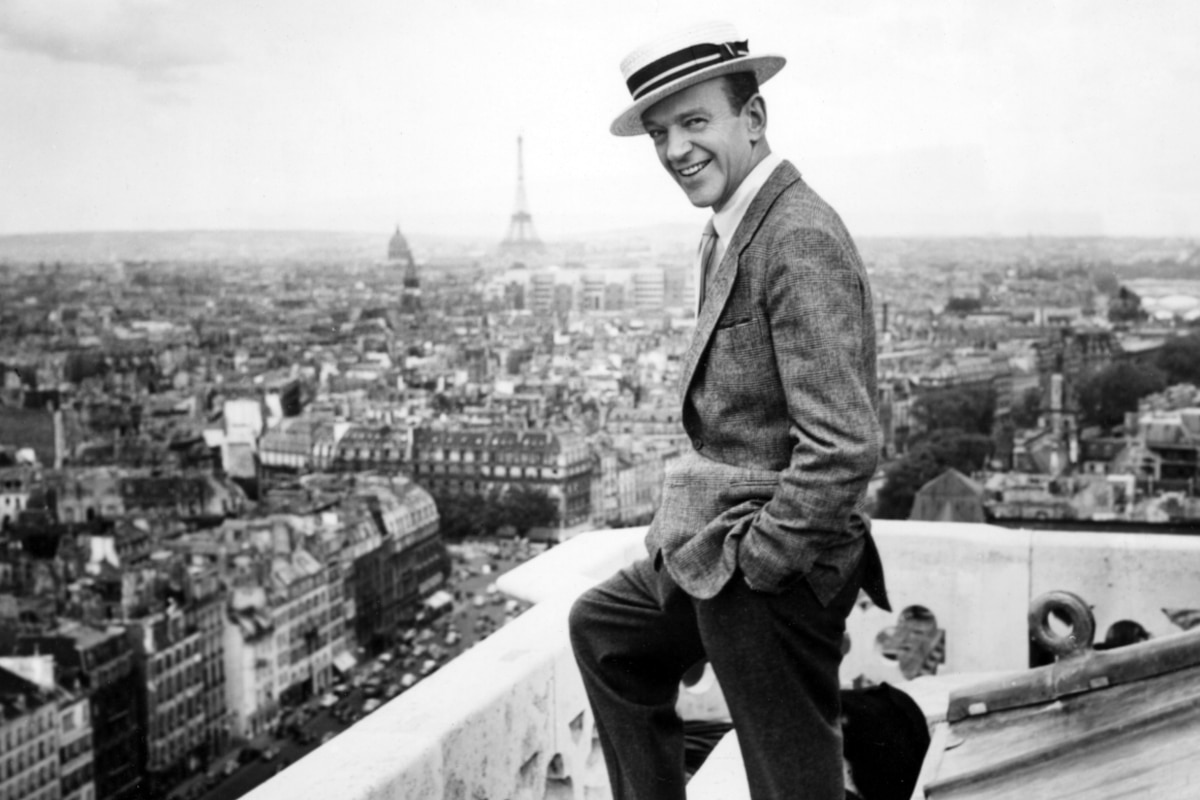

In his book “Hollywood Genres,” Thomas Schatz writes, "The world of any musical film is not so much an actual place as it is the aural and visual rendition of an attitude–and Fred Astaire embodied that attitude. He made us believe that the world is a wondrous and romantic realm imbued with musical rhythm and grace." It is impossible to credit any one artist with revolutionizing the American musical. But if any actor personifies the grace and sophistication of song and dance onscreen, it is Fred Astaire. His film career spanned half a century and he held center stage in some of the most timeless and inventive musical films ever made.

It is difficult to believe that this embodiment of sophistication, floating across glossy Art Deco sets and crooning the best of Cole Porter or George and Ira Gershwin, could have come from a humble background, but he did. He was born Frederic Austerlitz on May 10, 1899, in Omaha, Nebraska, but Omaha did not hold him long. At age seven, he began dancing professionally, touring the vaudeville circuits with his sister Adele as a partner. By the time their teenage years were drawing to a close, Fred and Adele were stars of the Broadway stage, showcased in a series of musicals including “The Passing Show of 1918” and the Gershwins' “For Goodness Sake” in 1922, which was retitled “Stop Flirting!” and given a wildly popular London run a year later.

The siblings' transatlantic popularity continued with another Gershwin musical in 1924, “Lady Be Good” and “The Band Wagon” in 1931 by Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz. The Astaires might have remained a strictly theatrical sensation had Adele not fallen in love with and married Lord Charles Cavendish in 1932, effectively dissolving the brother/sister act. Following suit, Fred began a romance of his own, with Phyllis Potter, whom he would marry in 1933, just as his career was taking a fateful turn. Two days after their wedding (with only a one-night honeymoon in between), Fred and Phyllis departed for Hollywood, where the acclaimed dance man was exploring opportunities on the screen.

They may not have known this at the time, but the Astaires' stage act disbanded at a crucial moment in film history. With the rise of sound, Hollywood studios were recruiting Broadway talent to help them harness the potential of the talking picture. "All Singing! All Dancing!" was a popular boast of many a newly-wired movie theatre, and Astaire had already proven himself a master of both.

In one of film history's more amusing footnotes, one studio executive failed to recognize Astaire's big-screen potential. After viewing a 1933 screen test, the anonymous scout reported to RKO studio head David O. Selznick, "Can't act. Slightly bald. Also dances." The unenthusiastic assessment of Astaire's talents was not heeded by Selznick, who signed the popular song-and-dance man to a lucrative contract. Astaire's first major part was a supporting role in a Clark Gable/Joan Crawford vehicle, Dancing Lady (1933), but it was his second film, Flying Down to Rio (1933), that catapulted him to movie stardom. Thereafter, Astaire was not only given star billing but was allowed complete creative control over the dance numbers.

At the time, musical numbers usually fell into two aesthetic categories. Some directors attempted to mimic the theatrical experience by pulling back to an extreme wide angle and filling the stage with an army of chorines. Others, notably Busby Berkeley, let the camera do the dancing, and sent it zooming overhead, underwater and through the legs of sequined models in geometric displays on revolving stages.

Astaire proposed something simple, yet brilliant: keep the camera close enough to see the actors' faces, yet wide enough to include their entire bodies and never lose sight of them as they whirl and glide across the floor. Nothing could be concealed within the unblinking gaze of the camera; therefore, only the most talented, experienced and graceful performer could carry such a scene. Astaire not only held the attention of the moviegoer, he made the intricate dances seem almost effortless. Modern musicals rely heavily on editing and other visual pyrotechnics to inject energy into the dance numbers, which reflects not only a trend in contemporary cinematic style, but also indicates a shortage of dancers with the absolute skill and photogenic grace of an Astaire.

It was in Rio that Astaire met Ginger Rogers, and their screen chemistry was immediately apparent. They became the epitome of the sophisticated dance team–they were Depression-era escapism at its most sublime. The Astaire-Rogers musicals, including Roberta (1935), Follow the Fleet (1936), Shall We Dance? (1937) and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939) are often credited with having saved RKO studios from bankruptcy during hard economic times.

His films were not always box-office bonanzas, but Astaire, who maintained a vow never to repeat himself, had gained a sterling reputation for innovating fresh approaches to cinematic dance. This earned him the respect of the greatest talents in American music, who eagerly provided him with music for his films: Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields (Swing Time, 1936), Irving Berlin (Carefree, 1938), Cole Porter (Broadway Melody of 1940, 1940), Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen (The Sky's the Limit, 1943) and the Gershwins (A Damsel in Distress, 1937).

Upon arriving at MGM in 1940, Vincente Minnelli, who would become one of the genre's most inventive directors, offered an assessment of the Hollywood musical. "The Fred Astaire dance numbers were the only bright spots in musicals of the late 1930s."

In the 1940s, America moved away from the Depression into a new era, and Astaire, true to his vow of creativity, likewise carried his art into new directions. He made numerous personal appearances in the Hollywood Bond Cavalcade to promote the war effort, including a six-week European tour. He began experimenting with departures from conventional dance, such as "Let's Say It With Firecrackers," in the 1942 film Holiday Inn. In his pursuit of unconventional partners, he also shared the screen with funhouse mirrors, a mop, golf clubs, dumbbells and a hat rack.

After Blue Skies (1946), Astaire intended to retire from the screen to explore other options, including the opening of his own chain of dance studios. But by 1947, he was back before the cameras, starring in Easter Parade (1948), taking the place of Gene Kelly, who had broken his ankle during production. Working at MGM in the 1940s and '50s united Astaire with producer Arthur Freed and directors Minnelli and Stanley Donen, who were redefining the American musical in the Technicolor Era. Among Astaire's most memorable moments from this period was the oft-imitated "You're All the World To Me" number from Donen's Royal Wedding (1951), in which he dances up the walls and across the ceiling of a room (actually a specially constructed rotating set). "The Girl Hunt Ballet," a campy gangster pastiche in Minnelli's The Band Wagon (1953), proved equally influential, inspiring the edgy choreography of Bob Fosse and, by extension, the 2002 hit musical Chicago.

After 1954, the year in which his wife Phyllis died, Astaire began to slow the pace of his dance. Owing less to age than an ambition to broaden his professional horizons, Astaire began appearing in fewer roles, but roles of a wider variety, including a straight dramatic performance in Stanley Kramer's On the Beach (1959). He conquered television, establishing his own production company (Ava Productions) and starring in the musical variety special "An Evening With Fred Astaire" (1958), which won an astounding nine Emmy Awards. In one of his more offbeat appearances, an animated puppet was cast in his image for Rankin-Bass's perennial TV favorite “Santa Claus Is Comin' To Town” (1970).

In his final decades, Astaire accepted eclectic roles, not out of necessity but a sense of fun, appearing in such diverse projects as The Towering Inferno (1974), The Amazing Dobermans (1976), TV's Battlestar Galactica(1978), and Ghost Story (1981), which teamed him with Hollywood veterans Melvyn Douglas, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and John Houseman.

A lifelong aficionado of horse racing, Astaire enjoyed visiting the track during his semi-retirement and even married a young jockey, Robyn Smith, in 1980 (a controversial romance since Smith was more than 40 years younger than her suitor). In 1981, Astaire was given the Life Achievement Award by the American Film Institute. In the summer of 1987, Astaire began experiencing respiratory problems. After a ten-day stay in the hospital, he died of pneumonia on June 22.

Stardates: Born May 10, 1899, in Omaha, Nebraska; died 1987.

Star Sign: Taurus

Star Qualities: The fleetest of feet, lighter-than-air presence, guileless sophistication.

Star Definition: "The greatest dancer who ever lived–greater than Nijinsky." - Noel Coward

Galaxy of Characters: Fred Ayres in Flying Down to Rio (1933), Jerry Travers in Top Hat (1935), "Huck" Haines in Roberta (1935), Don Hewes in Easter Parade (1948).