The germ of the idea for Network came from a real-life incident when television reporter Christine Chubbuck killed herself on live television during a newscast on July 15, 1974, on the Sarasota, Fla., TV station WXLT. She said, "In keeping with Channel 40's policy of bringing you the latest in blood and guts, and in living color, you are going to see another first: attempted suicide." Then she shot herself behind the right ear.

That same year, former television writer Paddy Chayefsky began work on the screenplay for Network. The Bronx-born scenarist, whose brilliant work during TV's Golden Age of the 1950s had led to scripts for feature films, had won Oscars® for his screenplays for Marty (1955) and The Hospital (1971). Disillusioned and annoyed with the path television had taken, Chayefsky began crafting a darkly satirical script about the medium that had once nurtured him but now aroused his scorn.

After his death in 1981, Chayefsky left behind extensive notes on the creation of that script. In those writings, now held by the New York Library for the Performing Arts, he noted that he was seeing the negative attitudes of the era of Watergate and the Vietnam War in all the programming of the broadcast networks, and wanted to address this in his screenplay. In a typewritten note to himself he wrote that Americans "don't want jolly, happy family type shows like Eyewitness News; the American people are angry and want angry shows." Chayefsky described television as "an indestructible and terrifying giant that is stronger than the government," and wrote that "the only joke we have going for us is the idea of ANGER."

In researching his screenplay, Chayefsky took trips to newsrooms in San Francisco and Atlanta, and compiled data on the lives of such national anchors as Walter Cronkite and John Chancellor. After strong reactions to the completed film from members of the media, he would make it clear in letters to prominent broadcasters that he had not been targeting them. He also claimed that he "never meant this film to be an attack on television as an institution in itself, but only as a metaphor for the rest of the times."

For his imaginary network, called UBS, Chayefsky created a fictional corporate hierarchy involving 23 different people and even worked out a detailed programming grid with such grotesque programs as "Death Squad," "Killer Theater" and "Celebrity Checkers." As he developed incidents in the screenplay, he realized that the tone was becoming more and more absurdist: "All this is Strangelove-y as hell. Can we make it work?"

Helping him "make it work" was director Sidney Lumet, who also was intimately acquainted with the world of television. He and Chayefsky were close friends, having both established their careers during the glory days of 1950s TV in New York City. Lumet's directing career, which would span almost 60 years, had included episodes of CBS-TV's You Are There, in which historical events were dramatized as Walter Cronkite "reported" on them. It was one of the first hybrids of news and entertainment that play a prominent role in Network. Lumet's movie career began with 12 Angry Men (1957), which had been originally written for television. He would later say that, in approaching Network, he thought of it not as satire but as "sheer reportage."

In his notes, Chayefsky jotted down his ideas about casting. For the inflamed anchor eventually played by Peter Finch, he envisioned Henry Fonda, Cary Grant, James Stewart and Paul Newman. He went so far as to write Newman, telling him that "You and a very small handful of other actors are the only ones I can think of with the range for this part." Director Lumet wanted Fonda, with whom he had worked several times, but Fonda declined the role, finding it too "hysterical" for his taste. Jimmy Stewart also found the script unsuitable, objecting to the strong language. Early consideration was given to real-life newscasters Walter Cronkite and John Chancellor, but neither was open to the idea. Although not mentioned in Chayefsky's notes, George C. Scott, Glenn Ford and William Holden reportedly also turned down the opportunity to play Beale - although of course Holden ended up playing battle-weary executive Schumacher. For that role Chayefsky had listed Walter Matthau and Gene Hackman. Glenn Ford was under consideration for this part as well, and was said to be one of two final contenders. Holden finally got the edge because of his recent box-office success, The Towering Inferno (1974).

For Faye Dunaway's role as the hard-driving programming exec, Chayefsky thought of Candice Bergen, Ellen Burstyn and Natalie Wood. The studio suggested Jane Fonda, with Jill Clayburgh, Diane Keaton, Marsha Mason and television actress Kay Lenz also in the running. But Lumet wanted Vanessa Redgrave, whom he considered "the greatest English-speaking actress in the world"; Chayefsky, a Jew and supporter of Israel, objected on the basis of Redgrave's support of the Palestinian Liberation Organization. Lumet, also a Jew, reportedly said, "Paddy, that's blacklisting!" to which Chayefsky replied, "Not when a Jew does it to a Gentile!"

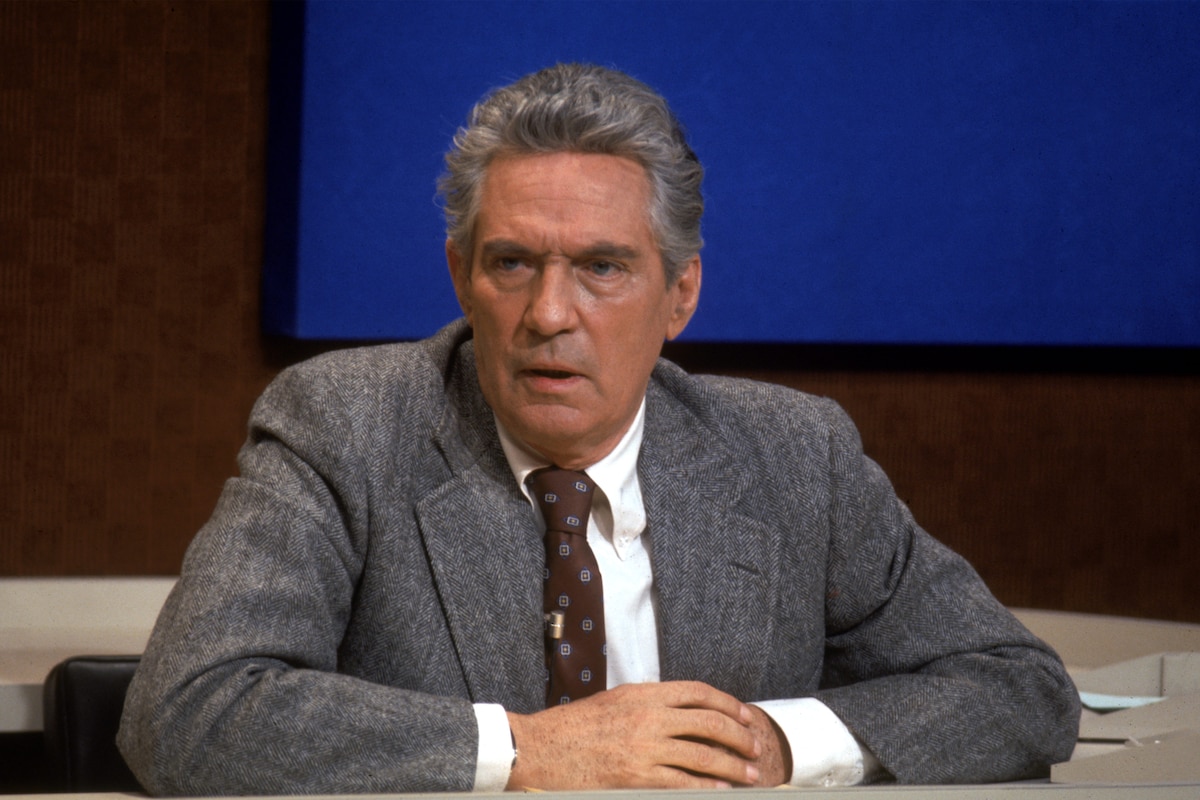

It was Chayefsky who eventually came up with the inspiration of Peter Finch as a possible Beale. The movie's producers were wary that Finch, born in England and raised partly in Australia, would be able to sound like an authentic American; they demanded an audition before his casting could be considered. Finch, an actor of considerable prominence, reportedly responded, "Bugger pride. Put the script in the mail." Immediately realizing that the role was a plum, he even agreed to pay his own fare to New York for a screen test. He prepared for the audition by listening to hours of broadcasts by American newscasters, and by weeks of reading the international editions of The New York Times and the Herald Tribune into a tape recording, then listening to playbacks with a critical ear. Producer Howard Gottfried recalled that Finch "was nervous as hell at that first meeting over lunch and just like a kid auditioning. Once we'd heard him, Sidney Lumet, Paddy and I were ecstatic because we knew it was a hell of a part to cast." Finch cinched the deal with Lumet by playing him the tapes of his newspaper readings.

There was some concern that the combination of Holden and Dunaway might create conflict on the set, since the two had sparred during an earlier co-starring stint in The Towering Inferno. According to Holden biographer Bob Thomas, Holden had been incensed with Dunaway's behavior during the filming of the disaster epic, especially her habit of leaving him fuming on the set while she attended to her hair, makeup and telephone calls. One day, after a two-hour wait, Holden reportedly grabbed his costar by the shoulders, pushed her against a soundstage wall and snapped, "You do that to me once more, and I'll push you through that wall!"

Three outstanding character actors were added to the cast of Network. Robert Duvall, a specialist in terse understatement, took on the role of the bland but villainous president of programming, seen by Duvall himself as "a vicious President Ford." Ned Beatty agreed to play the cynical, garrulous corporate head despite the brevity of the role, which amounts to one long, dynamic monologue. Years later he advised other actors to hesitate about turning down any role because "I worked a day on Network and got an Oscar® nomination for it." Beatrice Straight had an even briefer role as the betrayed wife of Holden's character, with a performance that clocked in at five minutes and 40 seconds. She had won a Tony award in 1953 for playing an anguished wife who is similarly cheated upon in Arthur Miller's The Crucible.

By Roger Fristoe

The Big Idea-Network

by Roger Fristoe | March 05, 2014

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM