Synopsis: Harriet is a young British girl growing up along a river in Bengal, India, where her father manages a jute press. A budding writer, she observes the world around her and the dynamics of her close-knit family, and experiences her first romantic feelings for Captain John, an American soldier who was wounded in the war. She competes for the young man¿s attentions with Valerie, the wealthy, beautiful and somewhat spoiled daughter of the jute press owner, and Melanie, the Anglo-Indian daughter of Mr. John, the neighbor with whom Captain John is staying. When tragedy suddenly strikes her family, Harriet must also come to terms with the inevitability of death.

Jean Renoir's The River (1951), alongside Michael Powell's Black Narcissus (1943), is the best-known adaptation of the work of Rumer Godden (1907-1998), the noted British writer. Born in Sussex, England, Godden moved with her parents to India and lived in Assam and Bengal before returning to England to complete her studies. During the 1930s she began to publish her first novels, achieving a critical and popular breakthrough with Black Narcissus (1939), the story about an order of nuns' failed attempt to establish a school in the Himalayas. Many critics in retrospect have interpreted that novel as a commentary on the ultimate failure of the British Empire's colonial project in India. During World War II Godden moved back to India but returned to England in 1944, visiting India again in 1950 during the shooting of Renoir's film. The difficulties of her marriage and her wartime experiences in India are recounted in the gripping BBC documentary Rumer Godden: An Indian Affair, which is included on the new Criterion Collection DVD. The author also wrote three autobiographies: Two Under the Indian Sun (1966), A Time to Dance, No Time to Weep (1987) and A House With Four Rooms (1989).

Godden's original 1946 novel The River is a marvelously crafted work. Written in the third person from the perspective of the mature writer that Harriet would eventually become, its terse but expressive language preserves the child's way of seeing the world without sentimentality or condescension. While Harriet and her family clearly occupy the center, the novel is also noteworthy for its impressionistic evocations of the sights, sounds and smells of India. It's one of the better coming-of-age novels I've read, certainly worth the effort to hunt down.

Renoir's film, his first after leaving Hollywood in the late 1940s, was independently produced by Ken McEldowney, an owner of several successful florist shops. It's an odd duck with its mixture of narrative and semi-documentary footage and professional and non-professional actors. It doesn't entirely work due to wooden acting, but the fault lies more with Renoir's direction of actors than with the non-professionals per se. Any supposed awkwardness in Patricia Walters' performance as Harriet can be readily forgiven, for it fits on the whole with the character; even her occasionally breathless line delivery fits with the character as written in the book. The dancer Radha is also undeniably stiff as Melanie, an Ango-Indian character invented for the film. However, compared to them the noted character Arthur Shields, who plays her father Mr. John, is truly annoying with his overly folksy mannerism and nuggets of homespun wisdom. To be fair, much of this has to do with how the Mr. John character is written in Renoir and Godden's screenplay adaptation.

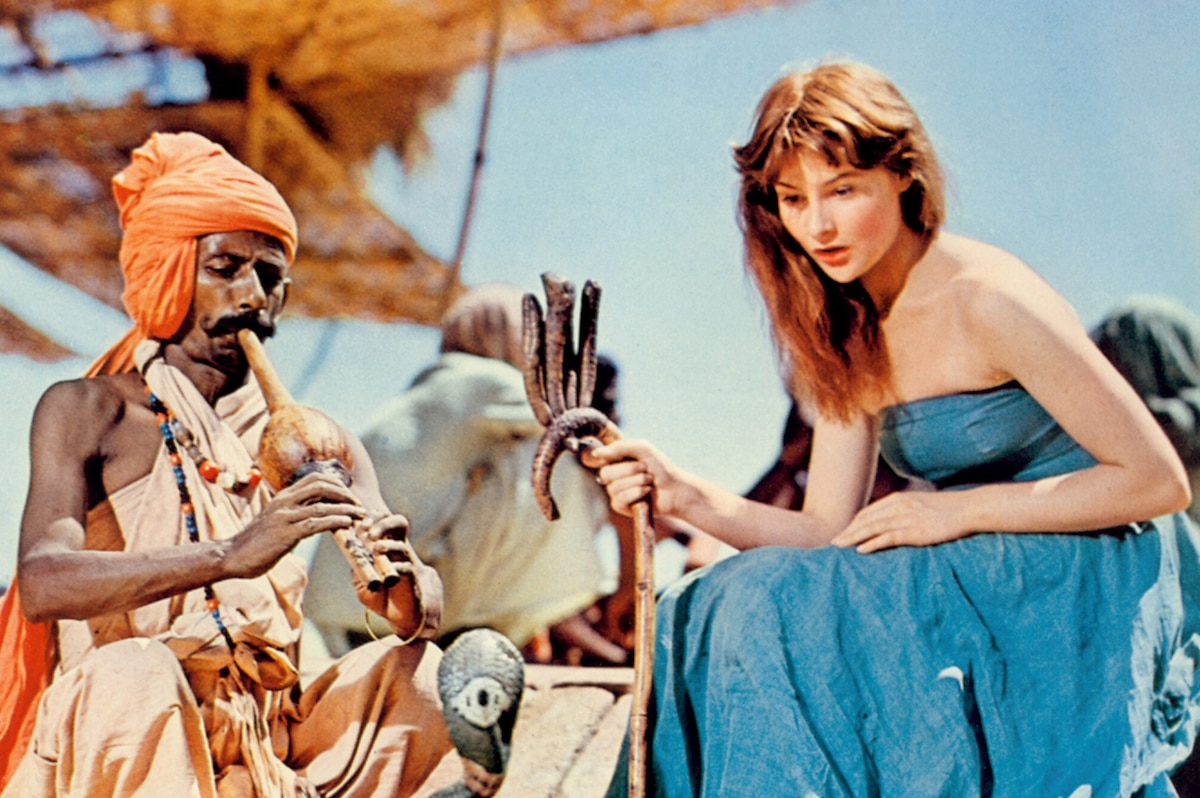

There is a great deal of expository dialogue where the characters explain aspects of Indian culture, to say nothing of exchanges in which they mouth homilies obviously intended to reflect Hindu philosophy. One can certainly understand the desire to introduce a 1950s audience to Indian culture, but it undercuts the purity and force of Godden's original conception. On the other hand, while the extensive semi-documentary scenes depicting Indian work customs, religious rituals and dance dilute the narrative concentration that distinguished the original novel and add a touristic element to Renoir¿s film, thanks to Renoir's painterly eye these scenes are compelling in their own right and even help make up for the shortcomings in the acting. Thus, as with other late Renoir films such as The Golden Coach (1952), one winds up admiring it despite its flaws, and it even repays multiple viewings. Still, it is hardly a match for Renoir's masterpieces of the 1930s.

The real star of the film, what makes one keep coming back to it, is its stunning Technicolor cinematography. Criterion's new high-definition transfer of the film is based on the 2004 restoration of the film conducted by the Academy Film Archive. Simply put, the color and detail are luxuriant. The print exhibits very little of the color fringing, due to misalignment of the three color layers, that you often see on unrestored Technicolor prints. For those interested in the use of color in film, the restoration and transfer alone make the disc a must-purchase. Extras on the disc include: a filmed introduction by Renoir for the film's French release; the aforementioned documentary on Rumer Godden; a video interview with Martin Scorsese, one of the film's most ardent supporters; an audio interview with producer Kenneth McEldowney; a stills gallery; and essays by Ian Christie and Alexander Sesonke in the booklet accompanying the disc.

For more information about The River, visit the Criterion Collection. To order The River, go to

TCM Shopping.

by James Steffen

The River on DVD

by James Steffen | June 16, 2005

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM