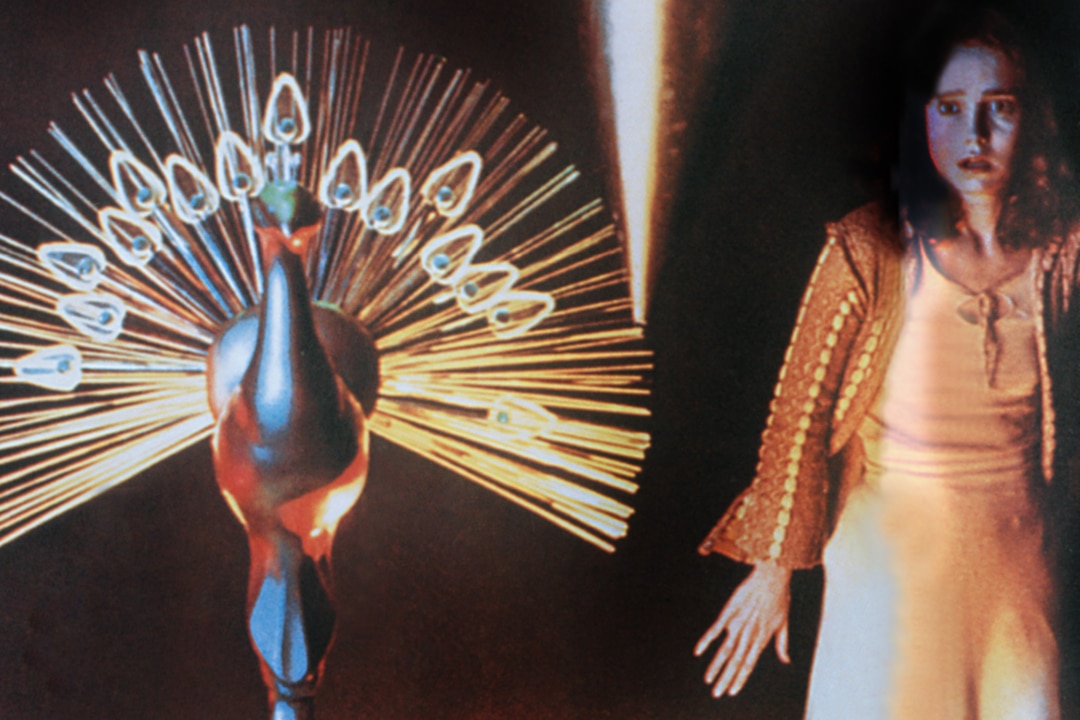

American dance student Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) arrives at Freiburg, Germany's fabled Tanzakadaemie, and is immediately plunged into horror. Her fellow students are going missing, the school's blind pianist is savagely mauled by his own dog...and late at night, an anonymous group of strange people sneak off to a room that doesn't exist to meet a woman who was burned to death many years ago. Drugged, manipulated and marked for death, Suzy has one rough night ahead of her.

Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977) is, to paraphrase Spinal Tap's (1984) Marty DiBergi, Italy's loudest horror film in part because it’s a blood-drenched full sensory overload with a lingering afterburn.

Argento was already a celebrity filmmaker in Italy, notorious for outrageously staged murder scenes. In such films as The Bird with Crystal Plumage (1970) and Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971), Argento had reveled in style for its own effect, but these were no ordinary mysteries. Argento's thrillers deliberately withhold key evidence from the viewer and defy rational explanation. Their plots are frameworks on which the director builds his justly celebrated suspense sequences, which often remain more vivid in the memory than any aspect of the narrative. These aren’t "whodunnits," so much as "lookits!"

With Suspiria, Argento and his co-writer-cum-girlfriend Daria Nicolodi liberated themselves from these restraints. If the villains are witches, whose methods are by definition supernatural, then anything goes. Argento's macabre imagination was let loose, and he was free to indulge his wildest visionary fantasies without restraint. Illogic became a virtue, not a weakness, and Suspiria became the biggest Italian horror film of all.

It begins like any Gothic fairy tale: an unwary American traveler arrives in Germany for an appointment, not knowing that her appointment is with the supernatural. The locals, justifiably superstitious, balk at delivering the traveler to her destination. Argento has dressed these familiar scenes in modern garb—Suzy arrives by airplane on a dark and stormy night, and has trouble hailing a cab to the Dance Academy where she is to train—but we might as well be talking about Jonathan Harker trying to get a carriage to take him to Castle Dracula.

The narrator (speaking in Argento's own voice in the Italian original) carefully establishes Suzy's name, her reasons for travel, even the details of her flight. But these facts, so specific, so precise, are irrelevant. In Suspiria, what we think we can comfortably take for granted will prove to be elusive and deceptive. The trappings of airports and taxis seem to suggest our modern world, but the actual depiction of these things on screen clearly hails from some alternate dimension, a nightmare made flesh.

During this memorable opening sequence, we have so far been shown exactly nothing of any discernible dramatic value, yet the soundtrack has been thundering at full volume while the intensely colored and tightly composed images all seem to suggest the final moments of some epic story, as if we've joined the tale at the fiery climax. "Pay attention," the film shouts, and so we try.

But pay attention to what? No sooner has Suzy been introduced than she is abandoned, and the film abruptly switches focus. The camera swoops after a frightened wretch as she flees through the Black Forest (paging Little Red Riding Hood!), and the viewer is left with a conundrum: we know Suzy's name, her mission, her itinerary-but what use is that if we're going to focus on someone else instead, unnamed, headed in the opposite direction, for reasons unknown? And then, she dies! You could say she's killed by Dario Argento himself. Not only are those the director's own hands seen strangling her in close-up, but her character is killed by filmic technique more than by any actual murderer. The poor girl is murdered by montage, the victim of a homicidal mise-en-scene.

The dizzying changes in narrative perspective throughout the opening sequence disorient the viewer as thoroughly as poor Suzy herself. Arguably, the most nightmare-like of the nightmarish visions served up in the film concerns the death of Suzy's friend Sara, played by Stefania Casini. But there is gore aplenty in Suspiria: necks are cut, limbs are hacked, hearts are stabbed. Argento fetishizes physical violence in ways that signaled a permanent break from the tamer traditions of Gothic horror and inaugurated a new focus on visceral terror that dominates the genre to this day. Yet, for all this, Suspiria's principal inspiration was children's fairy tales. Daria Nicolodi studied “Alice in Wonderland” as she wrote the script, while Argento took his cinematographer to see Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937) as pre-production research.

Snow White's imagery is seeded throughout the film in strange, unexpected ways. This is no mere homage. Consider Madame Blanc, headmistress of the Academy, whose name means "White" but whose moral status remains dubious until the finale. It is no accident that the role of Madame Blanc went to Hollywood legend Joan Bennett. She was, of course, Fritz Lang's favorite leading lady, and Lang's films often revolve around characters whose role as victims or villains is uncertain. The Lang connection in Argento's films is little remarked upon, partly because the press has been too busy ferreting out Hitchcock connections. Argento had cast ex-Lang actors at least as often as he has ex-Hitchcock ones, and while Argento's suspense sequences are modeled on Hitchcock's, they occur within a Langian universe of corruption and deception.

Bennett's best role for Fritz Lang had been in Secret Beyond the Door (1948), a psychological thriller set inside a nightmarish dream-world. Argento pays tribute to Secret Beyond the Door with a few direct filmic quotations throughout Suspiria. Suzy Bannion’s name shares a kinship with one of Fritz Lang's best and most memorable characters, Detective Dave Bannion from The Big Heat (1953). Both Suzy and Dave penetrate, expose and ultimately destroy a massive evil conspiracy. And that is what, at heart, Elena Marcos' coven of witches really is: a criminal conspiracy by a small cabal of villains who exploit their special abilities in secret to amass personal wealth. The fact that one group uses magical powers while the other employs bribes and blackmail is just a difference in detail.

There is, in Lang's work, a prime example of a criminal conspiracy that invoked supernatural or nearly supernatural powers to maintain itself. This was the world of master criminal Doctor Mabuse, a deathless spirit of evil whose powers of mind control enabled him to manipulate world events to his own advantage. Doctor Milius describes witches to Suzy as "malefic, negative and destructive—their knowledge of the art of the occult gives them tremendous powers. They can change the course of events and people's lives, but only to do harm. Their goal is to accumulate great personal wealth but that can only be achieved by injury to others." This could just as easily be a description of Doctor Mabuse. When the blind pianist Daniel first comes onscreen led by his massive seeing-eye wolfhound, it is hard for fans of Lang's Mabuse not to think of the blind clairvoyant Cornelius from The 1,000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). The Dance Academy, like Mabuse's Hotel Luxor from The 1000 Eyes, is the focal point of the villain's power, a work of evil architecture used to spy on and manipulate its victims.

Like Lang's Mabuse films, the equation of criminality with fascism is an unambiguous theme in Suspiria. Dario, auspiciously born in 1940 as Mussolini was deposed, has lived his life in the shadow of a not-distant-enough fascist past, and knows as well as any artist of his generation the difference between fictional monsters and the real deal. Back when the Nazis were first establishing their toehold in German politics, anxious German filmmakers cranked out wild visions of the fantastique in fearful response—movies like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922), which used the outsized stylings of German Expressionism to express a terror beyond words. Suspiria is a modernized work of Italian Expressionism, which takes the landscapes of Caligari and slathers them with lurid colors and a screaming rock score.

The irony is, this film depends so heavily on its characters detecting the faintest, subtlest clues: a snippet of a conversation in the middle of a thunderstorm, the snoring of a person next door, the sounds of footfalls of people sneaking around on the floor below. Yet these tiny sounds are obscured by the avant-garde soundtrack by Goblin. Obscure Greek folk instruments meet wailing voices and African tribal rhythms, not to merely accompany the images but to enhance them. The soundtrack is as much a part of the story as the "then this happened" progression of the plot.

Goblin (oddly billed as "The Goblins" in the opening titles) was an experimental music group that had collaborated with Argento previously. In fact, Argento had a hand in forming the combo, having helped form the group in 1975, when he united a quartet of conservatory-trained musicians to write a score for his thriller Deep Red (1975). Argento would develop melodies on the piano, which the Goblins, led by keyboardist Claudio Simonetti, fleshed out into thumping, ear-shattering music. On Suspiria, a simple 14-note theme in 6/8 time forms the basis of the entire score, carrying hints of a children's nursery rhyme.

The surface attributes of Suspiria are so brash and modern, their noisy bombast can sometimes distract attention from the film's roots in traditional Gothic folklore. Witchcraft was a subject that films often had trouble taking seriously, and an even harder time handling in a modern setting. Part of Argento's brilliance was in recognizing that there was no need to surround his witches with any of the shopworn clichés—no black cats, no pointy hats or bubbling brews, none of the trappings that could so easily invite ridicule.

Suspiria's success and its enduring legacy, which includes a 2018 remake by director Luca Guadagnino, come not simply from its innovative soundtrack or its daring use of graphic violence nor from its audacious rethink of witches and its bold use of color. These maverick touches work because they are built atop a solid foundation of the traditional. Argento and his collaborators began with the familiar—children's fairy tales and Gothic horror conventions, real-world historical horror, animated cartoons and German Expressionism—and managed to make the old seem new. More than 40 years have passed, and Suspiria still shocks and surprises. It remains Italy's loudest horror film because it demands to be heard.

Producer: Claudio Argento

Director: Dario Argento

Screenplay: Dario Argento and Daria Nicolodi

Art Direction: Giuseppe Bassan

Cinematography: Luciano Tovoli

Film Editing: Franco Fraticelli

Original Music: Goblin

Cast: Jessica Harper (Suzy Bannion), Stefania Casini (Sara), Joan Bennett (Madame Blanc), Alida Valli (Miss Tanner), Udo Kier (Frank Mandel), Flavio Bucci (Daniel).

C-98m.

SOURCES:

Interview with Dario Argento and Daria Nicolodi, Fangoria Issue 35, 1984.

"Dario Argento: An Eye For Horror" documentary by Charles Preece and Janne Schack

Dennis Daniel and Michael Will, "Profondo Rosso: Interview with Dario Argento," Psychotronic Magazine, Issue 18, 1994.

Travis Crawford, Liner notes to DVD release from Blue Underground.

Scott Michael Bosco, Interview with Jessica Harper, from the liner notes to DVD release from Blue Underground, conducted 2000.

"Suspiria 25th Anniversary" documentary, Blue Underground.

Tim Lucas, "Suspiria review," Video Watchdog Issue 46.

Linda Schulte-Sasse, "The 'Mother' of all Horror Movies," Kinoeye Volume 2, Issue 11.