Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni had firmly established himself as one of the most interesting filmmakers of the 1960s with a string of fascinating, if sometimes inscrutable, films including L'Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), L'Eclisse (1962) and Red Desert (1964). Antonioni's work usually challenged traditional approaches to narrative, and he quickly became one of the most exciting and influential voices of European cinema.

Soon after the success of these films, Antonioni signed a contract with Italian producer Carlo Ponti which obligated him to a three picture deal. The first film that Antonioni decided to make as part of the contract was Blow-Up.

The initial inspiration for Blow-Up came to Antonioni in the form of Argentinean writer Julio Cortázar's short story "Las babas del diablo" ("The Devil's Drool") in which a translator living in Paris named Michel one day sees a woman with an adolescent boy. Using his camera to take some candid shots of the scene, which appears to be a seduction in progress, the angry woman demands to be given the film. As she is joined by another man who appears to be involved in the situation, the boy runs off. Using the process of blowing up the photograph to take a closer look, he soon realizes that the scene was something more sinister that his picture taking interrupted.

Antonioni was drawn to the story's central idea of using a photographic enlargement to reveal a hidden truth or meaning, and he planned to do a loose adaptation of it drawing from his own imagination.

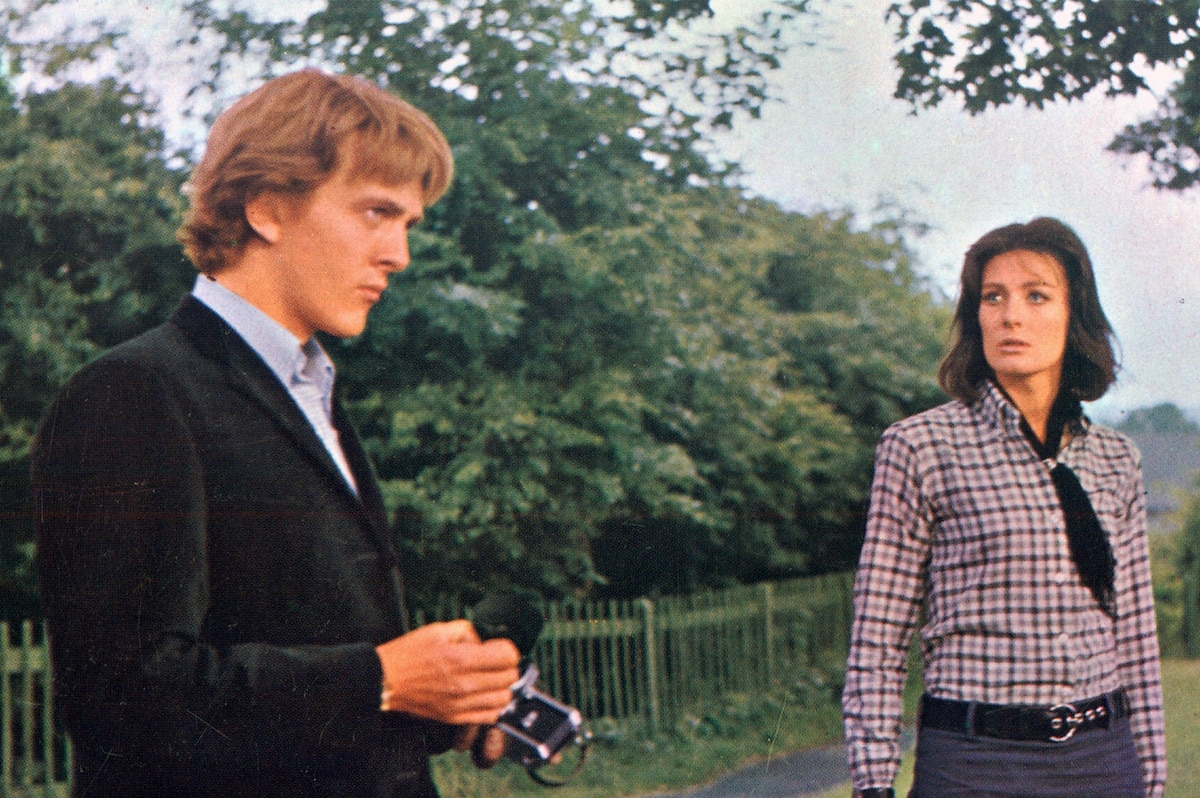

He began constructing the story of a highly successful fashion photographer named Thomas who snaps some photos of a woman in a park embracing an older man who appears to be her lover. When she angrily demands the film back, he is intrigued enough to enlarge the images he took, which soon reveals that he may have just witnessed -- and captured on film -- a murder in progress.

Antonioni gave a great deal of thought to where the setting of the film would be. He felt that because Thomas was a much in-demand high fashion photographer, Blow-Up could easily have been set in New York or Paris. He also considered setting it in Italy, but he realized early on that this would be "impossible" for the story. "A character like Thomas doesn't really exist in our country," he explained. "At the time of the film's narrative, the place where the famous photographers worked was London. Thomas, furthermore, finds himself at the center of a series of events which are more easily associated with life in London, rather than life in Rome or Milan. He has chosen the new mentality that took over in Great Britain with the 1960s revolution in lifestyle, behavior, and morality, above all among the young artists, publicists, stylists, or musicians that were part of the pop movement. Thomas leads a life as regulated as a ceremonial, and it is not by accident that he claims not to know any law other than that of anarchy."

The character of Thomas wasn't the only reason that Antonioni abandoned his usual Italian setting for London. "The risqué aspect of the film," he said, "would have made filming in Italy almost impossible. Italian censorship would never have tolerated some of those images."

The Italian director had already spent time living in London while his longtime paramour and frequent creative muse, the actress Monica Vitti, worked on Joseph Losey's 1966 film Modesty Blaise. He spent time getting to know the city as well as becoming a frequent observer of the fashion and art world, soaking in the details of what would become the glamorous world of Blow-Up.

During his stay in London, Antonioni spent time observing some of the era's most important professional photographers at work to help inform the character of Thomas. Antonioni seemed to be most inspired by his time with high fashion photographers David Bailey and John Cowan, whose kinetic working styles and dynamic personalities helped provide inspiration.

To play the role of Thomas, Antonioni chose actor David Hemmings, whom he discovered performing in a small London stage production. The versatile Hemmings had been working steadily in film, stage and television roles since the 1950s, but had not yet achieved stardom. That would all change with Blow-Up.

When Antonioni met Hemmings backstage after his performance in the play Adventures in the Skin Trade, Hemmings could register no sign of approval with his performance in the director's eyes. "To say that my first meeting with the great director himself was a disappointment would be understating it," said Hemmings in his 2004 autobiography Blow-Up and Other Exaggerations. "As far as I could tell, he didn't react at all to what I'd just done. He took my hand perfunctorily with a doleful shake of his head, as if he'd just slept through the play, showing, as far as I could see, absolutely no interest in my performance, and that was that."

However, the next day, Hemmings got a call that Antonioni wanted to meet with him at the Savoy Hotel in London. Hemmings was incredulous, but intrigued. "After a perfunctory greeting," recalled Hemmings about the meeting, "he studied me and waggled his head from side to side in a gesture of profound negativity. I had been in the room less than five minutes and I was already convinced the interview wasn't going well. After a few moments he confirmed this with another prolonged bout of head shaking, as if rejecting an unacceptable truffle. In a thick Italian accent, he said, 'You looka too younga.'"

"I wasn't going to give in that easily. 'Oh no,' I answered emphatically, 'I can look older. I've done it before. You can trust me on this. I am an actor.' He smiled indulgently; he was a much older hand at this game than me. His halting English gave him the excuse to insert death-defying chasms of silent suspense. He shook his head again. 'How do you look blond?'"

"'Much older,' I replied instantly."

When Antonioni appeared skeptical, Hemmings thought that was the end of the road. "I left the Savoy in the certain knowledge that my encounter with the Maestro had been a total failure and I'd blown a big chance. I took the train back to Elmhurst Court in Croydon in a state of deep depression."

To his great surprise, however, he received a call from producer Carlo Ponti the next day inviting him to do a screen test at the studio of photographer John Cowan in Pottery Lane, which was to be a shooting location for the film. At the test, it seemed to Hemmings that no matter what he did, he could not please Antonioni, who kept shaking his head as if he did not like what he saw. "I was boiling with resentment," said Hemmings. "Why did the bastard ask me here? Could you please just not waggle that chin again!"

As Hemmings tried his best to improvise and find something - anything -- to impress the great director, he could not help feeling that he was blowing his chance. "The director sat unmoving beneath the camera and watched," he said. "Every time I looked at him, his head was still shaking. No, no, it said. Wrong. More unpleasant thoughts crossed my mind. Well, fuck you! I've given you my best shot. I can't do any more...I walked out aching with a massive depression and a badly bruised ego."

Two days later, Hemmings got the phone call that he had won the part. He couldn't believe it. "Everything in his body language said he thought I was crap," he said. "Now he's given me the bloody part."

Hemmings didn't see the script until the first day of his costume fitting for the film. "As soon as I was out of the building," he said, "I dived into the nearest pub...ordered what I've always called a PoG - a pint of Guinness - which I didn't remember drinking, opened the script and buried myself in it. I read it three times from cover to cover before I rang [my girlfriend] Jane and told her. 'What's it like?' she asked eagerly. 'God knows,' I said, shaking my head rather like the Maestro. 'I don't understand what the hell it's about.' All I cared about then was that I had secured one of the most coveted film roles in Britain at the time."

Antonioni found co-star Vanessa Redgrave while she too was performing on the London stage in the title role of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. Redgrave was already an established stage actress and had begun to make a splash in films such as Morgan! and A Man for All Seasons (both 1966). In her 1991 autobiography Redgrave recalled how Antonioni decided that her character Jane should look a little different from her. "Antonioni asked me to dye my hair black and shave an inch from my hairline to give me a higher forehead," she said. Redgrave obliged.

The days leading up to shooting the film were "angst-ridden" for David Hemmings. "Apart from all the usual strain of meeting dozens of new people involved in a production," he said, "at the front of my mind was the fiercely nagging doubt as to whether I could deliver the nebulous character. There seemed, on paper, so little to him; and anyway, the director himself in our acquaintance thus far had demonstrated no faith whatsoever in my abilities - apart, of course, from giving me the role. However, while I longed to get started on the first day's shooting, the week passed in a haze of frantic preparation. The last couple of days were the worst."

Blow-Up would become a complex multilayered film, but Antonioni wanted to remain flexible while he worked and let the film decide for itself what it wanted to be. "...my narratives are documents built not on a suite of coherent ideas," he said in an interview, "but rather on flashes, ideas that come forth every other moment. I refuse, therefore, to speak about the intentions I place in the film that, at one moment, occupies all my time and attention. It is impossible for me to analyze any of my works before the work is completed. I am a creator of films, a man who has certain ideas and who hopes to express them with sincerity and clarity. I am always telling a story. As far as knowing whether it is a story with any correlation to the world we live in, I am always unable to decide before telling it. When I began to think about this film, I often stayed awake at night, thinking and taking notes...But at a certain point, I told myself: let's start making the film--that is to say, let's try, for better or for worse, to tell the story..."

In a 1969 interview Antonioni told Roger Ebert, "I never discuss the plots of my film. I never release a synopsis before I begin shooting. How could I? Until the film is edited, I have no idea myself what it will be about. And perhaps not even then. Perhaps the film will only be a mood, or a statement about a style of life. Perhaps it has no plot at all, in the way you use the word."

by Andrea Passafiume

The Big Idea-Blow-Up

by Andrea Passafiume | March 04, 2014

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM