"Hitchcock takes you behind the actual headlines to expose the most explosive

spy scandal of the century!"

Tagline for Topaz.

At the time it was released in 1969, Topaz did indeed stir up

controversy among Alfred Hitchcock fans. First of all, many were puzzled as to why

the director wanted to adapt Leon Uris' popular but sprawling novel to the screen

and more importantly, why he failed to inject it with his trademark suspense. Later

critics have pointed to the film as an experiment in light and color that allowed

the classic director to adjust to new filmmaking styles. In this he was greatly

aided by production designer Henry Bumstead, who carried the master's color ideas

out in ingenious designs for a Harlem hotel, a Cuban mansion and two international

airports. But audiences at the time gave the film a big thumbs down, making it

Hitchcock's third flop in a row.

Topaz wasn't even the film he had wanted to make. Still reeling

from the failures of Marnie (1964) and Torn Curtain

(1966), he was more interested in filming a script he had in development that eventually

would become his comeback picture, Frenzy (1972), but nobody

at Universal Pictures was interested. The studio's head, Lew Wasserman, who had

once been Hitch's agent, wanted to get the master back in form and ordered the story

department to present him with a list of more suitable properties from which the

director chose Uris' novel. What struck him about the story was its realistic depiction

of modern espionage as it told of a French agent working with the CIA to uncover

a double agent and information about Soviet missiles in Cuba in the tense days preceding

the Cuban missile crisis. This fit with Hitch's interest in producing a realistic

James Bond film while hopefully showing audiences that he could adjust to changing

times.

The trouble started with the screenplay. Initially, he hired Uris to adapt his

own novel, but the two never hit it off. Uris didn't care for Hitchcock's eccentric

sense of humor, nor did he appreciate the director's habit of monopolizing all of

his time as they worked through a script. He was also confused by contradictory

demands that he make the film a realistic, modern espionage drama but draw inspiration

from the director's glamorous 1946 spy film, Notorious. For

his part, Hitchcock was disappointed that Uris seemed to ignore his requests to

humanize the story's villains. In his opinion the novel painted them as cardboard

monsters. With only a partial draft completed, Uris left the film.

With location shooting in Copenhagen and Paris set to start in a few months, Hitchcock

had to scramble to find a new writer. The director's assistant, Peggy Robertson,

proposed John Michael Hayes, who had written Rear Window (1954)

and To Catch a Thief (1955), but Hitch nixed the idea. The studio

approached Arthur Laurents, who had scripted Rope (1948), but

he said no. Finally, Hitchcock rushed Samuel Taylor, who had worked on Vertigo (1958), onto the film. For one of the few times in his career, the director went into production without a finished script. Taylor was submitting scenes throughout

the shoot, often the same morning a scene was scheduled to be filmed.

Hitchcock also had trouble with casting. After a bad experience directing established

star Paul Newman in Torn Curtain, the director decided he wanted

to create a star of his own for the film, rejecting suggestions that he hire Sean

Connery or Yves Montand to play the French spy. Instead he hired Frederick Stafford,

a Swiss actor he had seen in a French spy film. He had hoped to turn Stafford into

the new Cary Grant, only to discover the actor was much more limited in his talents.

The key role of Stafford's Cuban mistress, a character modeled on Fidel Castro's

sister, was uncast until they returned to Hollywood to shoot on the Universal back

lot. Then Hitch discovered Karin Dor, a German actress who had been a Bond girl

in You Only Live Twice (1967). Although she wasn't one of his

trademark blondes, he lavished attention on her, hoping to turn her into a major

star. But when she resisted his requests to adopt a sexy pose during a photo shoot

and wouldn't do a topless scene because of surgical scars, he lost interest. The

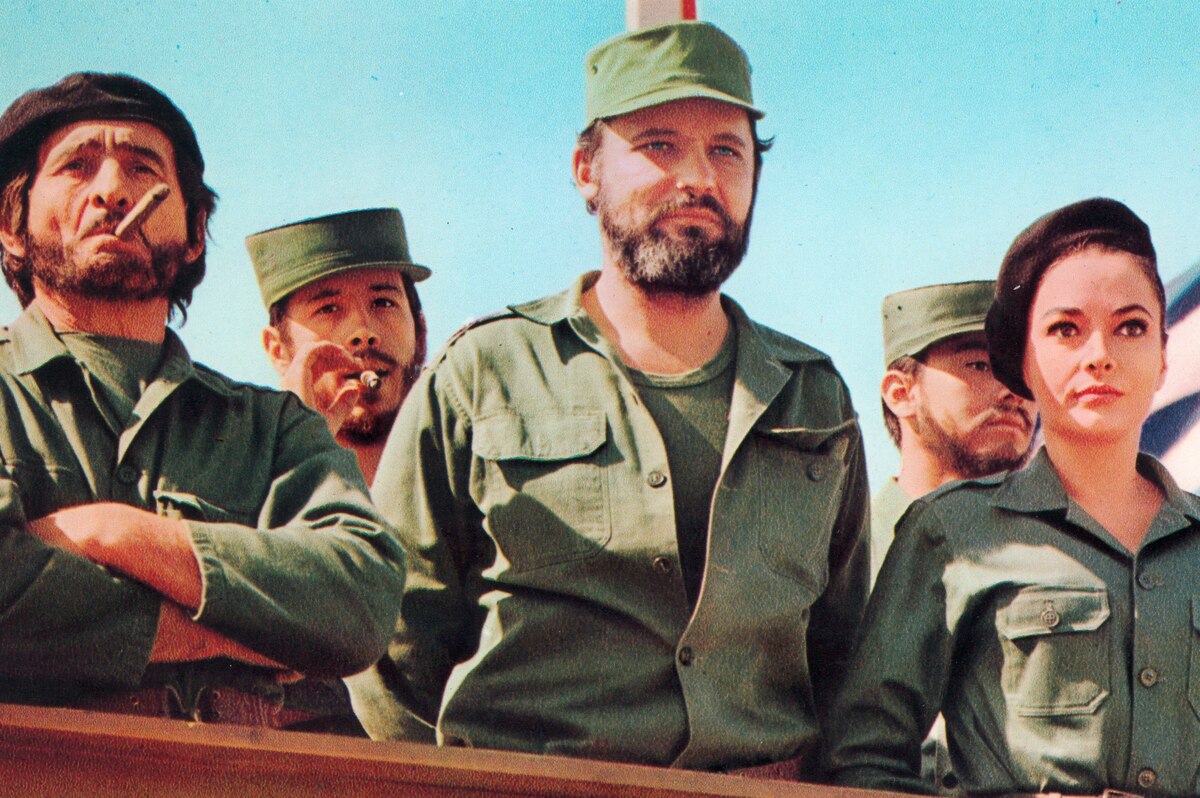

film contained two stand-out performances -- John Vernon, later Dean Wormer in Animal House (1978), as the Cuban leader and Roscoe Lee Browne as an operative infiltrating a Cuban enclave in Harlem -- but they were in supporting roles only

on screen for a small portion of the film's running time.

The one area where the film excelled was in its design. Working with Bumstead,

Hitchcock devised a carefully arranged visual scheme that worked key colors and

floral references throughout the mise en scene to parallel the story's development.

The strongest effect in the film was reserved for the death of Dor's character.

Shot from overhead, the scene showed her purple dress flaring out like a grotesque

flower as she falls dead onto a black tile floor. "Just before John Vernon

kills her," Hitchcock explained (in Alfred Hitchcock: The Dark Side

of Genius by Donald Spoto), "the camera slowly travels up and doesn't

stop until the moment she falls. I had attached to her gown five strands of thread

held by five men off-camera. At the moment she collapses, the men pulled the treads

and her robe splayed out like a flower that was opening up. That was for contrast.

Although it was a death scene, I wanted it to look beautiful."

As shooting drew to a close, more problems developed. As originally scripted, the

film was to end with a spectacular pistol duel between Stafford and the double agent

in a French soccer stadium. But part way through shooting, Hitchcock had to race

back to Los Angeles because his wife had suddenly taken ill. He left his associate

producer, Herbert Coleman, to finish shooting the scene. During test screenings,

audiences laughed at the old-fashioned duel. Bowing to studio pressure, Hitchcock

shot an ending he actually liked better -- a cynical airport scene in which Stafford

allows the mole to escape onto a Moscow-bound jet. This only confused preview audiences, though, so as a compromise he used existing footage to create a new ending in which the double agent commits suicide. Eventually, the studio decided to release different endings in different countries: the suicide in the U.S. and France, the airport

ending in England. The duel was thought lost until after Hitchcock's death, when

his daughter, Patricia, found it in her father's garage and donated it to the Academy

of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences®.

Topaz opened to scathing reviews in most areas, though the French,

long champions of Hitchcock's genius, gave it almost unanimous raves. Although

later critics would reevaluate the film in the context of Hitchcock's entire career

and his comeback with Frenzy three years later, audiences weren't

impressed. Although the film bore the largest budget of any Hitchcock film, $4

million, it only brought in $3 million at the box office.

Producer-Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Samuel Taylor, based on the Novel by Leon Uris

Cinematography: Jack Hildyard

Art Direction: Henry Bumstead

Music: Maurice Jarre

Cast: Frederick Stafford (Andre Devereaux), Dany Robin (Nicole Devereaux), Claude

Jade (Michele Picard), Karin Dor (Juanita de Cordoba), John Vernon (Rico Parra),

Michel Piccoli (Jacques Granville), Philippe Noiret (Henri Jarre), Roscoe Lee Browne

(Philippe Dubois), John Forsythe (Michael Nordstrom).

C-126m. Letterboxed. Closed captioning.

by Frank Miller

Topaz

by Frank Miller | August 25, 2004

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM