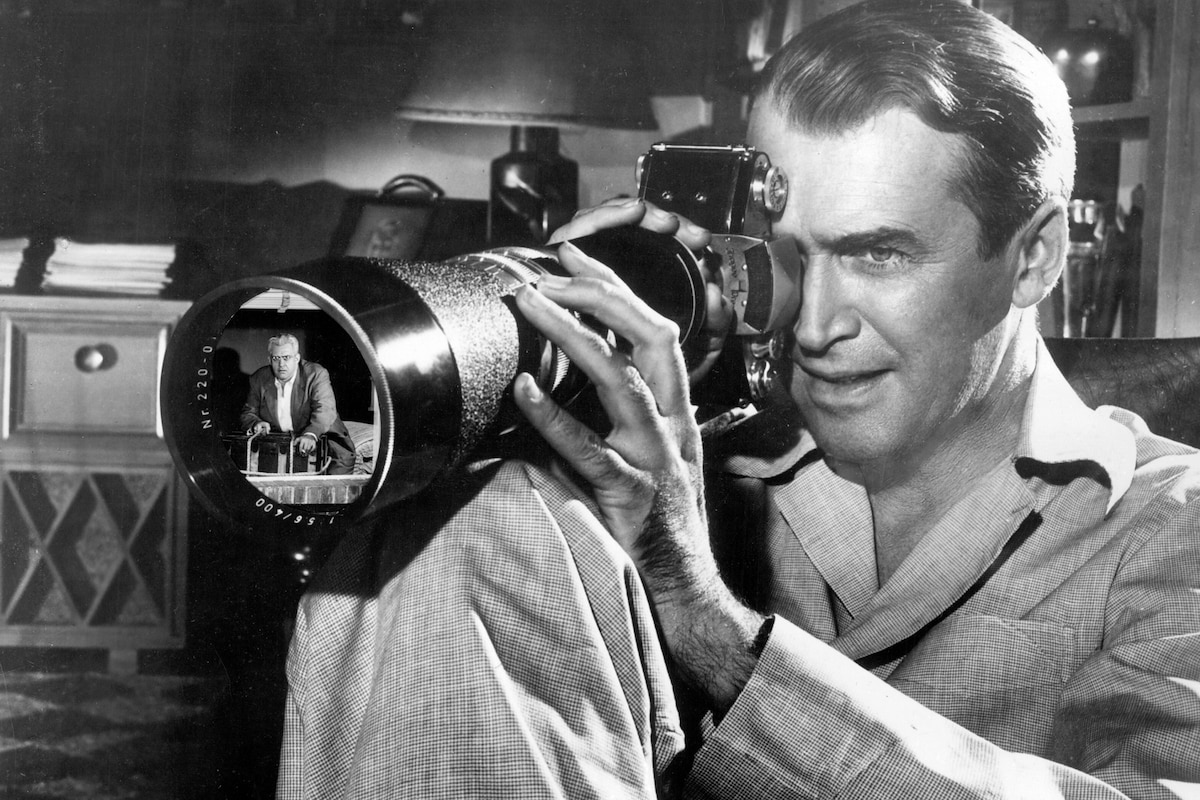

In Rear Window (1954), one of director Alfred Hitchcock's greatest achievements, James Stewart plays L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies, a worldly news photographer using a wheelchair in his apartment after suffering a broken leg. It's a sweltering summer in Greenwich Village, and to pass the time, he takes to spying on his neighbors across the courtyard. In the course of his spying, Jeff begins to suspect his neighbor (Raymond Burr) of murdering his wife. Naturally, police detective Thomas Doyle (Wendell Corey) doesn't believe him, so Jeff and his model girlfriend, Lisa (Grace Kelly), try to prove it on their own. Along the way, Jeff watches the other inhabitants of the building play out their own little stories full of humor, drama and tragedy.

Hitchcock later said of making this picture, "I was feeling very creative at the time. The batteries were well charged." Any scene of the movie proves this point. Take the opening: within seconds after the credits, we know who Jeff is, what he does for a living and why he is confined to a cast and a wheelchair, all without a word of dialogue. It's extremely economical visual storytelling, and the great beauty of Rear Window is that you can notice such techniques while still simply being entertained. The film is so overflowing with suspense, romance and comedy that it looks like it was the easiest, most effortless movie to make. Hitchcock knew that audiences love to work at piecing things together visually, to understand relationships through editing, staging or camera movement, and that is why Rear Window is so captivating.

The subjective point of view of audience-watching-Stewart-watch-neighbors was actually embodied in the original 1942 Cornell Woolrich story, It Had to be Murder, on which the screenplay was based. But Woolrich's yarn contained only the murder storyline. There was no model girlfriend, no hard-nosed lovable housekeeper (Thelma Ritter), no policeman or other neighbors. Hitchcock wanted to expand the story and laid out his ideas to writer John Michael Hayes. He also asked Hayes to spend some time with Grace Kelly, at the time working on Hitchcock's Dial M for Murder (1954), because he wanted her for the new picture. Hayes and Hitchcock both found Kelly's acting in that picture to be stiff – despite the fact that neither man saw any inhibitions in her in real life. So Hayes wrote the part for her, consciously trying to work in her natural charm and outgoing nature.

Kelly recalled in Donald Spoto’s “Alfred Hitchcock: The Dark Side of Genius” that during the filming of Dial M for Murder, "the only reason [Hitchcock] could remain calm was because he was already preparing his next picture, Rear Window. He sat and talked to me about it all the time, even before we had discussed my being in it...He talked to me about the people who would be seen in other apartments opposite the rear window, and their little stories, and how they would emerge as characters and what would be revealed. I could see him thinking all the time, and when he had a moment alone he would go off and discuss the building of the fantastic set. That was his great delight."

A 35-page treatment was good enough for Hitchcock, Stewart and Paramount all to commit to the project, and Hitchcock then left Hayes alone to write the script. The director liked what he read. Hayes remembered that Hitchcock then turned 200 numbered scenes into 600 by inserting all his visualized camera setups. In the interview collection “Hitchcock” by director François Truffaut, the master of suspense admitted, "The killing presented something of a problem, so I used two news stories from the British press. One was the Patrick Mahon case and the other was the case of Dr. Crippen. In the Mahon case, the man killed a girl in a bungalow on the seafront of Southern England. He cut up the body and threw it, piece by piece, out of a train window. But he didn't know what to do with the head, and that's where I got the idea of having them look for the victim's head in Rear Window."

Shooting was done entirely on a soundstage at the Paramount lot. (With few dramatic exceptions, the camera never leaves Stewart's apartment during the movie.) The specially constructed set took 50 men and two months to build, which cost somewhere between $75,000 and $100,000. It was 38 feet wide, 185 feet long and 40 feet high. In order to get the scale right, the soundstage floor had to be removed. Studio art director Henry Bumstead, at the cusp of a distinguished (credits include Vertigo, 1958; To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962; Unforgiven, 1992; and Mystic River, 2003), had the idea for cutting out the floor of the stage so that the basement could function as the courtyard level with Stewart's apartment on the main stage floor. The set "went all the way from the basement to the grids." Sound was recorded live from Stewart's window across the stage in order to achieve a hollow, distanced effect which reinforced the audience's alignment with Stewart. The set included 31 apartments, of which 12 were fully furnished. The whole thing became a marvel that visitors to the studio were eager to see, and it was featured in magazine spreads while shooting was still in progress.

Cinematographer Robert Burks devised a system using a camera with a telephoto lens mounted on a crane to bring the camera close enough to film small details through the windows across the courtyard. Because all but a few scenes are actually shot from inside Jeff's apartment, Hitchcock remained in that part of the set, communicating with his actors across the way via short-wave radio broadcast to their flesh-colored earpieces.

Hitchcock worked closely with Edith Head on the costume designs, being sure to give the more distant characters a very specific look, not only so audiences could always identify them but also to point to their connection with the main characters. For example, Miss Lonelyheart was given emerald green outfits to identify her, and because Lisa later appears in a green suit, Miss Lonelyheart's romantic woes are linked to the story's examination of Lisa and Jeff's problematic relationship. To add more color to the actor’s appearances, Hitchcock had Raymond Burr made up in short curly white hair and glasses, costumed in white button-down shirts and depicted as a heavy smoker – all to evoke Hitchcock's first American producer David O. Selznick, with whom he had a complex and contentious relationship.

Thelma Ritter said Hitchcock never told you if he liked what you did in a scene and if he didn't like it, "he looked like he was going to throw up." Stewart also learned how to read Hitchcock’s expressions. The director and actor had a friendship that was oddly intimate while being somewhat proper and distanced. They rarely socialized outside of work and didn't talk much on the set but communicated in unspoken glances. Stewart said Hitchcock didn't discuss a scene with an actor but preferred to hire people who would know what was expected of them when he said "action." The most Hitchcock would say to Stewart, according to the actor, was something like, "The scene is tired," thereby communicating that the timing was off.

The director liked working with Stewart, especially in comparison to his other most frequent star, Cary Grant, who was described as fussy and demanding. Stewart, in Hitchcock's eyes, was an easy-going, workman-like performer. But Wendell Corey, who appeared with Stewart in several films, said the actor also had a "whopping big ego" and could intimidate even Hitchcock by out-shouting and out-arguing him if he thought a scene wasn't going well. "There was steel under all that mush," Corey said.

By most accounts, everyone was crazy about Grace Kelly. "Everybody just sat around and waited for her to come in the morning, so we could just look at her," Stewart said. "She was kind to everybody, so considerate, just great, and so beautiful." Stewart also praised her instinctive acting ability and her "complete understanding of the way motion picture acting is carried out."

When Rear Window first opened, many critics noted the connection between Stewart's voyeuristic photographer and the moviegoing public. As Hitchcock said to Truffaut in an interview, "He's a real Peeping Tom. In fact, Miss Lejeune, the critic of the ‘London Observer,’ complained about that. She made some comment to the effect that Rear Window was a horrible film because the hero spent all of his time peeping out of the window. What's so horrible about that? Sure, he's a snooper, but aren't we all?" But other significant Hitchcock themes also emerge in the course of the film.

For several years, Rear Window and other key Hitchcock films like Vertigo were withdrawn from distribution by Hitchcock and were unavailable for viewing. However, in 1983, Universal Studios was able to acquire the rights to reissue the films from Hitchcock’s estate. They were restored by Robert Harris and James Katz, who managed to repair and save the negative of Rear Window. It was in terrible shape when they began their work. The yellow color layer had been stripped away due to repeated lacquering, and they spent six months developing a new restoration technique to put the layer back, something that had not been done before.

Producer/Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cinematography: Robert Burks

Film Editing: George Tomasini

Production Design: Hal Pereira, Ray Moyer

Music: Franz Waxman

Sound: Harry Lindgren, John Cope

Cast: James Stewart (L. B. Jeffries), Grace Kelly (Lisa Fremont), Wendell Corey (Detective Thomas J. Doyle), Thelma Ritter (Stella), Raymond Burr (Lars Thorwald), Judith Evelyn (Miss Lonely Hearts).

C-115m. Letterboxed. Closed captioning.