December 26 at 8pm ET | 6 Movies

TCM once again concludes its programming year by honoring the actors and film artisans who passed away in 2025. It isn’t accurate to say we lost them, because as long as their work endures, their memory is preserved to captivate and inspire generations to come.

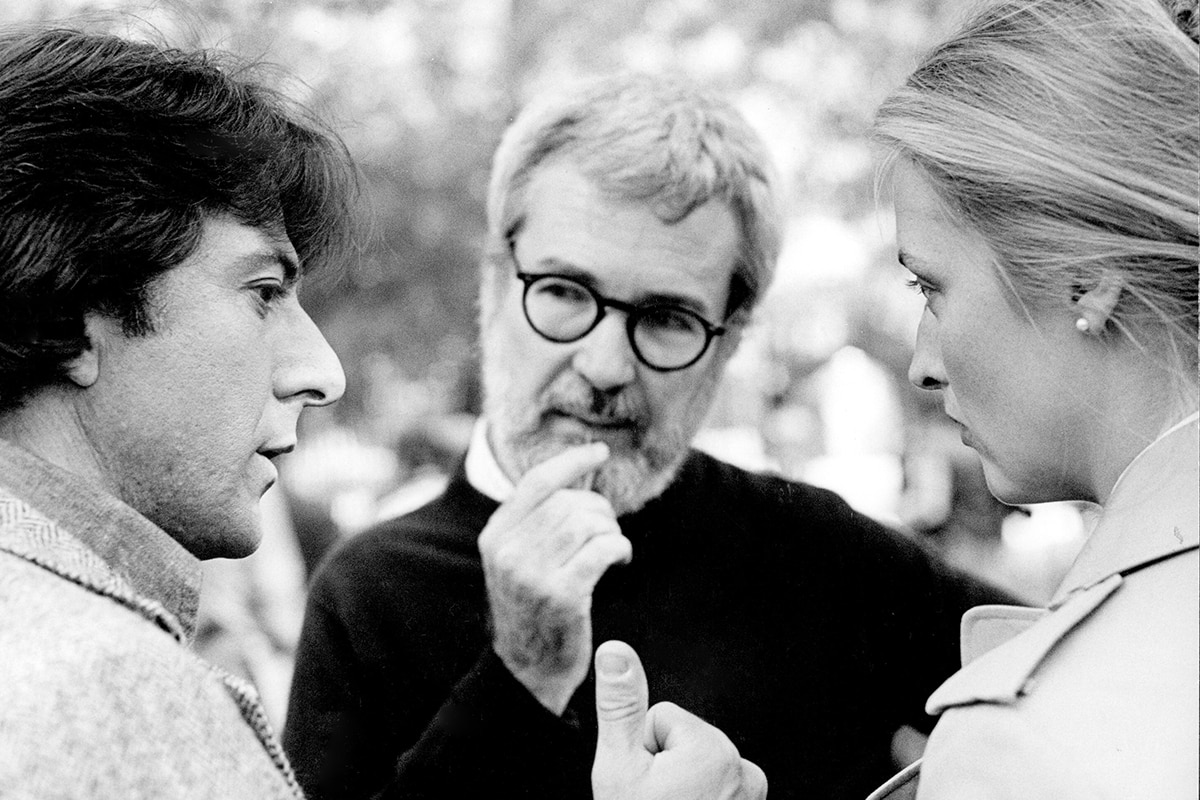

Robert Benton (Kramer vs. Kramer, 1979)

Robert Benton, an Oscar-winning screenwriter and director, once modestly told The Los Angeles Times, “I don’t leave a trace in the mirror.” His scripts and feature films have left a much more indelible impression. He and David Newman co-wrote the script for Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967), which helped to usher in the New Hollywood era in the 1970s. Pauline Kael called it the most important and influential movie of the 1960s. Places in the Heart (1984) earned an Academy Award for its screenplay. As a screenwriter, he was nominated five times, as a director, twice. Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), TCM’s featured film and the highest-grossing film of 1979, earned Oscars for Benton’s direction and screenplay, as well as acting honors for Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep.

Offscreen, Benton began his career as an art director for Esquire magazine. It was Benton who pitched the idea of assembling four decades of jazz musicians for a group photo in 1959, titled “A Great Day in Harlem.” (The Oscar-nominated documentary A Great Day in Harlem [1994] tells the joyous story.) Benton directed only 11 feature films in 35 years. His most successful were more intimate character studies, such as an old school private eye (Art Carney) teamed with a New Age eccentric (Lily Tomlin) in The Late Show (1977) and a small-town father (Paul Newman) who reconnects with his estranged son through his young grandson in Nobody’s Fool (1994). Roger Ebert, in his review of Nobody’s Fool, summed up Benton’s gift when he wrote, “The best moments in the film are based on relationships.” In an interview with Venice magazine, Benton self-effacingly stated, “I’m a director of small things.”

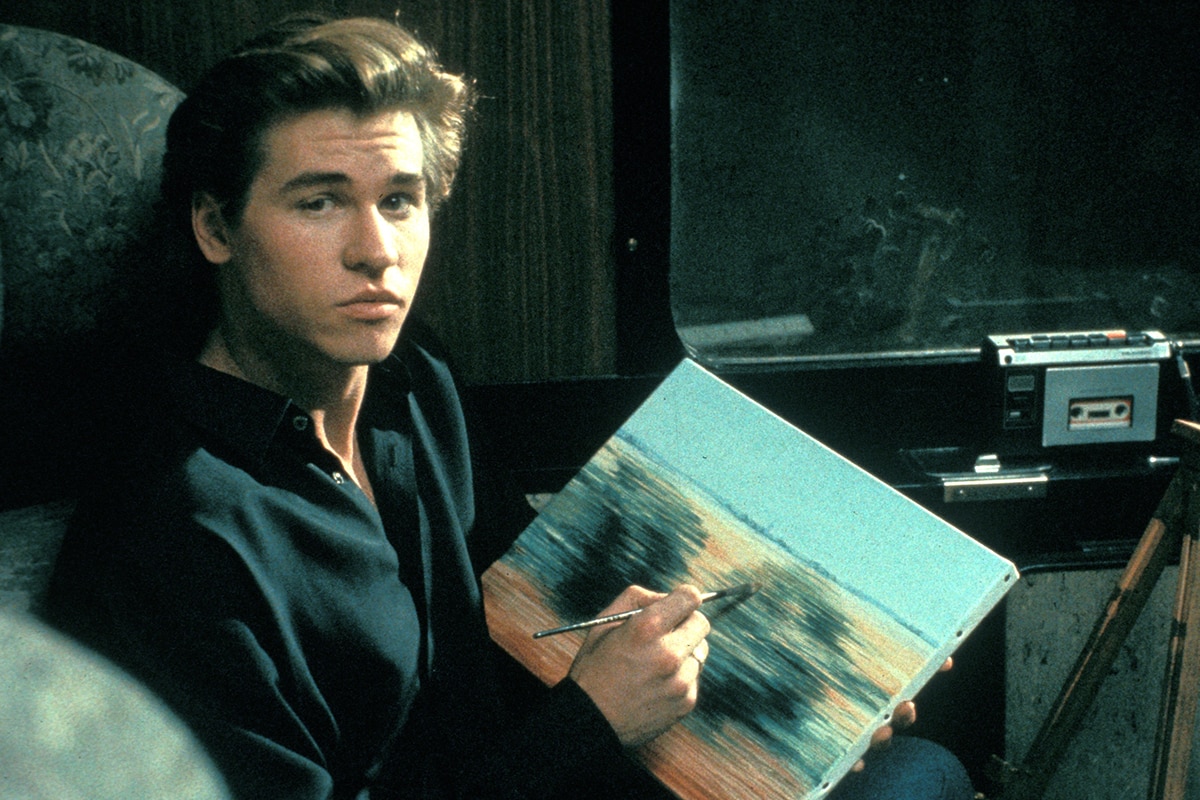

Val Kilmer (Top Secret, 1984)

Top Secret!, the Zucker-Abrahams-Zuker team’s underseen and underrated follow-up to Airplane! (1980) finds Val Kilmer in the first flush of stardom—a deft comic actor and a perfect instrument for ZAZ’s straight-faced absurdities. Kilmer, a throat cancer survivor who died in April of pneumonia at the age of 65, was a character actor with leading-man good looks. He played the Caped Crusader in Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever (1995) and Jim Morrison in Oliver Stone’s The Doors (1991), but his most indelible performances were in iconic supporting roles: Iceman in Top Gun (1986) and its sequel Top Gun: Maverick (2022); Doc “I’m your Huckleberry” Holliday in George P. Cosmatos’ Tombstone (1993); Chris in Michael Mann’s Heat (1995); and the villain Dieter von Cunth in Jorma Taccone’s cult classic MacGruber (2010). Robert Downey Jr., who co-starred with Kilmer in Shane Black’s cult favorite Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005), told The New York Times, “I’m sure this can’t be news to you that he’s chronically eccentric.” Anthony Breznican noted in Vanity Fair that Kilmer “both embraced and shattered the expectations of a Hollywood leading man” over his four-decade career.

One of Kilmer’s conditions for accepting the role in Heat was that he be positioned on the poster between Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. As for signing on to the Batman franchise, he said simply of the much-analyzed character, “Just don’t step on the cape and you’re away.” In 1992, Roger Ebert proclaimed, “If there is an award for the most unsung leading man of his generation, Kilmer should get it. He has shown a range of characters so convincing that it’s likely most people, even now, don’t realize they were looking at the same actor.” Kilmer took a break from Hollywood for over a decade to spend time with his children and pursue other interests, such as touring the country with a one-man play he wrote and performed about Mark Twain, “Citizen Twain.” He told The Hollywood Reporter, “I don’t have any regrets. It’s an adage, but it’s kind of true: once you’re a star, you’re always a star—it’s just what level?”

Joe Don Baker (Walking Tall, 1973)

Joe Don Baker was one of character actor-savant Quentin Tarantino’s favorites. It speaks volumes that Baker is discussed on 15 pages by Tarantino in his film-geek memoir “Cinema Speculation.” Warren Beatty is referenced on only seven. Baker, who died in May at the age of 89, was a prolific character actor on television and in film before the grassroots success of Phil Karlson’s Walking Tall made him a star. Pauline Kael called the film “a volcano of a movie—and in full eruption.” Baker starred as Sheriff Buford Pusser, a real-life figure who became a one-man bat-wielding wrecking crew who cleaned up his corruption-riddled Tennessee hometown. Made for about $500,000, Walking Tall earned more than $40 million globally. Observed Tarantino, “After Walking Tall, Baker ‘was only a little less popular than Elvis Presley.’” In a 1975 Esquire piece, L. M. Kit Carson listed Baker with Robert De Niro and Pam Grier as a new generation of actors leading the way in a new era for Hollywood. A native of Groesbeck, Texas, Baker studied at New York’s prestigious Actors Studio. In a 1986 interview with Bobbie Wygant, she asked how he gained acceptance into the elite program. “I listened,” he said. “I did a scene with a girl, and she did most of the talking, so I listened. Come to find out, that’s what you’re supposed to do when you act is listen.”

He made his Broadway debut in 1963 and his television debut two years later in an episode of “Honey West.” Notable early credits include an unbilled role in Cool Hand Luke (1967), Blake Edwards’ Wild Rovers (1971) and as Steve McQueen’s unscrupulous younger brother in Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner (1972). Baker resisted typecasting by playing a wide variety of characters on both sides of the law. He played a CIA agent in two James Bond films, GoldenEye (1995) and Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), and a villain in a third, The Living Daylights (1987). He was a Babe Ruth type in Barry Levinson’s The Natural (1984), a private detective in Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991), Sen. Joe McCarthy in the HBO production Citizen Cohn (1992), a BAFTA-nominated turn as a CIA agent in the award-winning British miniseries Edge of Darkness (1985) and father to Gen Xer Winona Ryder in Ben Stiller’s Reality Bites (1994). In a career that lasted just over five decades, few actors ever walked taller.

Claude Jarman Jr. (The Yearling, 1946)

Claude Jarman Jr. was 10 years old when he was chosen out of 19,000 candidates by director Clarence Brown to portray Jody, a lonely Florida farm boy who adopts an orphaned fawn in The Yearling (1946). This adaptation of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ 1939 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel costarred Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman as Jody’s parents. The film was one of MGM’s biggest hits, and Jarman received a Juvenile Academy Award for his performance—one of only 12 child actors to receive the honor before it was discontinued in 1960. A star was born. Under contract to MGM, Jarman was educated in the studio’s schoolhouse alongside classmates Elizabeth Taylor, Margaret O’Brien and Jane Powell. Over the next decade, he appeared in 11 films, including The Sun Comes Up (1949), a Lassie adventure that marked Jeanette MacDonald’s final big screen role; Intruder in the Dust (1949), based on William Faulkner’s novel about a Black man falsely accused of murder; and Rio Grande (1950), in which he played the Civil War soldier son of John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara.

In an interview with The San Francisco Chronicle, Jarman said Intruder in the Dust was his favorite because it anticipated To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) in “dealing with a subject ahead of its time.” Rio Grande, he added, was the most fun to make—he even won over notoriously stern director John Ford. Jarman was the last surviving participant from an iconic group photo of nearly 60 MGM stars, including Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Katharine Hepburn and Judy Garland, taken in honor of the studio’s 25th anniversary. He left Hollywood in the mid-1950s as the studio system declined, and he settled in the Bay Area, where he served as executive director of the San Francisco Film Society (now SFFILM) from 1965 through 1980. In 2018, he published his memoir, “My Life and the Final Days of Hollywood.” He died in January at the age of 90.

Joan Plowright (The Entertainer, 1960)

“Larry would have been so thrilled by all the fuss the Americans are making of me,” Dame Joan Plowright told The Daily Mail in 2004. “Larry” was, of course, Laurence Olivier — her husband of 28 years, who had encouraged her to pursue a Hollywood career. Together, they were a royal couple of stage and screen and among the most esteemed actors of their generation. It was only after Olivier’s death in 1989 that Plowright achieved late-career stardom, earning an Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe win for Enchanted April (1991), as well as another Golden Globe for the HBO miniseries Stalin (1992) in which she played Joseph Stalin’s mother-in-law. She went on to lend her inimitable touch of class to such films as Dennis the Menace (1993), 101 Dalmatians (1996), Avalon (1990), I Love You to Death (1990) and Tea with Mussolini (1999). She also appeared as herself — alongside Dames Judi Dench, Eileen Atkins and Maggie Smith — in the delightful documentary Tea with the Dames (2018). At one point, the others confess to Plowright that acting opposite Olivier had terrified them even more than the critics. Plowright responded that it could be a “bit of a nightmare” for her, too: “Knowing that those who don't really go for you are gonna say, ‘Well, of course, it’s her husband who put her up in it.’ That was my sort of burden.”

Both Olivier and Plowright were married to others when they met — she to actor Roger Gage, he to Vivien Leigh. Olivier first visited her backstage to congratulate her on her star-making turn in “The Country Wife.” Two years later, they co-starred in Tony Richardson’s The Entertainer, with Plowright as the loving daughter of a washed-up song-and-dance man — roles they later reprised in the film version that TCM is airing in tribute. They married in 1961 after both had divorced, and that same year Plowright triumphed on Broadway in “A Taste of Honey,” earning the Tony Award for Best Actress. She later scaled back her own career to focus on raising their family, allowing Olivier to continue his stage and film work. Plowright retired from acting in 2014 after gradually losing her eyesight. In a 1993 interview, Charlie Rose remarked that life seemed to be going beautifully for her — a flourishing screen career, plans to return to the stage and all her children involved in the theater. “It’s a kind of bonus time,” she reflected. “I keep my fingers crossed that it will last a bit.” Plowright died at 95 years old in January.

Lalo Schifrin (Cool Hand Luke, 1967)

Selecting just one film to represent composer Lalo Schifrin may seem like—wait for it—an impossible mission, but as The New York Times noted in its review, Schifrin’s score for Cool Hand Luke “is perhaps the best he has done for films.” Schifrin himself called it his favorite. The score, which combined country and roots music with symphonic elements, was nominated for an Academy Award—one of six nominations he received. He received an honorary Oscar in 2018. In a career that spanned seven decades and hundreds of film and television scores, the Argentinian-born Schifrin composed for nearly every genre: horror (The Amityville Horror, 1979), action (Dirty Harry, 1971), comedy (Bringing Down the House, 2003), family (Sparky’s Magic Piano, 1987), martial arts (Enter the Dragon, 1973), Western (Joe Kidd 1972) and sci-fi (THX-1138, 1971). As The Washington Post observed, he provided the jazz-infused music of “rebellious cool” for Paul Newman, Steve McQueen and Clint Eastwood. “I like to work like a painter,” Schifrin told the National Jazz Archive, “mixing colors and different kinds of sounds.”

Schifrin was equally prolific in television. “Let’s say you have to send a message to your family,” he told SoundTrackFest. “Film music would be an extensive letter where you can say many things, and the equivalent of television would be a telegram, where you have to say the most important things but with fewer words.” He is perhaps best known for his iconic theme for the TV series “Mission: Impossible.” In an episode of “Fun for All Ages,” a podcast for pop culture obsessives, Oscar-winning composer Michael Giacchino recalled reaching out to Schifrin when he signed on to score Mission: Impossible III (2006). He invited Schifrin to lunch and asked if there was anything he should or should not do when adapting his theme. Schifrin’s response: “Just have fun with it.”