John Wayne was a busy actor in the 1930s. After taking his first lead in the epic The Big Trail (1930), an ambitious early sound western that became an expensive failure for Fox, the strapping young actor was tried out in college films, sports movies, dramas, and comedies, but it was in westerns and action films where he found the success. He quickly established himself as a reliable young hero in dozens of low budget westerns, most of which ran under an hour. The double feature was coming into popularity and westerns were an inexpensive way to get a second movie on the bill, or even play top of the bill in rural theaters.

Monogram was just the company to supply those films and in 1933 they hired Wayne to an eight-picture deal. Sagebrush Trail (1933) was his second picture for Monogram. His first, Riders of Destiny, was an awkward fit that cast Wayne as a singing cowboy (his singing voice was dubbed for the film), but producer Paul Malvern was impressed with his confidence and charm and liked the way Wayne took instruction and threw himself into action. "Handled himself real well," he noted. "And we had no problems with him."

He quickly put Wayne into Sagebrush Trail as John Brant, aka "Smith," an earnest young man convicted of a murder he didn't commit who breaks prison and goes west to find the real killer. Economy was the watchword of these films, all budgeted between $10,000 and $12,000 and shot in under two weeks (some even less than a week), and Wayne was ready for the challenge. "We didn't worry about nuances in these serials or B pictures," he explained to a Life magazine reporter. "Get the scene on film and get to the next scene." He learned his craft on the job. "[T]hey taught me three things. How to work, how to take orders, and how to get on with the action."

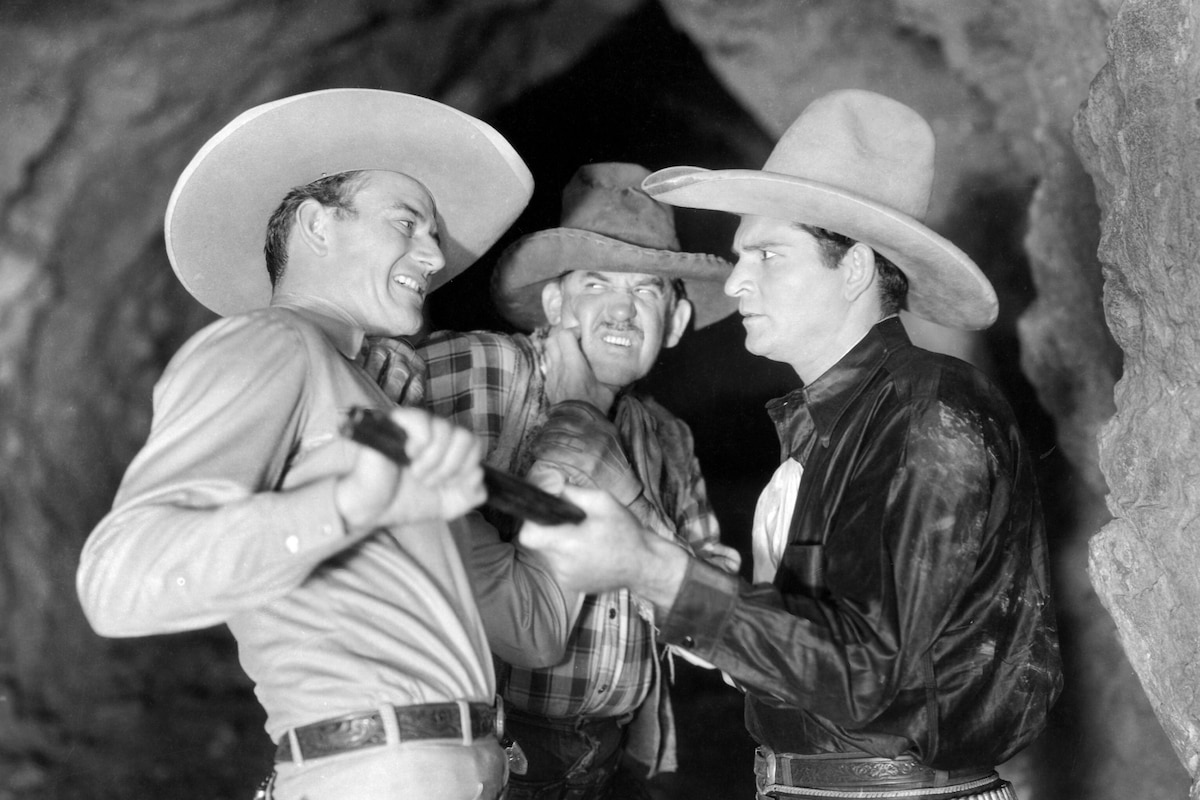

To economize, Sagebrush Trail skips the jailbreak completely and opens Wayne already riding the rails west and escaping into the hills with the local sheriff in hot pursuit. Spotted by another outlaw, an affable fellow who uses the name Bob Jones (Lane Chandler), he's taken in by a local gang of bandits who rob the stages that pass through the town and begins his search. It's a revenge movie, an innocent man drama, a buddy picture, an outlaw western, a sagebrush redemption story, and a romantic triangle, and the dialogue is there just to get us to the action: shoot-outs, hold-ups, racing horses, and a runaway stagecoach, all in under an hour. Director Armand Schaefer makes memorable use of the film's most distinctive location: the hideout in an old mine that runs clear through the hill to the other side. He stages a big shootout around the mouth of the cave and sends the climactic chase right through the tunnel, giving a familiar convention a whole new dynamic.

The great stuntman Yakima Canutt, who taught Wayne how to perform his own stunts and doubled for Wayne in his more dangerous and elaborate action demands (most famously doing the daring drop under the racing coach in Stagecoach, 1939), takes a supporting role as the leader of the outlaw gang. Not much of an actor, he stands out thanks to a prominent scar applied to his right cheek and a rough-and-tumble fistfight early in the film. His more important role in the film was performing the more challenging stunts, notably a novel method of sneaking aboard a moving stagecoach without the drivers ever seeing him. Wayne handled the rest of the action himself, jumping into the saddle and leaping from a moving horse to take down another rider.

By Sean Axmaker

Sources:

John Wayne: American, Randy Roberts and James S. Olson. The Free Press, 1995.

The Young Duke: The Early Life of John Wayne, Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss, Twodot, 2007.

The Complete Films of John Wayne, Mark Ricci, Boris Zmijewsky and Steve Zmijewsky. Citadel, 1990.

Sagebrush Trail

by Sean Axmaker | February 14, 2014

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM