One of the most fascinating titles to receive a recent DVD debut from Fox Cinema Archives is The Moon is Down (1943), a powerful war drama with a philosophical slant. It was the fourth movie to be adapted from the published work of John Steinbeck, following Of Mice and Men (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and Tortilla Flat (1942). Published in 1942, The Moon is Down was immediately adapted by Steinbeck himself into a play, which ran for two months on Broadway in the spring of 1942 starring Otto Kruger and Ralph Morgan. Twentieth Century-Fox quickly snapped up the screen rights for $300,000, the most ever paid for a novel up to the time.

Steinbeck's story of an evil military force occupying a nameless country had been written as an allegory, as something to foster philosophical thinking about the nature, consequences and morality of war and power, but for the movie, screenwriter/producer Nunnally Johnson made the names specific: the evil force was Nazis and the nameless country was Norway. It had been obvious to readers and theatergoers that a Nazi occupation of a Scandinavian country is what Steinbeck had in mind anyway; making it explicit, the film would carry more visceral relevance and propaganda value to moviegoers at the height of WWII.

Far more controversial was the characterization of the villain of the piece, the Nazi commander Col. Lanser, as intelligent, thoughtful, and altogether human. This was a far cry from the norm, and even today it is startling to see a Nazi in a 1943 film being portrayed as anything other than all-out evil. Make no mistake: Lanser is cruel and bad, just not simplistically so. He is also cultured and ruminative, and while he cares nothing about killing people, he only wants to do so if it will serve a useful purpose -- and he does not think mere killing will quell the urge of the Norwegian villagers to resist. Some critics of the era contended that Lanser was too human, but in fact his intellect makes his brutality all the more appalling and dangerous.

Cedric Hardwicke is outstanding as the blasé Lanser, which was a very hotly contested role in Hollywood at the time. Nunnally Johnson later said that he held talks with Orson Welles about playing the part, and tested other actors including Charles Laughton, Conrad Veidt and George Sanders.

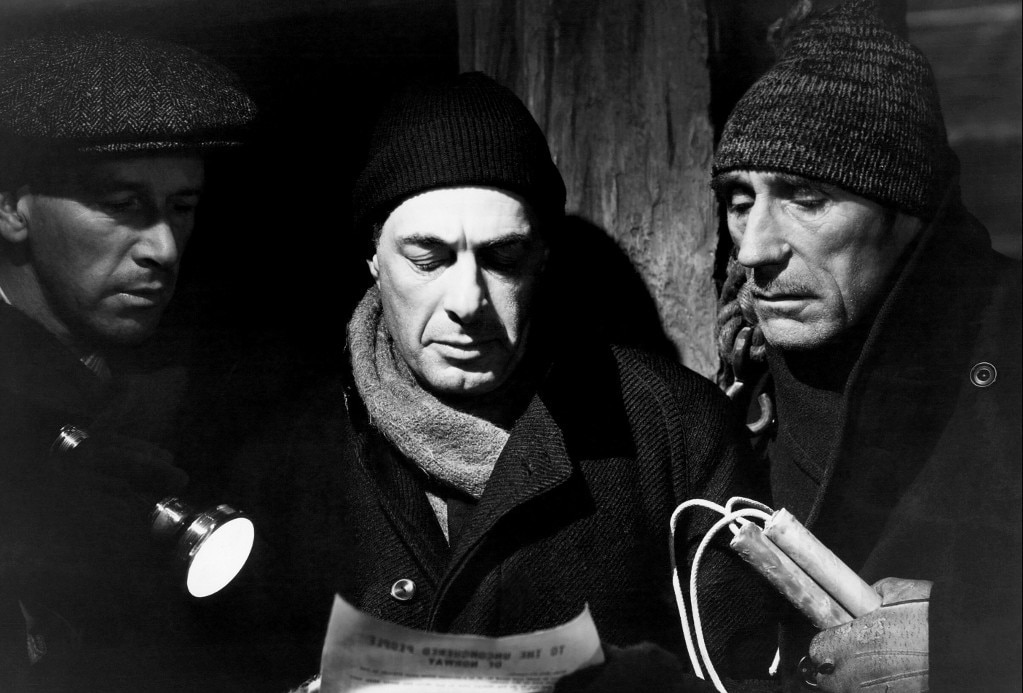

The surface narrative of The Moon is Down is basically comprised of the Nazis easily invading a Norwegian town, forcing the villagers to operate their iron mine for the Nazis' gain, and the villagers resisting more and more, eventually with the help of airdropped weapons. But a large part of the film is an examination of the status quo in the form of a battle of minds and words between Col. Lanser and the two village leaders -- the mayor (Henry Travers) and the doctor (Lee J. Cobb). Lanser can't understand why the villagers wouldn't stop resisting if their leaders were killed, and the mayor and doctor can't understand why the Germans would think they wouldn't keep resisting. The politeness and earnestness of the dialogue exchanges makes for a powerful contrast with the very subject being debated. At times these dialogue-heavy scenes approach getting too contrived or theatrical, but the power of the words and their expert delivery ultimately wins out.

The Moon is Down grabs you right away with its striking title sequence of a map of Norway lying on a table, with what is meant to be Hitler's voice shrieking on the soundtrack in German and pointing at the map. And the film has a great ending, which, while predictable, is powerful and unexpected in the way that it unfolds. Through the bulk of the picture, director Irving Pichel and his cameraman Arthur Miller achieve starkly beautiful black-and-white visuals, including some memorable moments like the removal of hats before a hanging. The film used the same sets from How Green Was My Valley (1941), and certain camera angles are instantly recognizable.

Nunnally Johnson had produced and written The Grapes of Wrath, for which he was Oscar-nominated, and he did the same on this picture, working closely with Steinbeck. A former newspaper reporter, Johnson was one of the most prolific writers of "quality" films in Hollywood. He was also a good producer, surrounding Hardwicke, Travers and Cobb with an outstanding supporting cast right down to the bit players.

Peter Van Eyck in his screen debut plays a lonely Nazi desperate for some friendly social interaction with the bewildered locals; ultimately he meets his match in a village woman played well by Dorris Bowden. Bowden was an attractive actress on her way up in Hollywood, but she retired from the screen after this film when she gave birth to her first child -- with husband Nunnally Johnson!

E.J. Ballantine is perfect as the traitorous villager really in cahoots with the Nazis, a role he originated on stage. (He was the only holdover from the stage production.) Director Irving Pichel himself plays the innkeeper, a character that Johnson had written with Pichel in mind -- before Pichel was then chosen (by Johnson) to direct.

In smaller bits, look among the villagers for Jeff Corey, Charles McGraw, and five-year-old Natalie Wood in her second film (though the first to be released) as a little girl who is too scared to tell a German soldier her name. Pichel had discovered Wood, whose real name was Natasha Gurdin, in Santa Rosa, Calif., while casting Happy Land (1943), and he used her in that film, in The Moon is Down, and then in Tomorrow is Forever (1946), her first significant role.

John Steinbeck regularly visited the set. Later he wrote Johnson a letter with his impressions: "It seems to me you are getting on film some rather unique thing that I have only seen in one or two films in my life. There is a curious third dimension. I don't know how this is done, whether by lighting or photography or by the placing of the people, but it did seem that one looked deep into a scene rather than simply at it."

The Moon is Down looks and sounds perfectly acceptable on Fox Cinema Archives' no-frills DVD-R. The company has also just released two interesting curiosities from the same era: Berlin Correspondent (1942), starring Dana Andrews, and The Loves of Edgar Allan Poe (1942), starring Linda Darnell and Shepperd Strudwick (credited as "John Shepperd"). Both were produced by Bryan Foy when he was briefly working at Fox, and both look OK on DVD-R seventy years later.

By Jeremy Arnold

The Moon is Down on DVD

by Jeremy Arnold | June 05, 2013

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM