December 8, 15 and 29 at 8pm ET | 16 Movies

Art is a reflection of its time. One hundred years ago, the April 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris officially introduced the world to a new style, born out of the wreckage of World War I. Termed Style Moderne or Art Moderne–later becoming known as Art Deco–it was a drastic departure from the flowery, soft designs of Art Nouveau. Think of the Jazz Age and you think of Art Deco, whether it’s the American streamlined, modernist machine-esque look of the 1920s and 1930s, or the colorful and geometric designs of the French. Over three nights in December, TCM host Dave Karger will discuss the history and significance of Art Deco in Hollywood in our special programming co-curated by Art Deco historian, author, lecturer and former president of the Art Deco Society of Los Angeles, John Thomas.

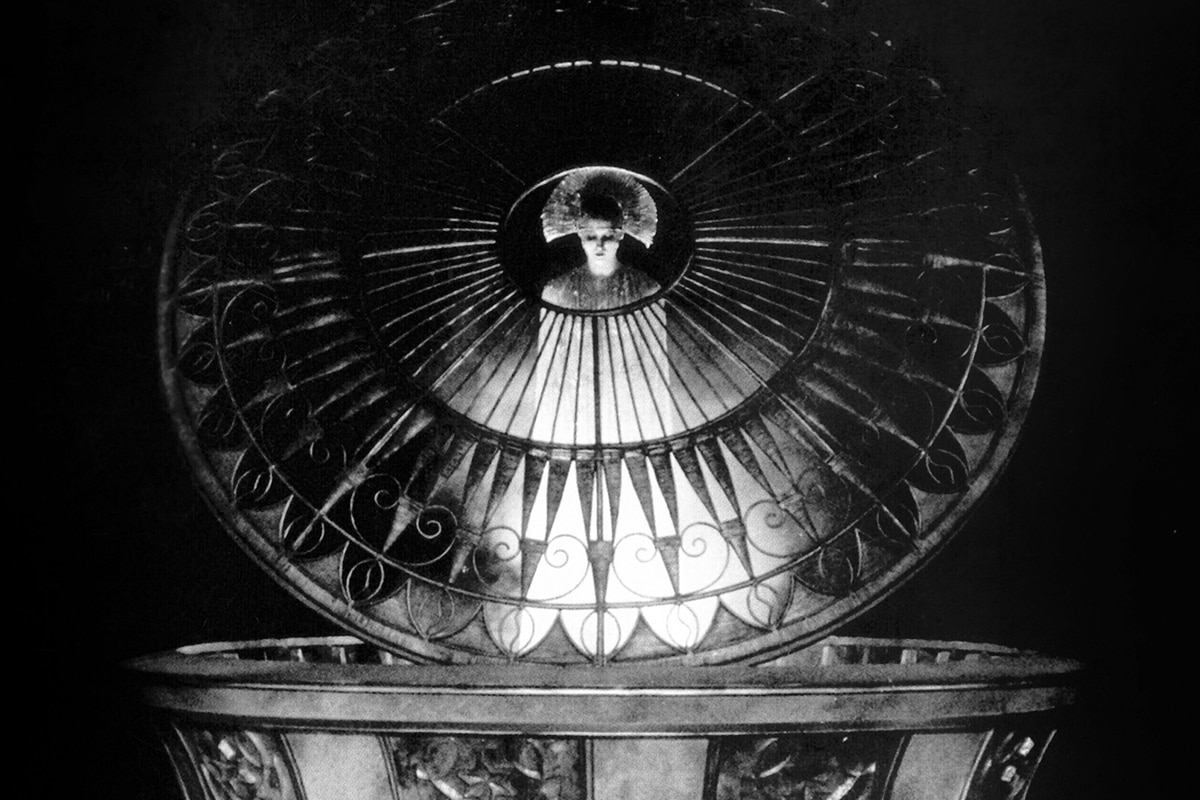

World War I had destroyed lives, countries and a way of life, leaving many frightened, confused and wanting to create a better future. In Germany, whose post-war economic collapse would eventually lead to the rise of Adolf Hitler, the zeitgeist of anxiety was reflected in a new cinematic look that came to be called German Expressionism. The sets were bizarre, with shadows, sharp lines and angles that had no place in reality but reflected the psychology of its characters. Costumes, lighting–even makeup tried to move far away from real life. The look quickly evolved from the cruder style of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to the ultra-modern and still extraordinary art design by Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut and Karl Vollbrecht for Fritz Lang’s masterpiece about the Mechanical Age enslaving humanity, Metropolis (1927). The film utilized many Art Deco elements, like stainless steel, glass, chrome and bakelite plastic, even turning a main character into a metal, Art Deco creature. While Metropolis may be the gold standard for European Art Deco on film, it was not the first to feature the style in architecture. According to author Philip French, Art Deco buildings appeared on film even before the Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes exhibition, like designer Robert Mallet-Stevens’ work in Marcel L'Herbier's L’Inhumaine (1924).

While Grand Hotel (1932) was made at MGM in Los Angeles, it was set in Berlin. Art designer Cedric Gibbons created a circular-shaped hotel with open space that looked straight down into the lobby, where sharply geometric floor tiles and glass are a masterclass on the style. Gibbons had attended and been influenced by the 1925 Paris exhibition. That influence can also be seen in his work in the Joan Crawford-starrer Our Dancing Daughters (1928), which opens with a shot of an Erté-esque statuette, followed by Crawford dancing in front of several mirrors, while she dresses in her ultra-Art Deco bedroom, complete with shiny black floor. Gibbons would continue along similar lines in Crawford’s films, Our Modern Maidens (1929) and Our Blushing Brides (1930). Although Clara Bow created an iconic personification of the flapper in It (1927), Crawford, who was famous for winning the Charleston dance contests at Los Angeles’ Coconut Grove nightclub, gave her a run for her money.

Art Deco was the style of the flapper because of its inclusion of the changing role of women, who had experienced a degree of social freedom outside of the home during WWI and were reluctant to give it up. After decades of struggle, the 19th Amendment finally passed in August 1920, giving women the right to vote in the United States. Although Prohibition was the law of the land, films existed in an alternate dimension where liquor was still served. The flapper drank cocktails, drove automobiles and worked in department stores or offices, and her modern look was a complete departure from the pre-War era. Long, luxuriant hair for women had been the beauty standard for centuries. Now, the flapper announced her freedom by cutting her hair into bobs made famous by Louise Brooks, Colleen Moore and Irene Castle. The absurdly large hats of the early 1900s were replaced with cloche hats that hugged the head, and the ankle-length skirts of the past rose to unprecedented heights.

Nightclubs never looked so good as they did in the films of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, especially in Top Hat (1935), with its stylized version of Venice, and in Swing Time (1936), which features the sparkling, shining black-and-white stairs for the “last dance” scene. The art direction for these and all the RKO Astaire-Rogers films was done by Van Nest Polglase and his crew.

Art Deco buildings began popping up all over the world, and Hollywood was no exception. Offscreen, movie theaters that were owned by the studios were built in various Deco styles. Sid Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre capitalized on the craze for Egyptian art in the 1920s, influenced by the discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. Los Angeles haberdasher-to-the-stars, James Oviatt, had attended the 1925 exhibition and fell in love with the style, instructing his architects and designers to use it for his new building, commonly referred to as the Oviatt Building, completed in 1928. Onscreen, the sharp style of the new skyscrapers appeared in many New York-based films like Skyscraper Souls (1932), another Cedric Gibbons creation. The Art Deco aspects are overwhelming in this film, as almost every shot has horizontal lines running through the sets. Both it, and another Gibbons-designed film, Five and Ten (1931), open with shots of New York skyscrapers.

The most unrealistic and over-the-top Art Deco decor subsided as the Great Depression trudged on, and the world went through the biggest hangover in history. Outlandish and wasteful aesthetics began to wear thin on people who had their financial rug pulled out from under them. By the end of the decade, home and film design returned to a more traditional, realistic and comfortable look. The Women (1939) showcases fashion in a Technicolor sequence, and the villainous Crystal’s (Joan Crawford) bathroom, the health spa and the nightclub ladies’ lounge all have Art Deco elements. By contrast, Mary’s (Norma Shearer) home, while expensive, looks lived in and comfortable, reflecting the fact that she is the most relatable, likable and down-to-earth of all the society women.

The heyday of Art Deco lasted until the end of World War II, then disappeared until a brief revival in the 1980s with the Memphis Design, led by Italian designer Ettore Sottsass. Recently, there has been a renewed interest in Art Deco elements, rather than a strict adherence to the style. And while Art Deco gave way to Mid-Century Modern (a style that returned with a vengeance 20 years ago and is still with us), the architecture of the 1920s and 1930s lives on in nearly every major city in the United States. The Los Angeles Conservancy offers walking tours of some of the best Art Deco buildings in downtown Los Angeles, including James Oviatt’s former haberdashery.

SOURCES:

The AFI Catalog of Feature Films. “Grand Hotel.” https://catalog.afi.com/Film/7720-GRAND-HOTEL?sid=67497a43-e69b-4633-a587-1da7ba52c3e3&sr=10.965615&cp=1&pos=0

The AFI Catalog of Feature Films. “Our Dancing Daughters.” https://catalog.afi.com/Film/11184-OUR-DANCINGDAUGHTERS?sid=ee0c3bca-4b24-4afa-8579-cf646759af9e&sr=12.98125&cp=1&pos=0

Art Deco Society of Los Angeles. “Art Deco Centennial Celebration at the Oviatt Penthouse.” https://artdecola.org/events-calendar/centennial-celebration-oviatt

“100 years of Art Deco” CBS Sunday. YouTube. 2025. https://www.youtube.com/v=-PcjhQhA86.

French, Phillip. “For Fred and Ginger, art deco was the magic movement.” The Guardian. 29 Mar 2003. https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2003/mar/30/features.review77

The Los Angeles Conservancy. “The Oviatt Building.” https://www.laconservancy.org/learn/historic-places/oviatt-building/

“The Rise, Fall and Revival of Art Deco. A Style is Born.” YouTube. 2023. https://www.youtube.com/v=usdi-LL-aG4