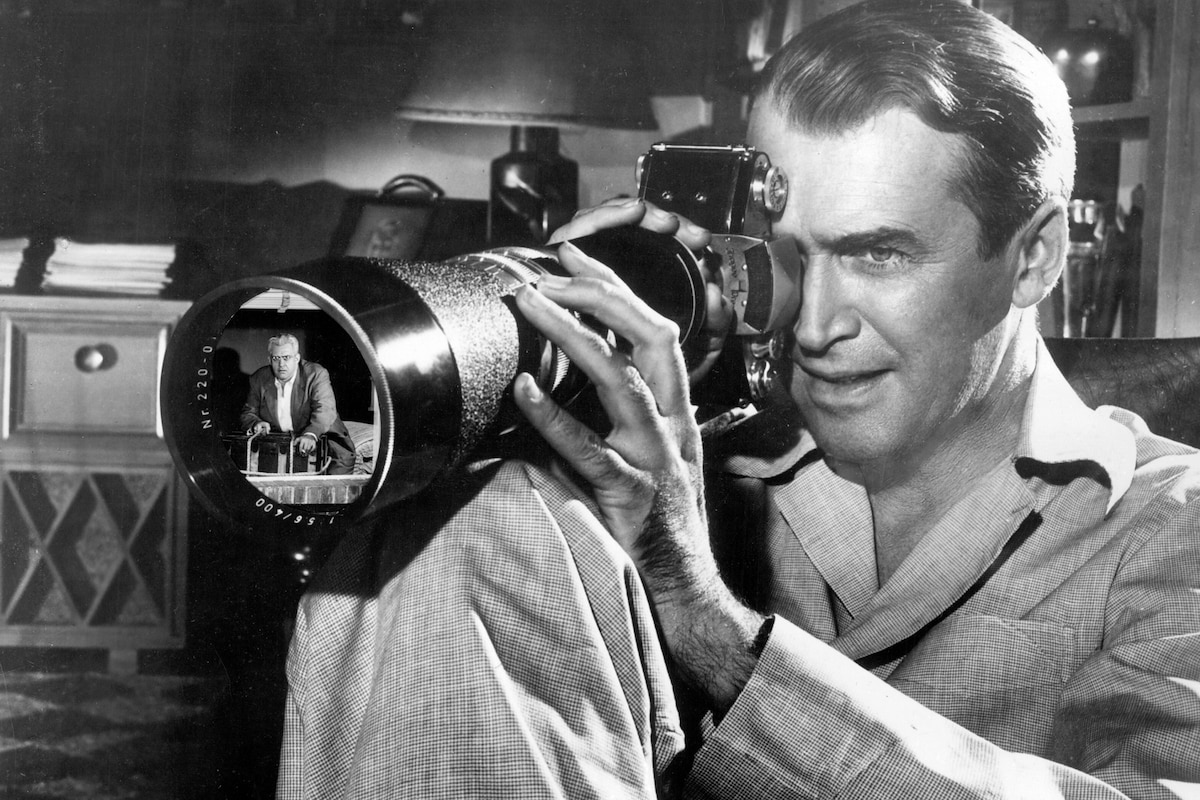

In Rear Window, one of director Alfred Hitchcock's greatest achievements, James Stewart plays a worldly news photographer confined to a wheelchair in his apartment, having suffered a broken leg. It's a sweltering summer in Greenwich Village, and to pass the time, Stewart takes to spying on his neighbors across the courtyard. In the course of his spying, he begins to suspect his neighbor (Raymond Burr) of murdering his wife. Naturally police detective Wendell Corey doesn't believe him, so Stewart and his breathtakingly gorgeous girlfriend, Grace Kelly, try to prove it on their own. Along the way, Stewart watches the other inhabitants of the building play out their own little stories. Like little movies themselves, they are full of humor, drama, and tragedy.

Hitchcock later said of making this picture, "I was feeling very creative at the time. The batteries were well charged." Any scene of the movie proves this point. Take the opening: within seconds after the credits, we know who James Stewart is, what he does for a living, and why is confined to a cast and a wheelchair, all without a word of dialogue. It's extremely economical visual storytelling, and the great beauty of Rear Window is that you can notice such techniques while still simply being entertained. The film is so overflowing with suspense, romance, and comedy that it looks like it was the easiest, most effortless movie in the world to make. Hitchcock knew that audiences love to work - to piece things together visually, to understand relationships through editing, staging or camera movement, and that is why Rear Window is so captivating.

The strong subjective point of view of "us-watching-Stewart-watch-neighbors" was actually embodied in the original Cornell Woolrich story, It Had to be Murder (1942), on which the screenplay was based. But Woolrich's yarn contained only the murder storyline. There was no Grace Kelly, no Thelma Ritter (Stewart's housekeeper), no policeman or other neighbors. Hitchcock wanted to expand it and laid out his ideas to writer John Michael Hayes. He also asked Hayes to spend some time with Grace Kelly, at the time working on Hitchcock's Dial M For Murder, because he wanted her for the new picture. Hayes and Hitchcock both found Kelly's acting in Dial M to be stiff - despite the fact that neither man saw any inhibitions in her in real life. So Hayes wrote the part for her, consciously trying to work in her natural charm and outgoing nature.

A 35-page treatment was good enough for Hitchcock, Stewart and Paramount all to commit to the project, and Hitchcock then left Hayes alone to write the script. The director liked what he read, and then, remembered Hayes, turned 200 numbered scenes into 600 by inserting all his previsualized camera setups.

Shooting was done entirely in a soundstage on the Paramount lot. (With few dramatic exceptions, the camera never leaves Stewart's apartment during the movie.) Studio art director Henry Bumstead, at the cusp of a distinguished and still ongoing career (credits include Vertigo, To Kill a Mockingbird, Unforgiven, and Mystic River), had the idea of cutting out the floor of the stage so that the basement could function as the courtyard level, with Stewart's apartment on the main stage floor. The set "went all the way from the basement to the grids." Sound was recorded live from Stewart's window across the stage, in order to achieve a hollow, distanced effect which reinforced the audience's alignment with Stewart.

Universal's new "Collector's Edition" DVD contains a fine transfer of a beautifully restored print as well as some worthwhile extras. Aside from a trailer, production stills, and DVD-ROM features, viewers will find an interview with John Michael Hayes and a 1-hour documentary entitled "Rear Window Ethics: Remembering and Restoring a Hitchcock Classic," which contains interviews with a host of cast and crew members. Both featurettes are extremely informative and well-produced, and Hitchcock himself can be heard in a few audio clips of an interview he gave Peter Bogdonavich many years ago. In one clip, he shares the secret of how to shoot a fight scene, explaining that the climactic fight of Rear Window is all close-ups of hands, feet, heads, etc. As an experiment, he also shot it in longshot and says there was no comparison.

Also in the documentary, film restorers Robert Harris and James Katz discuss the challenges of restoring Rear Window, explaining that the film's negative was in terrible shape. The yellow color layer had been stripped away due to repeated lacquering, and they spent six months developing a new restoration technique to put the layer back, something that had not been done before.

by Jeremy Arnold

Rear Window

by Jeremy Arnold | October 13, 2003

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM