During the studio era, when scores of motion pictures were cranked out on a

weekly basis, many performers wound up being typecast in particular kinds of

roles. It was the nature of the assembly-line beast. Bigger talents, for

the most part, had no problem with this, since they were able to

occasionally move between their accepted personas and other types of

characters. But lesser actors were often forced to inhabit exactly the same

character over and over again, throughout their careers. Their public

practically demanded it.

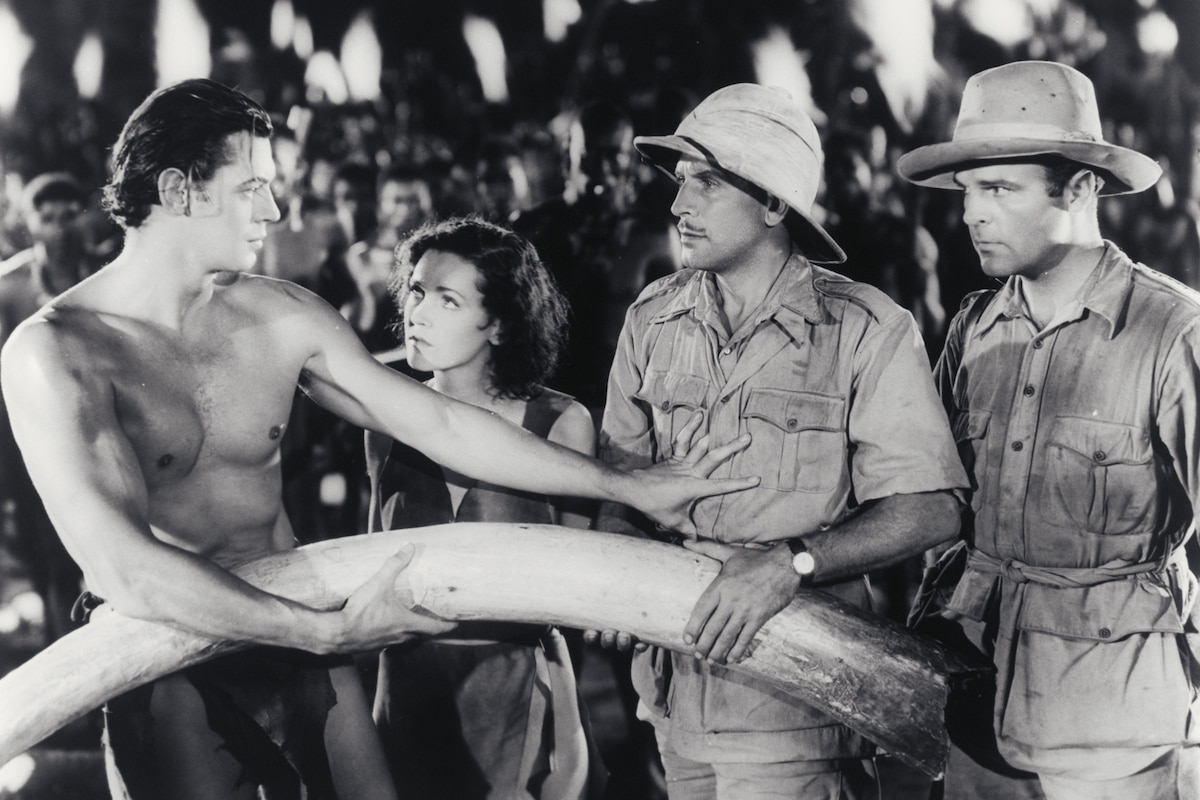

Johnny Weissmuller is the best example of this. All anybody knew about him

when he was cast as Tarzan, King of the Jungle, was that he was a champion

amateur swimmer, was strikingly handsome, and couldn't act a lick. And that

was all anybody knew about him 12 movies and 16 years later, when he finally

quit playing Tarzan and took on the less-heralded role of Jungle Jim.

Tarzan and His Mate (1934) was the second, and easily the most memorable, of

Weissmuller's Tarzan pictures. It's briskly paced, beautifully

photographed, and features a racy swimming sequence that was censored at the

time of the movie's release. All that, and you get to see Tarzan wrestle a

rubber alligator!

This time around, Harry Holt (Neil Hamilton), who visited the jungle in the

first movie, returns to Africa looking for ivory. He's accompanied by his

friend, Martin Arlington (Paul Cavanagh). Holt also intends to bring Jane

back to "civilization" with him, not that she's particularly interested in

returning. Tarzan, for his part, will eventually try to stop Holt's

expedition from plundering ivory from the sacred elephant burial grounds,

and will confront an assortment of wild animals in the process. It's not

exactly War and Peace, but it didn't need to be.

Back in 1934, the scene that caused all the commotion was available in three

different versions that were edited by MGM to meet the standards of

particular markets. However, the original one was restored when Ted Turner

issued Tarzan and His Mate on video in 1991. In it, Tarzan and Jane

(in this instance, O'Sullivan's swimming double, Josephine McKim) dance a

graceful underwater ballet...and Jane is completely nude! Then, when she

rises out of the water, O'Sullivan (now re-assuming the role) flashes a bare

breast. Such big-screen impropriety was virtually unheard of at the time,

and the Production Code Office had a fit. O'Sullivan's scant costume, when

coupled with her utterly inescapable sexual charisma, was bad enough.

Censors certainly didn't need her, or anyone else, stripping off on-screen before they

went swimming.

Who knows how or why MGM thought it could get away with such a move. The

sequence may well have made it as far as it did due to the confusion

surrounding the entire production. Less than a month into shooting, the

original director, Cedric Gibbons, was replaced by Jack Conway, although

there's no record of exactly why this happened. Then Rod La Rocque was

replaced by Paul Cavanagh. William Stack and Desmond Roberts also stepped

in, taking over roles that had originally been cast with other

actors.

When filming was finished, Gibbons promptly went back to his old job as an

MGM art director. He worked on literally hundreds of pictures between 1924

and the late 1950s, but, for whatever forgotten reason, Tarzan and His

Mate was the only one he ever directed. In later years, to confuse

things even further, O'Sullivan insisted that most of the film was actually

directed by James C. McKay! She also, according to her actress daughter,

Mia Farrow, used to refer to her ornery cast mate, Cheetah the

chimpanzee, as "that bastard."

Whatever the production's problems - whether human or monkey-related -

Weissmuller certainly wasn't among them. He knew he was a limited

performer, and was willing to throw himself into any sequence, even going so

far as to briefly ride a rhinoceros, a move that didn't exactly please his

wife, actress Lupe Velez. However, Alfred Codona doubled for Weissmuller

when Tarzan was required to swing through the trees, and a man named Bert

Nelson wrestled the lions. Weissmuller may have been enthusiastic, but he

certainly wasn't an idiot.

As time goes on, people may remember that Weissmuller was a multiple Olympic

gold medal winner, but they probably don't realize just how gifted he was.

Before Mark Spitz shattered several world records at the 1972 Olympics,

Weissmuller was considered the greatest swimmer who ever lived. You don't

get nicknames like "The Human Hydroplane," "The Prince of Waves," and "The

Aquatic Wonder" for nothing.

From the moment Weissmuller entered competitive swimming in 1921, until he

retired seven years later, he never lost a race. Never. During the 1920s,

he racked up 36 individual AAU championships and 67 world championships. He

was also the first swimmer to break the one-minute mark in the 100 meters,

and eventually held 51 world records and 94 American records. After a

career like that, playing Tarzan was almost a step down, although

Weissmuller was paid handsomely to do it.

Producer: Bernard H. Hyman

Director: Jack Conway, Cedric Gibbons

Screenplay: Leon Gordon, James K. McGuinness, Howard Emmett Rogers

Cinematography: Charles G. Clarke, Clyde De Vinna

Film Editing: Tom Held

Art Direction: A. Arnold Gillespie

Music: William Axt, Paul Marquardt, George Richelavie, Fritz Stahlberg

Cast: Johnny Weissmuller (Tarzan), Maureen O'Sullivan (Jane Parker), Paul Cavanagh (Martin Arlington), Forrester Harvey (Beamish), Nathan Curry (Saidi), William Stack (Pierce).

BW-91m.

by Paul Tatara

Tarzan and His Mate

by Paul Tatara | May 24, 2004

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM