Con man and "promoter" Otis B. Driftwood (Groucho Marx) is trying to woo the wealthy Mrs. Claypool (Maragret Dumont) into investing in an opera company by promising to secure her entry into high society. The stars of the Milan-based company are the vain, mean-spirited Rodolfo (Walter Woolf King) and the sweet, talented Rosa (Kitty Carlisle). Rosa is in love with the tenor Riccardo (Allen Jones), who has been consigned to the chorus by his rival, Rodolfo. Riccardo's agent, Fiorello (Chico Marx), and Rodolfo's put-upon dresser, Tomasso (Harpo Marx), also become involved in Driftwood's scheme, which brings everyone together on an ocean liner bound for New York. Once in the States, Rodolfo has both Driftwood and Rosa fired from the company. They get their revenge, however, by totally devastating the company's production of “Il Trovatore,” kidnapping Rodolfo, and triumphantly substituting Rosa and Riccardo in the leads.

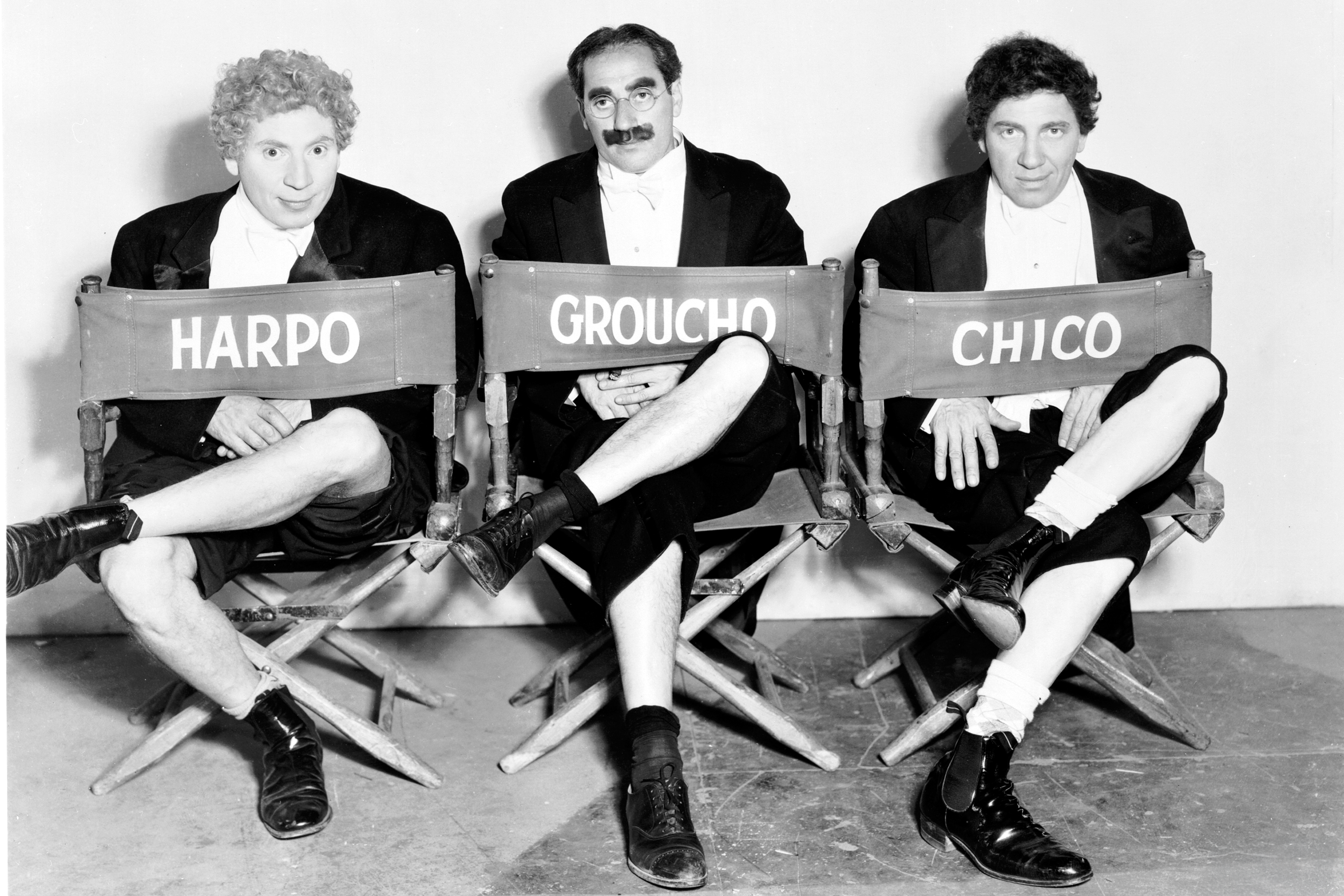

A Night at the Opera was the first Marx Brothers film without Zeppo. Feeling his talent was being wasted playing the bland straight man in their first five movies, he left the group shortly after the debacle of Duck Soup (1933). When Groucho, Harpo and Chico first met with Irving Thalberg to discuss working at MGM, the producer asked if three brothers would cost less than four. "Don't be silly," Groucho shot back. "Without Zeppo we're worth twice as much."

But despite all the games and pranks the Marx Brothers were fond of playing, Kitty Carlisle said the atmosphere on the set was "deadly earnest." She recalled how Groucho would come up to her from time to time, try out a line and ask, "Is this funny?" If she said “no,” he would "go away absolutely crushed and try it out on everyone else in the cast." On the other hand, Chico, she said, was always off in a back room playing cards. And Harpo would work very diligently until about 11 a.m. and then plop himself down on the nearest piece of furniture and begin yelling, "Lunchie! Lunchie!"

The story behind A Night at the Opera is very much the story of its script. Once Thalberg and the Marx Brothers agreed to an approach to the movie, the process of developing the final script was a long one involving many people. The first writer to tackle it was James McGuinness, a former sportswriter and eventual head of the MGM story department, who had penned Tarzan and His Mate (1934). He concocted a plot built around Harpo as the world's greatest tenor, who never sings or speaks throughout the film. Thalberg rejected this idea and, at Groucho's insistence, brought in noted songwriters Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby, who had contributed to the scripts of the Marx Brothers' earlier films Duck Soup (1933) and Horse Feathers (1932) and to their hit play “Animal Crackers,” made into a movie in 1930.

Some sources say Kalmar and Ruby were the creators of the next phase of the story; others credit George Seaton and Robert Pirosh, two relatively unknown writers Groucho considered "unspoiled" neophytes. Whoever it was, the new story was based on an old Broadway legend and popular backstage tale that would cast Groucho as a producer plotting to stage the worst opera in history so that the show would close quickly. The backers he had soaked for ten times the production costs would assume they had lost their money, and Groucho could escape to South America with the sizable profits. But his plans are thwarted when the opera becomes a huge hit and he is left owing ten times what the show actually brings in.

Groucho loved the idea; Thalberg nixed it. He explained they didn't want a funny story but a good, simple plot that the Marx Brothers could use as a springboard for their comic ideas. So the bogus play idea was shelved - and resurfaced more than 30 years later as the Mel Brooks film The Producers (1968). The only remaining elements of Kalmar and Ruby's contribution were the character names of Groucho as Otis B. Driftwood and Margaret Dumont as Mrs. Claypool. As for Seaton and Pirosh, they got their break as the writers of the brothers’ follow-up movie, A Day at the Races (1937).

Finally, the Marx Brothers and Thalberg agreed on established playwrights George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind, two of the creators of the play “Animal Crackers” and the writers of the first Marx Brothers movie The Cocoanuts (1929). When they had finished their draft, Thalberg brought in Jack Benny's top gagman, writer Al Boasberg. He punched up the jokes and wrote the famous stateroom scene, which almost didn't happen thanks to Thalberg's constant pressure on the writer. Tired of repeated calls asking for the material, Boasberg told Thalberg the scene was ready and to come to his office to pick it up. Thalberg and the Marx Brothers arrived to find no Boasberg and no sign of the script. They looked everywhere and were about to give up when Groucho happened to glance up. There he spied the scene, cut into ribbons and nailed to the ceiling. According to Groucho, it took them hours to piece it together.

Later, Thalberg hit on the idea of having Groucho and the boys try the material out in front of live audiences before committing a minute of it to film. The Marx Brothers took five scenes on a road-show tour of Seattle, Salt Lake City, Portland and Santa Barbara. An article in “The Reader's Digest” detailed the process: "When the patrons failed to laugh at a gag, the line came out. When they laughed late, the line was sharpened to take effect more quickly. When they laughed mildly, the line was sent back to the workshop. When they roared, the line was okayed for the film version." Ryskind and Boasberg sat in the audience at every performance (four times a day) making notes and timing audience reactions. Later, when director Sam Wood would try to change the pace or timing of a scene or bit, the writers would remind him that X number of seconds had to be left for laughter. That's why in the film there are what seem to be inexplicable pauses between lines - the performers are holding for the timed response.

While some Marx Brothers fans prefer the earlier Paramount features like Horse Feathers (1932) to the MGM features they made, the majority opinion is that A Night at the Opera is their finest film. Here are some of the most famous Marx Brothers scenes: 15 people crowding into Groucho's tiny shipboard stateroom; Groucho ordering two hardboiled eggs from the ship steward, changing it to three each time Harpo honks his horn; Groucho and Chico agreeing on the terms of Riccardo's contract by tearing away all disputed passages until they're left with only a scrap of paper. And of course, any scene featuring Harpo’s trademark mallet is a crowd-pleaser.

Despite MGM's introduction of a "kinder, gentler" Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera still contains many elements of their trademark zany, anarchic humor: Chico, Harpo and Allen Jones disguising themselves as rather strange and inexplicably bearded aviator heroes to escape the authorities; the brothers eluding a private detective by leading him on a mad chase through a hotel suite whose furniture they keep rearranging; and, of course, Groucho's one-liners, particularly those hurled at Margaret Dumont in what is half-courtship, half-character assassination.

Director: Sam Wood

Producer: Irving G. Thalberg

Screenplay: George S. Kaufman, Morrie Ryskind

Cinematographer: Merritt B. Gerstadt

Editor: William Levanway

Art Director: Cedric Gibbons

Original Music: Herbert Stothart

Cast: Groucho Marx (Otis B. Driftwood), Chico Marx (Fiorello), Harpo Marx (Tomasso), Mrs. Claypool (Margaret Dumont), Rosa (Kitty Carlisle), Riccardo (Allen Jones), Rodolfo (Walter Woolf King).

BW-92m. Closed captioning. Descriptive Video.