juliet (1936).

Bugs wasn’t constrained to adapting narratives. While “Looney Tunes” could play off popular movies and classic tales, there’s a remarkable blend of high culture and older works, and you can see this through the “Rabbit Rhapsodies” lineup on Wednesday, February 4th, with “A Corny Concerto” (1943), using the music of Johann Strauss; “Rhapsody Rabbit” (1946), employing Franz Liszt (and later inspiring the Donald vs. Daffy scene in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, 1988); and “Baton Bunny” (1959), relying on the work of Franz von Suppé. Bugs doesn’t really talk in these shorts, he instead embraces a lovely blend of music and physical comedy to speak for him.

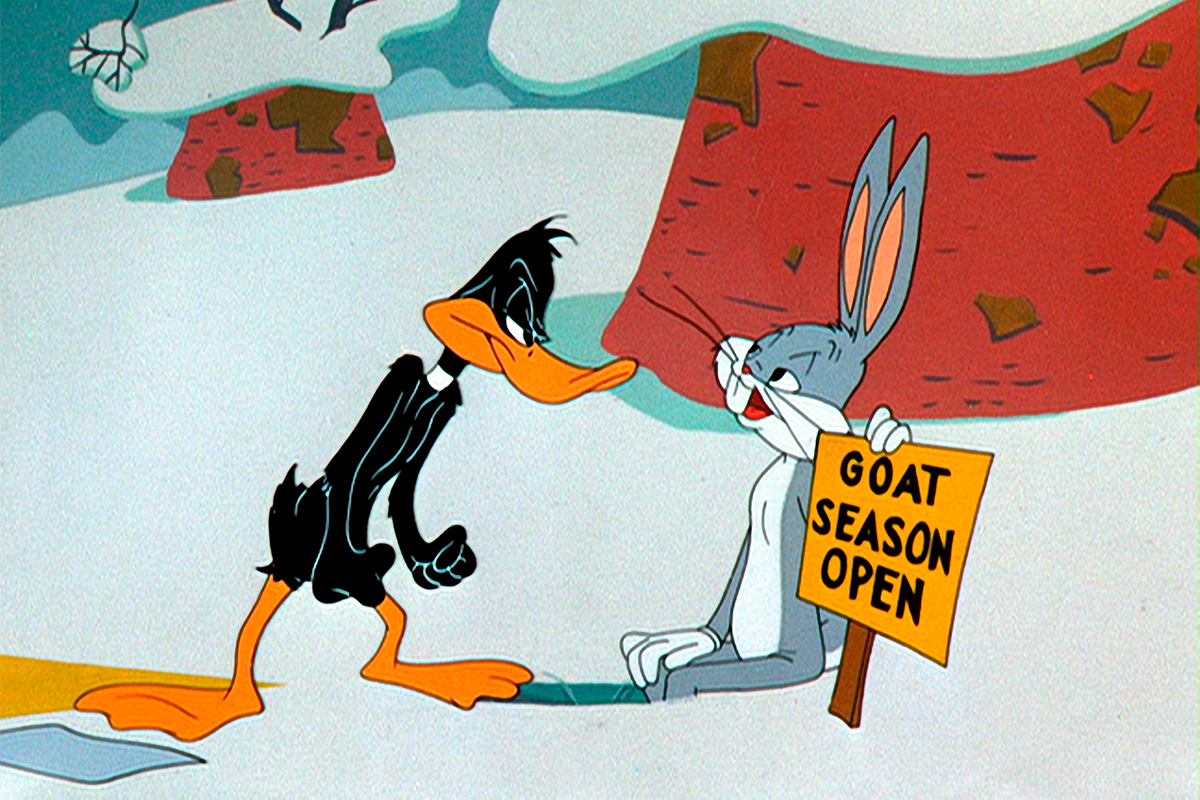

As much as Bugs Bunny can play off classic and contemporary culture, sometimes you also need him in his own little world, and his Star of the Month lineup has that covered as well. Bugs is usually at his best when playing off an adversary, so you not only have Elmer Fudd and Yosemite Sam, but also fellow animals like Wile E. Coyote and Gruesome Gorilla. And yet, no one is as great a counterweight to Bugs as Daffy Duck, whose shorts with Bugs are featured on Friday, February 6th.

These “Looney Tunes” shorts show that as much as the animators could place their characters into larger milieus, they also had clearly defined personalities that could exist within typical woodland settings. The cool, calm, collected Bugs would always be able to outdo the irate, irritable and sardonic Daffy, perhaps nowhere as clear in the classic “Duck! Rabbit, Duck!” (1953), as they feud in directing which hunting season Elmer Fudd should be pursuing. Daffy can never one-up Bugs (and really no one can except the aforementioned Cecil), but he’s arguably the rabbit’s most entertaining nemesis as Daffy’s mission isn’t to kill and eat Bugs Bunny as much as he’s also trying to avoid being Elmer’s dinner.

Given the character’s charm, charisma, creativity and “Ain’t I a stinker?” personality, it’s small wonder that Bugs went from a player in shorts to essentially serving as the studio’s mascot. While Bugs has been featured in movies like Space Jam (1996) and Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003), he shines brightest in his own animated universe, running the show rather than playing animated counterpart to humans who lack his elasticity (Michael Jordan’s long-arm dunk notwithstanding). He’s a scene-stealer who knows he steals scenes and does so with equal measure of wit and lunacy. Even if Bugs Bunny wasn’t blessed with the immortality that animation provides, he would still be as indelible and lasting as any flesh-and-blood performer.