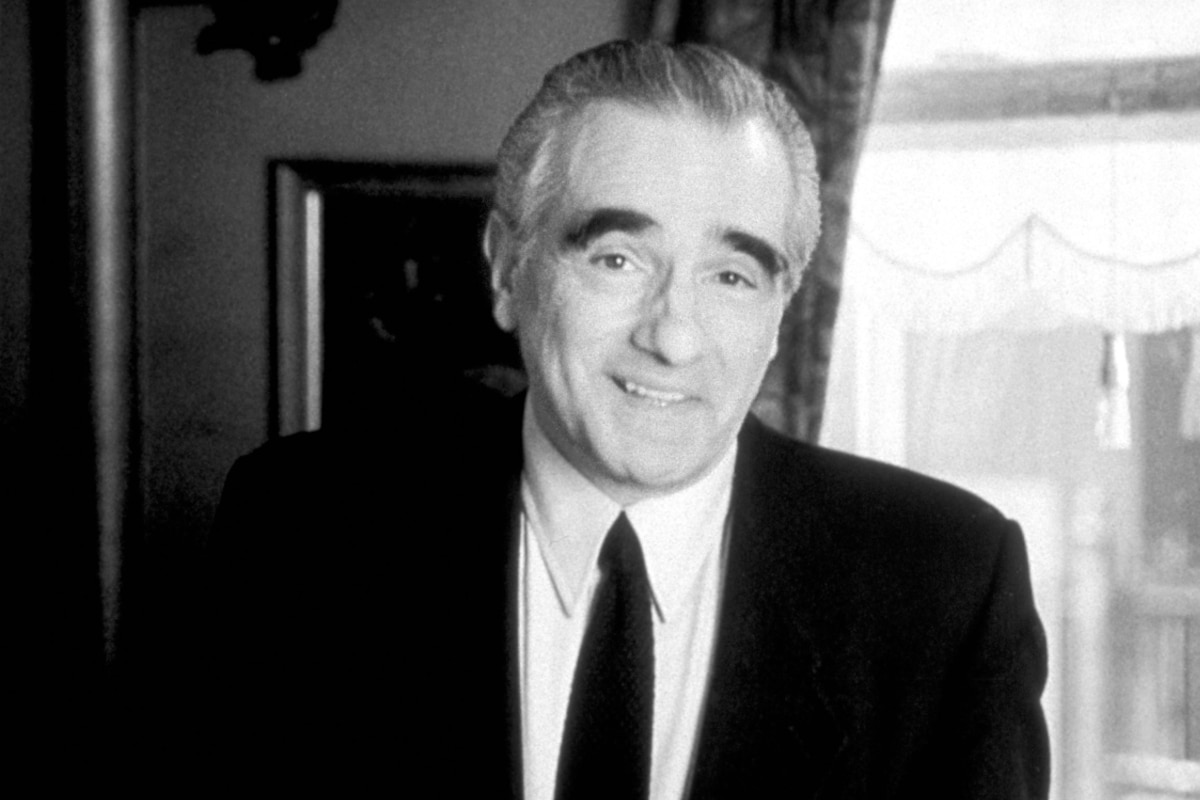

Arguably one of the greatest directors to ever work in and out of Hollywood, Martin Scorsese has made some of the most daring and memorable films of all time. His impressive body of work–which spanned several decades from the mid-1960s on–was a meditation on the visceral nature of violence and male relationships that, more often than not, reflected his own personal angst growing up in the violent streets of Manhattan's Lower East Side under the cloud of a strict Italian Catholic upbringing. Starting with Mean Streets (1973), a gritty look at life on the streets in Little Italy, Scorsese made his mark upon Hollywood, while at the same time discarding many of its traditional conventions. With his seminal films Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980), Scorsese firmly established himself as a top director of his generation. In the 1980s, he excelled with films like After Hours (1985), The Color of Money (1986) and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). He returned to top form with the hyperkinetic mob tale, Goodfellas (1990), widely considered by fans to be among his best films. With each passing film–Casino (1995), Gangs of New York (2002), The Aviator (2004)–Scorsese cemented his legendary status, but failed to win the recognition of his peers. Five times nominated for Best Director, he won an Academy Award in 2007 for his exceptional Irish gangster thriller, The Departed (2006), giving him the recognition he deserved.

Born November 17, 1942 in Flushing, NY, Scorsese grew up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in Little Italy. Both his parents, Catherine and Charles, worked in New York's famous Garment District, which afforded them a life lived in tenements, surrounded by winos and vagrants, some of whom left an indelible impression upon Scorsese for the rest of his life. He suffered from asthma which kept him indoors while the other neighborhood kids played stickball or ran through the gushing water of an opened fire hydrant. To make their son feel better, his parents took him to the movies, unwittingly fostering what would become a lifelong obsession. When he was eight, he began sketching elaborate shot-by-shot retellings of movies he had seen in the theater. By the time he reached 12, the sketches became originals; often titled "Directed and Produced by Martin Scorsese." An outsider to most because of his asthma, Scorsese nonetheless took part in the coming-of-age rituals for kids growing up in a rough-and-tumble neighborhood–namely helping set up kids for a beating, since he could not partake in the fisticuffs himself. Also present throughout his youth was the Catholic Church, which led him to initially aspire to be a priest. He attended seminary during his adolescence, but discovering girls brought to light other possibilities on how to go about life.

After leaving seminary, Scorsese attended Cardinal Hayes High School in The Bronx, before attending New York University, where he earned his bachelor's in English. As an undergrad, he directed his first short film, “What's a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This?” (1963), a nine-minute short about an obsessive compulsive writer (Zeph Michaels) who becomes so fixated on a photograph of a man in a boat that he can concentrate on nothing else. After directing a second short, “It's Not Just You, Murray!” (1964), Scorsese graduated with his bachelor's, quickly moving into NYU's master's program for filmmaking in 1966. He made another short, “The Big Shave” (1967), which depicted a man shaving his hair and the skin on his head, creating a bloody mess in the bathroom, evidence of Scorsese's unflinching use of violence to underscore a deeper truth– in this case, self-mutilation as a metaphor for the increasingly-destructive Vietnam War. With three short films under his belt, Scorsese was ready to take the next bigger step.

While pursuing his master's, Scorsese made his directorial debut with Who's That Knocking at My Door (1967), starring a baby-faced Harvey Keitel as working-class Italian-American from Little Italy who starts dating an educated, uptown girl (Zina Bethune), only to learn she is not a virgin, which clashes with his Catholic upbringing. First developed as a short, then filmed on and off for four years, Who's That Knocking displayed many of the elements that would eventually become Scorsese trademarks–fluid camera movements, a pulsating soundtrack and a visceral portrayal of violence. Despite its showing at the 1967 Chicago Film Festival, the film waited another two years for a theatrical release. Meanwhile, Scorsese began teaching at NYU, where he helped fellow student, Michael Wadleigh, as an assistant director and editing supervisor on Woodstock (1969), which went on to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary. In 1971, Scorsese moved to Los Angeles, CA, where he took a work-for-hire gig with Roger Corman, directing the Depression-era crime thriller, Boxcar Bertha (1972)–all in order to gain more professional experience. Upon seeing a rough cut of the film, friend John Cassavetes chided the young director for "making a piece of shit" and pushed him to do something personal.

Scorsese took Cassavetes' words to heart, going to work on what would become his breakthrough film, Mean Streets (1973), a gritty, semi-autobiographical tale that marked the first of many landmark collaborations with actor Robert De Niro. Scorsese returned to the rough-and-tumble neighborhood of Little Italy, where he explored the struggles of a young hood (Keitel) who tries to save the neck of his hotheaded best friend (De Niro) from the wrath of a local loan shark, while at the same time, struggling to reconcile his Catholic guilt triggered by his reckless lifestyle. Though shot in Los Angeles, Mean Streets brilliantly conveyed the teeming violence and despair of Manhattan's Lower East Side, as well as turning De Niro and Keitel into overnight stars. Meanwhile, Scorsese put on full, dynamic display many of the conventions he only hinted at in his previous work, especially the kinetic pool hall fight scene set to the tune of The Marvelettes' "Please Mr. Postman" that became the first of many of Scorsese's landmark cinematic moments. After a showing at the New York Film Festival, Mean Streets was released to wide critical acclaim, earning a spot on The New York Times' list for "Ten Best Films" in 1973.

He followed up with what ultimately became his only female-centric film, Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974), a bittersweet tale about a Southwest housewife (Ellen Burstyn) who goes on the road to fulfill her dream of being a lounge singer after her husband's sudden death, only to flee her new, abusive boyfriend (Keitel) and take a job as a waitress at a diner ran by a loudmouth cook (Vic Tayback). His first bone fide studio movie, Alice wound up becoming a critical and box-office success that netted Burstyn an Oscar for Best Actress and spawned a long-running CBS sitcom. Scorsese was on much more familiar ground with the testosterone-laden Taxi Driver (1976). An iconographic street opera penned by Paul Schrader, the film marked Scorsese's second collaboration with De Niro, who delivered a tour-de-force performance as Travis Bickle, a lone New York City cab driver whose revulsion towards the scumbags on the streets leads him to try to save a teenage prostitute (Jodie Foster) from her pimp (Keitel), unleashing holy hell along the way. While the film garnered a share of controversy for its bloody finale–a sustained, hallucinatory, brilliantly-staged set piece–Taxi Driver went on to earn four Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture, and eventually went down in cinema history as one of the more iconic films of Hollywood's second Golden Age.

Firmly established as one of the top directors of his generation–which included friends Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas–Scorsese was hailed for being a great practitioner of experimental films, despite working within the studio system. Since he was also a renowned film historian, it was only natural for him to want to make an old-school Hollywood movie. With his next film, New York, New York (1977), Scorsese tried to create a nostalgic look at the movie musical, but shifted gears during filming to shape the story around the deteriorating relationship between a jazz saxophonist (De Niro) and a big band singer (Liza Minnelli, in a performance loosely based on her own mother, Judy Garland). Scorsese returned to documentary filmmaking with The Last Waltz (1978)–a film hailed as one of the finest rock concert movies of all time. Filmed in 1976, the documentary showcased The Band's farewell performance at San Francisco's Winterland Arena, bringing audiences both behind the scenes and upfront for a close look at an exceptional concert highlighted by guest performances by Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, Joni Mitchell and many others.

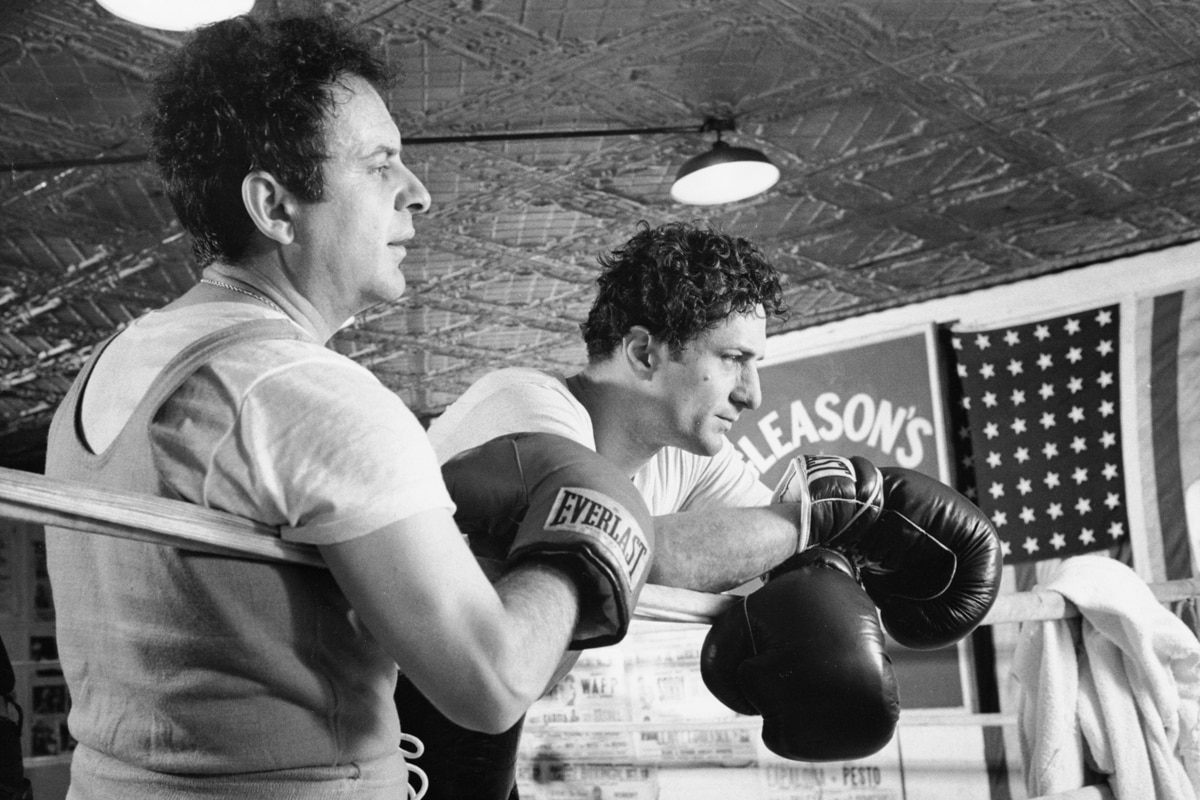

Scorsese went on to direct what many considered his masterpiece, Raging Bull (1980). A searing and unyielding look in black & white at former middleweight boxer Jake LaMotta, who–after becoming the 1948 champ–loses everything due to his self-destructive, violent nature, Raging Bull was later regarded as one of the top movies ever made of any decade. Scorsese was passed over at the Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture, despite De Niro winning a much-deserved Oscar for Best Actor. It would not be the last time Scorsese would go home empty-handed.

For his next film, Scorsese examined the effects of fame in the underrated The King of Comedy (1983), which cast De Niro as Rupert Pupkin, a wannabe stand-up comic living in his mother's basement who becomes so desperate for a break, he hatches a plan to kidnap a famous late-night talk show host (Jerry Lewis) in order to get a spot on his show. The King of Comedy proved to be Scorsese's third financial flop in a row; something that would have shaken the mettle of most other directors, but not Scorsese. He next attempted to make his dream project, The Last Temptation of Christ, but Paramount withdrew funding at the last minute due to a ballooning budget and outrage from Evangelicals. In reaction, Scorsese made After Hours (1985), a cheaply made dark comedy set in Manhattan about a slightly nerdy yuppie (Griffin Dunne) who goes on a bizarre one-night adventure with a Soho woman (Rosanna Arquette) he meets at a café. He moved on to Chicago for The Color of Money (1986)–a sequel to The Hustler (1961)–with Paul Newman reprising his role of pool shark 'Fast' Eddie Felsen and Tom Cruise as his protégé. The Color of Money earned wide critical praise and the first and only Oscar win for Newman.

Returning to his childhood dream of making a movie about Jesus, Scorsese finally made The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), an adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis' novel. Much to the dismay of religious groups once again up in arms, the film depicted a very human spiritual leader (Willem Dafoe) who was a social outcast, wavering between good and evil while battling the desires of the flesh and ultimately choosing a path to redemption. It was the culmination of Scorsese's filmic theses. Clearly an intensely personal project for Scorsese and writer Paul Schrader, the film generated controversy, with religious forces accusing Scorsese of blasphemy and causing some theater and video chains to refuse to carry the film. Scorsese next joined forces with two other famous New York filmmakers, Woody Allen and Francis Ford Coppola, for New York Stories (1989), which showcased three separate films that reflected various aspects of life in the Big Apple. Life Lessons, a drama about an indulgent artist who can not bear to tell his lover (Rosanna Arquette) how he really feels about her art, was often considered the best of the three.

His long-awaited and most-welcomed reunion with Robert De Niro in Goodfellas in 1990 shot his career back up in the stratosphere. In what many felt was the director's best work, Scorsese adapted Nicholas Pileggi's novel, “Wiseguys,” about small-time gangster-turned-Federal witness Henry Hill (Ray Liotta). As a young, half-Irish kid, Hill is taken under the wing of Jimmy Conway (De Niro), a mid-level mobster who shows him the gangster life. Along with a hot-tempered Sicilian (Joe Pesci) quick to pull the trigger, the three embark on a decades-long spree of robbing and killing that eventually leads to a breakdown of their once strictly-held moral code to each other and their bosses. The film captures both the undeniable excitement– as well as the tawdry–details of life on the fringes of the Mafia, pushing audience manipulation to the extreme by juxtaposing moments of graphic violence with dark humor. The film also boasted superb camerawork, including several extended tracking shots, a vibrating soundtrack and sterling performances. While some critics ranked Goodfellas among Scorsese's finest achievements, others were put off by the film's violent excesses.

Scorsese followed up with Cape Fear (1991), a slick remake of the 1962 original that starred Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. Cape Fear turned out to be a significant box office hit. His next film, The Age of Innocence (1993), a Victorian romance based on Edith Wharton's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, seemed an unlikely direction for Scorsese to take. A subtle drama of manners set among the high society of 19th-century New York, Scorsese used a careening camera, sumptuous color and decor to tell the story of an aristocratic lawyer (Daniel Day-Lewis) struggling with his passion for the beautiful cousin (Michelle Pfeiffer) of his fiancée (Winona Ryder). For inspiration, Scorsese turned to such masters as James Whale, William Wyler, Max Ophuls and Luchino Visconti, helping The Age of Innocence earn respectful reviews and healthy box-office totals.

The 1990s saw Scorsese back in typical fashion with Casino (1995), his eighth collaboration with De Niro and focusing on the mafia in the 1970s and 1980s; Kundun (1997), a spiritually focused movie with the Dalai Lama at its core; and the Nicolas Cage psychotropic drama Bringing Out the Dead (1999). Returning to documentaries, he made My Voyages to Italy (2001), a look at the history of the Italian cinema that deeply influenced his style and career. Meanwhile, Scorsese spent a few years working on the epic The Gangs of New York (2002), a sweeping look at the New York immigrant riots of the late 19th century. Starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-Lewis and Cameron Diaz, Gangs went through a series of setbacks, budget problems and delays that resulted from haggling between Scorsese and Miramax head Harvey Weinstein over various details. Upon its release, Gangs was hailed as a mighty achievement, lavishly staged and photographed and featuring a powerhouse performance from Day-Lewis as the delightfully savage Bill the Butcher. Scorsese took home a Golden Globe and earned his fourth Best Director Academy Award nod.

Defying the hype surrounding the difficulties of bringing Gangs to the screen, Scorsese reunited with DiCaprio for The Aviator (2004), a lavish biopic of the legendary billionaire Howard Hughes, which DiCaprio first developed with screenwriter John Logan and director Michael Mann. The Aviator won the Golden Globe award for Best Motion Picture - Drama. It also led the pack with 11 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director, Scorsese's fifth nod in the directing category. In 2006, Scorsese made a triumphant return to form with his next film, The Departed, a slick crime thriller loosely based on the excellent Hong Kong actioner, Infernal Affairs (2002). The Departed earned huge helpings of critical kudos prior to its early October 2006 release, positioning the film for a strong opening weekend. The film did have a substantial box-office take (over $120 million all told), while earning the director another win at the Golden Globe Awards for Best Director - Motion Picture, setting the stage for an Oscar nomination for Best Director at the 79th Annual Academy Awards. To the delight of everyone in attendance and those watching at home, Scorsese finally won the coveted Oscar for Best Director, an honor made that much sweeter when he received a standing ovation and was handed the award by his longtime friends and peers, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas.

In 2007, he formed the World Cinema Foundation, a not-for-profit organization dedicated to preserving neglected films for posterity and restoring others that had been damaged by the ravages of time and poor storage. Aside from his place in the pantheon of filmmakers, Scorsese was a deeply knowledgeable and astute film historian, having long been a champion of film preservation and an ardent foe of colorizing classic black-and-white movies.

After a rare television crossover to direct “No Direction Home: Bob Dylan” (PBS, 2005-06), his Emmy-winning look at Dylan's influential early years spanning 1961-66, Scorsese gathered 18 cameras and shot the footage for what eventually became Shine a Light (2008). Echoing his extraordinary achievement with The Last Waltz, Scorsese spent two nights filming the Rolling Stones at the legendary Beacon Theater in New York in the fall of 2006. Scorsese’s continued success includes Hugo (2011); his reunion with De Niro for The Irishman (2019); his further collaborations with DiCaprio for Shutter Island (2009), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and Killers of the Flower Moon (2024), for which earned the director his 10th Oscar nomination for Best Director and 16th nomination overall.