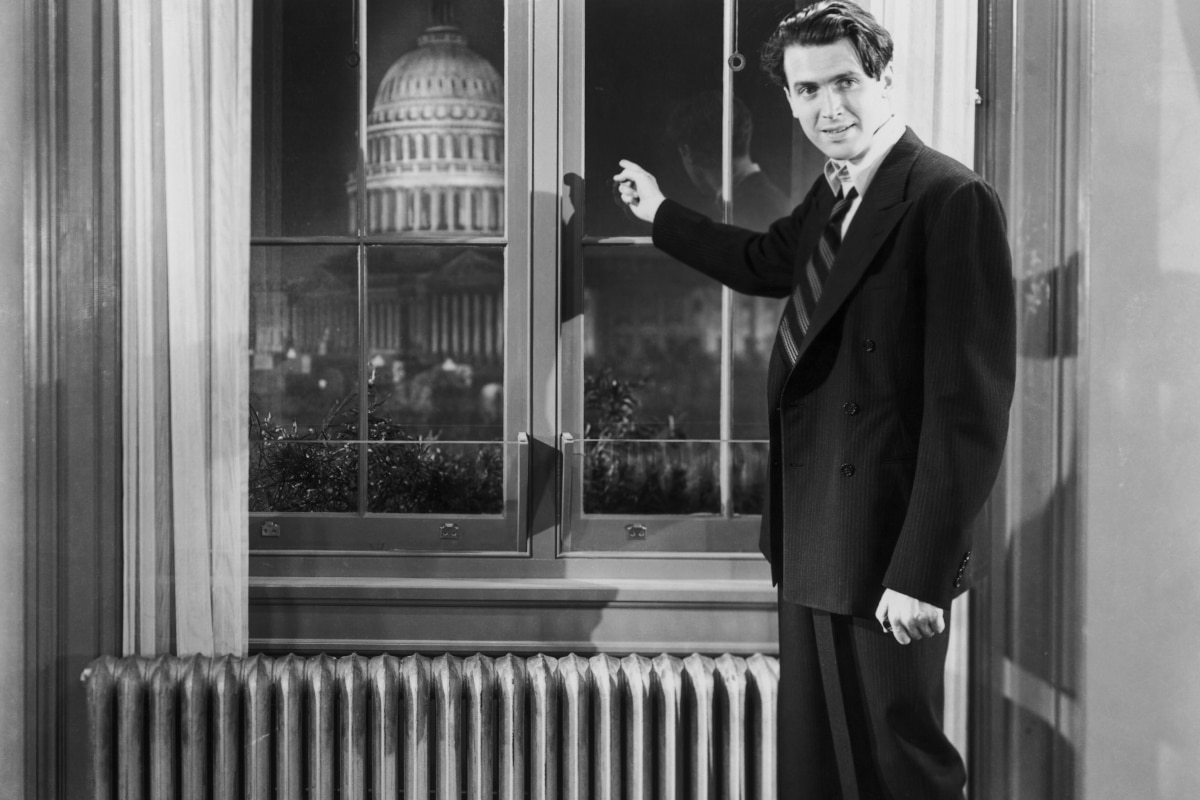

Though it’s now universally revered as an ode to democratic ideals, Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) was originally denounced by many Washington powerbrokers. Jimmy Stewart’s lead performance made him a star and is justly remembered as the key component of a beautifully constructed narrative. But Capra, for all his flag-waving and sometimes naive moralizing, saved a great deal of bite for the hallowed halls of American government.

If not subversive, the movie is at least driven by a strong distaste for the misuse of power by our elected officials. This was an exceptionally gutsy message at a time when Americans were concerned with the rise of Nazism overseas, and Capra surely knew he would ruffle a few feathers. But he put his foot down and said exactly what he wanted to say, much like the film’s patriotic lead character. This is the kind of movie that makes you want to light up a sparkler.

Stewart plays Jefferson Smith, a young man who takes over after the unexpected death of a junior Senator. Smith is despised by his cynical secretary (Jean Arthur) and is quickly portrayed as an appointed yokel by the D.C. press. Undaunted, he tries to introduce a bill that would build a much needed boys’ camp in his state. When a powerful businessman named James Taylor (Edward Arnold) and the state’s senior Senator, Joseph Paine (Claude Raines), discover that the camp will be built on land that Taylor plans to sell for an enormous profit under the provisions of an impending bill, they try to bribe Smith.

Smith, of course, stands his ground, so the two men set about ruining him. This eventually leads to an unforgettable filibuster scene that solidified Stewart’s persona–the first persona of his multi-dimensional career, anyway–as a common man with bottomless reserves of backbone and dignity. (Stewart had a doctor administer dichloride of mercury near his vocal chords to give his voice the exhausted rasp he was looking for at the close of Smith’s filibuster.)

Capra nearly cast Gary Cooper, but finally settled on Stewart. “I knew he would make a hell of a Mr. Smith,” he said. “He looked like the country kid, the idealist. It was very close to him.” Stewart knew this was the role of a lifetime, one that could place him near the top of the Hollywood heap. Jean Arthur later remembered his mood at the time: “He was so serious when he was working on that picture, he used to get up at five o’clock in the morning and drive himself to the studio. He was so terrified something was going to happen to him, he wouldn’t go faster.”

In his delight with the role, Stewart began to attend the rushes – something he had seldom done with his films at MGM. Capra screened the footage at the projection room in his house. As quoted in “Jimmy Stewart: A Life in Film” by Roy Pickard, the actor said, "The first time I stopped off at Capra's house, I was there an hour and 40 minutes. There was take after take, from every angle. He really covered himself. Every scene from every angle. Well, I didn't stay to the end. The next night it was clearly going to be even longer! After an hour I turned to Frank. He was fast asleep." Needless to say, Stewart soon went back to avoiding dailies.

Capra faced a daunting logistical problem in filming the Senate scenes for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. The Senate chamber had been faithfully recreated on the Columbia stages by art director Lionel Banks and a huge team of craftsmen, and the set was just that: a chamber. It was a tall, four-sided set filled with hundreds of people. Action required for the story would also be taking place simultaneously on three levels: the Senate floor, the rostrum where the Vice President sat and the galleries holding the press, the pages and the public. As Capra put it in his autobiography, "How to light, photograph, and record hundreds of scenes on three levels of a deep well, open only at the top, were the logistic nightmares that faced electricians, cameramen and soundmen."

Capra would also rely heavily on reaction shots of the many observers in the scenes set in the Senate chamber. He wanted to retain a natural flow to these shots and so, for these reasons, the usual one-camera set up could not be employed; "...we might still be there," Capra said. The technical team "...devised a multiple-camera, multiple-sound method of shooting which enabled us, in one big equipment move, to film as many as a half-dozen separate scenes before we made another big move."

Capra also described in his autobiography a novel way of keeping continuity in performances during the filming of close-ups. For example, in filming a master shot of a scene between Arthur and fellow actors, the actors can obviously bounce lines off each other in a natural way, but what to do when shooting Arthur's close-up of the same scene? Capra says, "...I 'invented' a way to surround Jean Arthur in her close-up with the exact reality that had surrounded her in the master shot... The sound of the master shot was recorded not only on film, but on a record as well. When the master shot was approved, the sound department rushed the record back to the set and put it on a playback machine. Attached to my chair were a volume-control dial and a push button with which I could cut in or cut out the playback's loudspeaker at will. ...No actors, stand-ins, or script girls mouthing insipid feed lines. Just Jean Arthur and the playback."

Even in the classics-heavy year of 1939, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was a major achievement, arguably the finest picture of Capra’s storied career. It may wrap itself up a bit too easily, but you’d have to have a heart of stone to not be moved by the journey. Or, in lieu of that, you could be a U.S. Senator or Washington newspaper reporter circa 1939. On October 17, 1939, the picture was previewed at Washington’s Constitution Hall. The preview was a major production featuring searchlights and a National Guard band playing patriotic tunes; “The Washington Times-Herald” even put out a special edition covering the event. Four thousand guests attended, 45 Senators among them. About two-thirds of the way through the film, the grumbling began, with people walking out. Some politicians were so enraged by how “they” were being portrayed in the movie, they actually shouted at the screen. At a party afterward, a drunken newspaper editor took a wild swing at Capra for including a drunken reporter as one of the characters!

Several politicians angrily spoke out against the film in newspaper editorials, which, in the long run, may have helped its box office. Sen. Alben W. Barkley viewed the picture as “a grotesque distortion” of the Senate, “as grotesque as anything ever seen! Imagine the Vice President of the United States winking at a pretty girl in the gallery in order to encourage a filibuster!” Barkley, who was lucky he didn’t get quoted on the film’s posters, also said, “...it showed the Senate as the biggest aggregation of nincompoops on record!”

Senator James F. Byrnes of South Carolina suggested that official action be taken against the film’s release...lest we play into the hands of Fascist regimes. And Pete Harrison, the respected editor of “Harrison Reports,” urged Congress to pass a bill allowing theater owners to refuse to show films–like Mr. Smith–that “were not in the best interest of our country.”

Not everyone, especially American moviegoers, saw Capra’s vision as an affront to democracy. Frank S. Nugent, a critic for “The New York Times” wrote, “[Capra] is operating, of course, under the protection of that unwritten clause in the Bill of Rights entitling every voting citizen to at least one free swing at the Senate. Mr. Capra’s swing is from the floor and in the best of humor; if it fails to rock the august body to its heels–from laughter as much as from injured dignity–it won’t be his fault but the Senate’s, and we should really begin to worry about the upper house.”

Not only did Mr. Smith Goes to Washington score a resounding success with critics, it also did well with audiences. The film made millions at the box office, but due to its high production cost (almost $2 million) and distribution expenses, the net profit to Columbia was only $168,500. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was the last obligation Capra had to the studio and Harry Cohn, and following its completion he was a free agent.

Produced/Directed by: Frank Capra

Screenplay: Sidney Buchman

Cinematography: Joseph Walker

Art Direction: Lionel Banks

Editors: Gene Havlick and Al Clark

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Principal Cast: James Stewart (Jefferson Smith), Jean Arthur (Clarissa Saunders), Claude Raines (Sen. Joseph Paine), Edward Arnold (Jim Taylor), Harry Carey (President of the Senate), H.B. Warner (Sen. Fuller), Guy Kibbee (Gov. Hubert Hopper), Thomas Mitchell (Diz Moore), Eugene Pallette (Chick McGann), Beulah Bondi (Ma Smith).

BW-131m. Closed captioning.