SYNOPSIS

Convinced the Russians have invented water fluoridation as a means of sapping the "precious bodily fluids" of America's men, the mad General Jack D. Ripper launches a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union from his command post at Burpelson Air Force Base. As worldwide destruction looms, Stanley Kubrick's landmark black comedy cuts back and forth between the base, where British liaison officer Captain Mandrake tries in vain to learn Ripper's secret attack code and turn the bombers back; the War Room in Washington, D.C., where President Muffley works to head off disaster by convincing the Soviet premier it was all a mistake, and the cockpit of a B-52 commanded by Major "King" Kong, a gung-ho patriot determined to reach his target at all costs.

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Producer: Victor Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Terry Southern, Peter George (based on his novel, Red Alert)

Cinematography: Gilbert Taylor

Editor: Anthony Harvey

Production Design: Ken Adam

Art Direction: Peter Murton

Music: Laurie Johnson

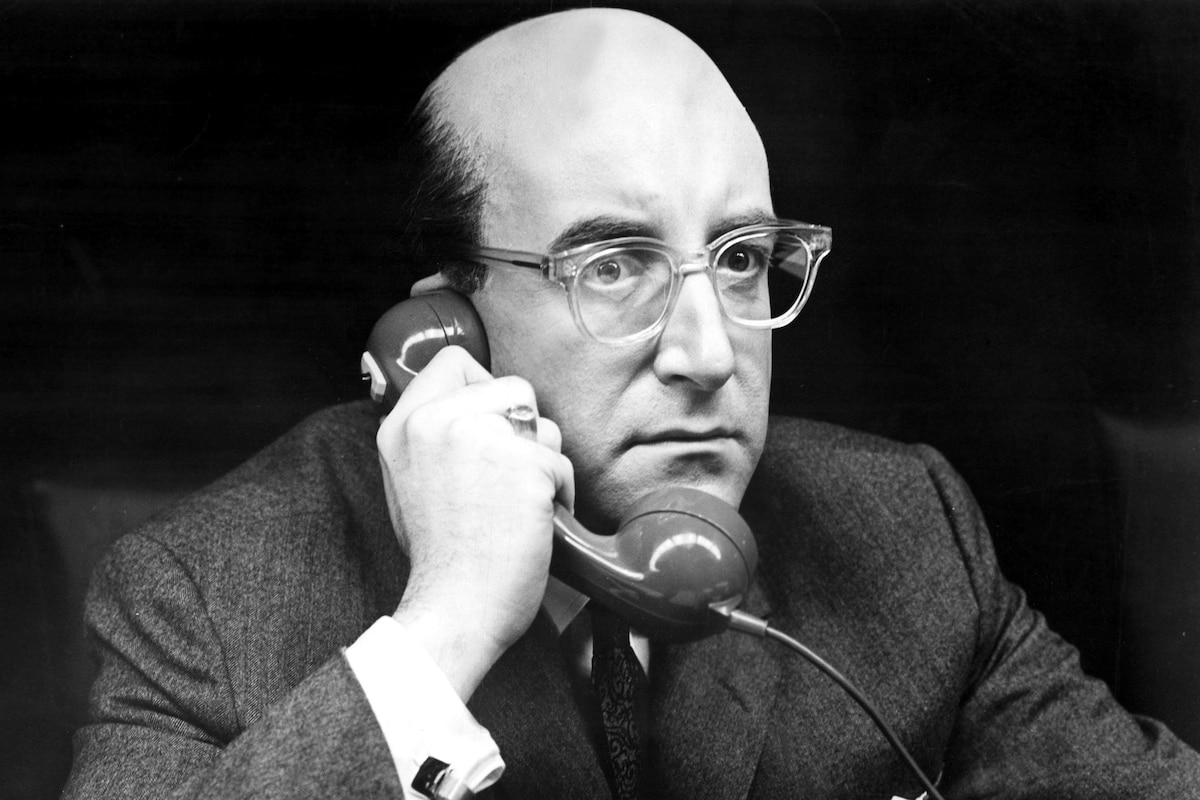

Cast: Peter Sellers (Capt. Lionel Mandrake/President Merkin Muffley/Dr. Strangelove), Sterling Hayden (Gen. Jack D. Ripper), Keenan Wynn (Col. "Bat" Guano), Slim Pickens (Major T. J. "King" Kong), James Earl Jones (Lt. Lothar Zogg).

BW-149m. Letterboxed. Close captioning.

Why Dr. Strangelove is Essential

On the surface, the plot of Dr. Strangelove sounds like a suspense film designed to hold viewers on the edge of their seats. But even a quick glance at the absurd character names alerts us to the fact that Kubrick and company are up to something else. That Dr. Strangelove manages to be frightening while also delivering one of the most savagely funny satires ever put on film is what makes this Cold War-era classic still so powerful and enjoyable today. Stanley Kubrick creates a pile-up of insane incongruities that propel the story toward its horrifying conclusion. Ripper is motivated not only by anti-Communist zealotry but by a sexual dysfunction for which he needs a scapegoat. Armed Services Commander General Buck Turgidson isn't merely an enthusiastic hawk but a rampant hedonist who equates war with sexual conquest. Colonel Bat Guano is a first-rate soldier on a mission to storm Ripper's office and head off disaster. Not only does he hold a strong contempt for commie "preverts," but also an overwhelming concern for corporate property, even as the world races toward destruction. And the German scientist and advisor to the president, Dr. Strangelove, is a wheelchair-bound fanatic with a mechanical hand that keeps threatening to break into a Nazi salute. Strangelove's mad plan to save humanity is to install society's male elite and a proportionately larger contingent of beautiful women in underground hideouts until the radioactivity is low level......almost 80 years later!

Much has been made of the sexual imagery and jokes in the film. The opening credits roll to the romantic strains of "Try a Little Tenderness" as a B-52 bomber emerges from the clouds to refuel with an airborne tanker in a mechanical evocation of human coupling. And one of the last human images places the H-bomb like a swollen phallus between Kong's legs. From beginning to end, Kubrick equates the warring impulse to male sexual drive, much of it bound up in the sexual obsessions of the two most militant characters, Ripper (who denies his "essence" to women and hoards his "precious bodily fluids") and Turgidson (first seen in a sexual romp with his secretary, who is also the Playboy centerfold ogled by the bomber crew). Even the names of the characters resonate with sexual in-jokes: Mandrake (a medicinal root believed to increase potency), Turgidson (from "turgid," meaning swollen), Merkin Muffley (combining two terms referring to the female pubic area) and, perhaps stretching it a bit, Strangelove. Anyone familiar with the work of the writer Terry Southern - The Loved One (1965), Barbarella (1968), and the novels Candy (1968) and The Magic Christian (1969), will recognize his hand in these elements of the screenplay.

But it would be a mistake to view Dr. Strangelove as just one long sex joke. What really captured audiences of its day was its depiction, however comic it may have been, of what many considered an entirely plausible scenario. When the film was released early in 1964, the Cold War was very much "in progress" and the Soviet Union was still regarded as a major threat to world peace and national security. The hawk like attitude of military officers like Turgidson and Ripper wasn't that far removed from the rhetoric surrounding our excursions into Laos and, soon after, Vietnam and the Dominican Republican. Most of all, it had only been 15 months since the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world closer to nuclear war than it had been before or since. The same year Kubrick's film came out, another picture on the same theme, Fail Safe, was released. That movie took a more melodramatic approach, depicting honorable people battling a system out of their control. Kubrick's absurdist humor, on the other hand, put human folly firmly at the root of global disaster and drove the point home by letting audiences in on the joke; some situations are so horrendous you simply have to laugh in disbelief.

To add to the irony and incongruity fueling the film's humor, Kubrick for the first time effectively juxtaposes music and image in ways he would explore even more deeply in later work. Of course, there's that sensual bomber scene at the beginning played out against a tender love song. Then, in the film's final moments, the director places stock footage of nuclear explosions over Vera Lynn's popular World War II ballad "We'll Meet Again" - a sweet and comforting voice singing "Will you please say hello to the folks that I know/Tell them I won't be long/They'll be happy to know that as you saw me go/I was singing this song" while the world is blown to bits. Kubrick carried this music-versus-image technique into his later films, notably in the lilting strains of "The Blue Danube" underscoring the coldly mechanical but somehow lyrical motions of spacecraft in orbit in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). And for any viewer of A Clockwork Orange (1971), neither "Singing in the Rain" nor Beethoven's Ninth Symphony will ever sound the same again.

By Rob Nixon

The Essentials - DR. STRANGELOVE (1963)

by Rob Nixon | March 30, 2004

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM