Network was financed and distributed by United Artists and MGM, despite the fact that UA had recently settled with Chayefsky in a lawsuit over the company's right to lease his previous film, The Hospital (1971), to ABC-TV in a package with a less successful film. UA originally rejected Network as being too controversial but reconsidered after MGM agreed to make the film. Lumet began a period of rehearsals in early 1976 in a ballroom of the Diplomat Hotel in New York City. Like most Lumet movies, the film was shot in New York, although control-room and news-studio scenes were filmed at CFTO-TV Studios in the Scarborough district of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Lumet said that he planned a very specific visual scheme for the film, shooting the early parts with available light and minimal camera movement, as in a documentary. As the movie progressed, he added more light and movement so that the final sequences were as brightly lighted and "slick" as possible.

Faye Dunaway would later say that this was "the only film I ever did that you didn't touch the script because it was almost as if it were written in verse." She was as happy with director Sidney Lumet as with the writing, describing him as "one of, if not the, most talented and professional men in the world. In the rehearsals, two weeks before shooting he blocks his scenes with his cameraman. Not a minute is wasted while he's shooting and that shows not only on the studio's budget but on the impetus of performance." Dunaway also managed to put aside their earlier clashes and enjoy an apparently cordial relationship with leading man William Holden. She claimed that during the shooting of the new film, "I found him a very sane, lovely man." She later revealed, however, that she had wanted Robert Mitchum as Max.

In researching her role as the rare female in the mostly male world of television executives, Dunaway met with NBC daytime programming vice president Lin Bolen. Bolen noted later that while she could see something of herself in Dunaway's mannerisms and speech patterns, she disavowed any further connection to the character and was appalled by her lack of moral standards. Chayefsky and Lumet made it clear to Dunaway that they wanted a cold-blooded, soulless characterization with no sympathetic shadings. "I know the first thing you're going to ask me," Lumet told her. "Where's her vulnerability? Don't ask it. She has none. If you try to sneak it in, I'll get rid of it in the editing room, so it'll be a wasted effort." Dunaway's then-husband, J. Geils Band frontman Peter Wolf, warned her that she could risk typecasting in such a role, but Dunaway plunged ahead fearlessly.

Holden had some reservations about the scene were he and Dunaway, as Max and Diana, are in bed making love and, in her excitement, she exclaims about the ratings of her successful TV show. At a climactic moment she cries out, "We're getting more publicity out of this than Watergate!" "Such scenes are not to my liking," Holden later said. "I believe lovemaking is a private thing and I don't enjoy depictions of it on the screen." He rationalized that, "If nobody had been in bed on the screen before, I might have hesitated." But he went with it, understanding that "The scene was not meant to be pornographic. It was meant to disclose a character flaw, the fact that Faye talks all the way through it tells more about her. It was Paddy's way of getting the dialogue out." Holden did allow, however, that he felt "the scene was meant to be more amusing than it came off."

Lumet recalled that Chayefsky was usually on the set during filming, and sometimes offered advice about how certain scenes should be played. Lumet allowed that his old friend had the better comic instincts of the two, but when it came to the domestic confrontation between Holden and Straight, the four-times-married director had the upper hand: "Paddy, please, I know more about divorce than you!"

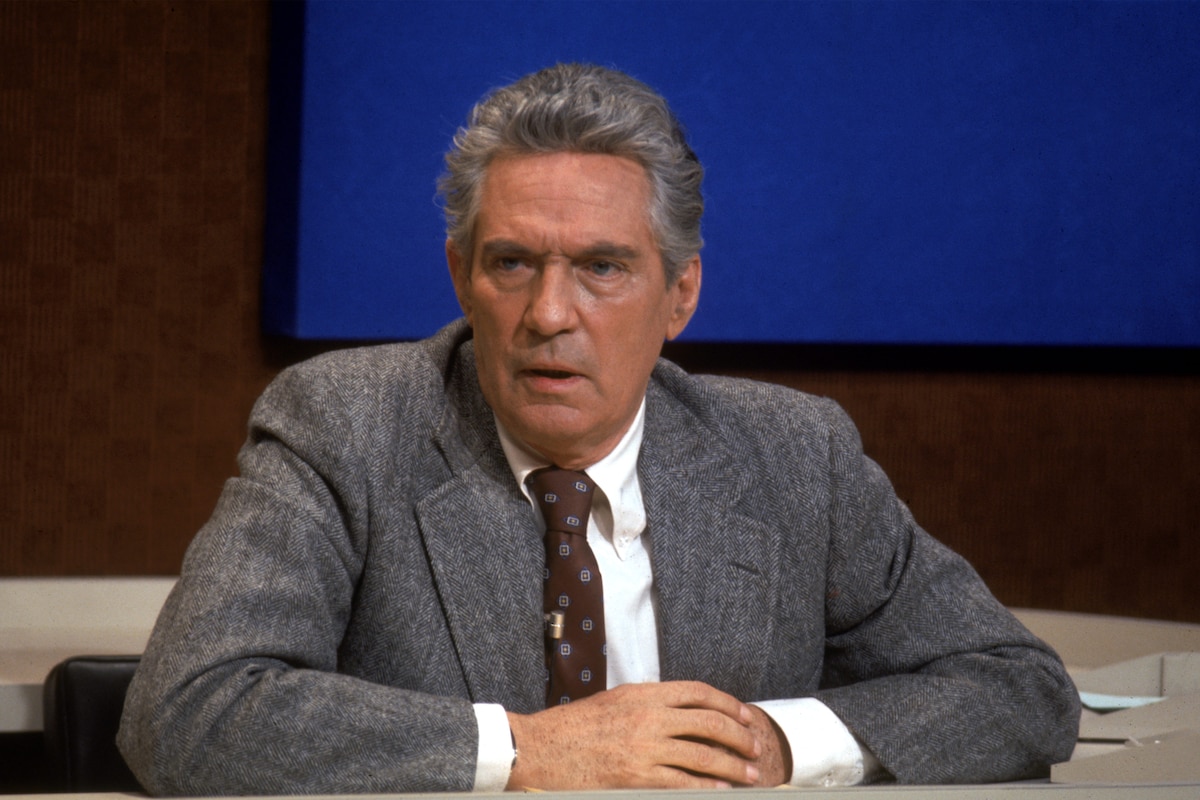

Finch, who had suffered from heart problems for many years, became physically and psychologically exhausted by the demands of playing Howard Beale. By the time he filmed the "mad as hell" scene - the most celebrated of his career - he was able to deliver it only one and a half times. The final performance features the second take for the first half of the speech and the first take for the second half. Finch, who lived just long enough to see the completed film, further pushed himself with a hectic series of appearances to promote it. On January 14, 1977, the night after he had appeared on The Tonight Show, he collapsed in the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel and died of a massive heart attack. He was 60 years old.

Upon its release in November 1976, Network became an instant success with audiences and most critics. Made at a reported cost of $3.8 million, it grossed $23.7 in the U.S. alone.

By Roger Fristoe

Behind the Camera-Network

by Roger Fristoe | March 05, 2014

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM