According to biographer Joseph McBride, the origins of Close Encounters of the Third Kind most likely go back to Spielberg watching a spectacular meteor shower as a young boy in Phoenix and observing the desert skies through his telescope. He also voraciously read and watched science fiction books, movies, and TV shows.

As a child, Spielberg enjoyed and admired films that came out of the popular wave of science fiction of the 1950s and early 1960s, particularly those directed by Jack Arnold: It Came from Outer Space (1953), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957).

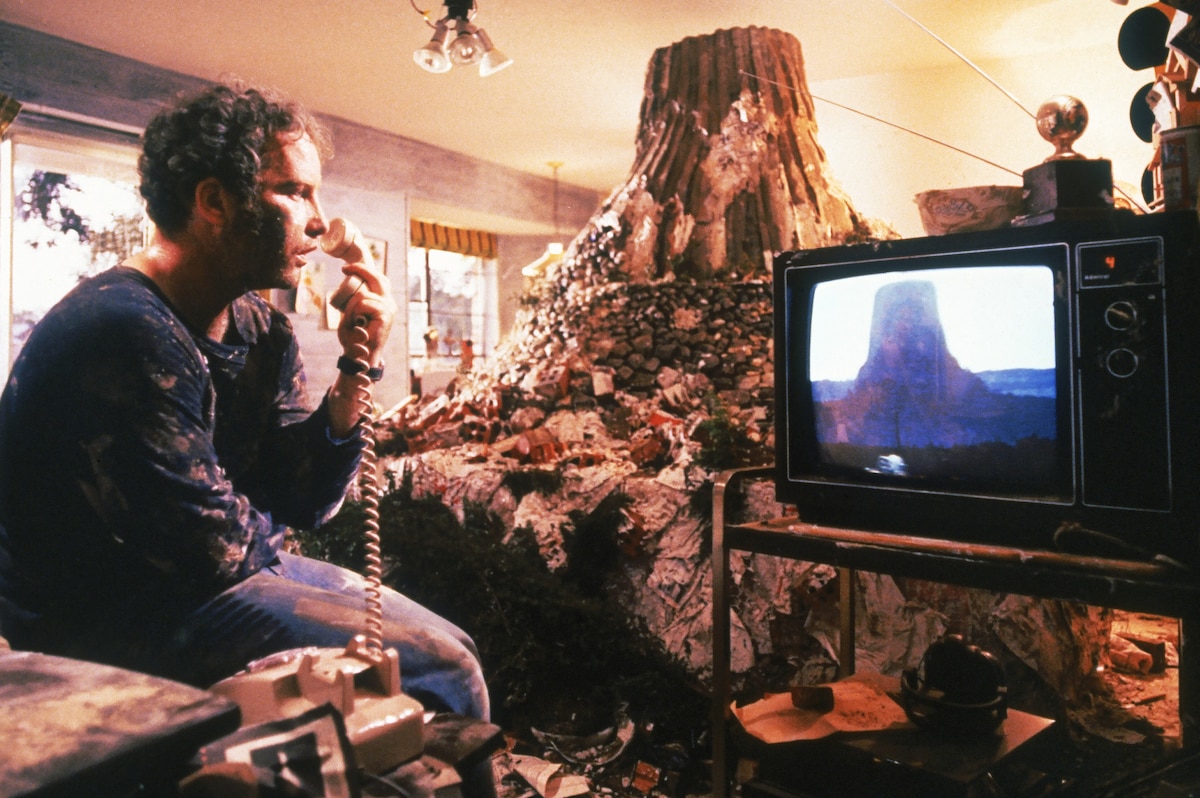

Spielberg has also credited two other childhood cinematic memories with being important to this movie's genesis. The first was the image of the mountain from the "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence in Disney's Fantasia (1940). The other was the song "When You Wish Upon a Star" from Pinocchio (1940). "I pretty much hung my story on the mood the song created, the way it affected me emotionally," he said. "The mountain became the symbolic end zone of the movie, and everything danced around that."

While living in Phoenix in 1964, at the age of 17, Spielberg made an 8mm sci-fi adventure film called Firelight on a budget of $500, shooting on evenings and weekends with a cast of high school drama students, that included his sister Nancy. The story centered on a group of scientists investigating sightings of colored lights in the sky and the subsequent disappearance of people, animals, and objects from the fictional town of Freeport, Arizona. Among the disappeared are a unit of soldiers and a little girl whose mother has a heart attack as a result. The story also featured marital discord between one of the scientists and his wife, and another scientist's obsessive efforts to convince the government that extraterrestrial life exists. Spielberg showed the movie at a local cinema and charged $1 per ticket; he made a profit of $1.

Years later, when seeking work in Hollywood, Spielberg gave two reels of Firelight to a producer to demonstrate his abilities. The production company soon folded and the two reels were lost.

Another basis for Close Encounters was a short story Spielberg wrote in 1970 called "Experiences," which was set in a small-town lovers' lane in the Midwest where young people witness a mysterious light show in the night sky.

Spielberg never let go of the idea of making a feature-length film about contact with aliens on Earth. He first considered making a documentary about people who believe in UFOs, or even a low-budget feature using ideas from his earlier film. He realized, however that to fulfill his vision would require state-of-the-art technology costing far more than he initially estimated. Nevertheless, he held on to the idea: "Somehow I would have found the money. It's a movie I'd wanted to make for over ten years."

By the early 70s, Spielberg was starting to make a name for himself as a skillful young director after a few television series episodes and a critically acclaimed TV suspense movie Duel (1971). He had been given a shot at a theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express (1974), starring Goldie Hawn. While in post-production on that movie, he became friendly with the producers Michael and Julia Phillips, who were producing The Sting (1973). Spielberg asked the couple if he could pitch his story to them, telling them only that it was about UFOs and Watergate. Now calling it "Watch the Skies," after the famous line from the end of the sci-fi classic The Thing from Another World (1951), the story focused on a government cover-up of UFOs and the secret Project Blue Book.

Although he had been working successfully at Universal, Spielberg felt he didn't want to be too tied to one studio, so he and the Phillipses took his idea first to Fox, whose commitment seemed too lukewarm to them. Then they went to David Begelman, the new head of Columbia, who was much more enthusiastic about the idea and about Spielberg. Not that there weren't reservations. At the time, sci-fi had not been a popular film genre since the 1950s. The success of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) notwithstanding, it was considered strictly B-movie material. But the financially ailing Columbia desperately needed a hit.

The group of people who frequently gathered at the Phillips' house in the summer of 1973 included future film writer and director Paul Schrader, who was then in development on the script for Taxi Driver (1976). Spielberg briefly flirted with the idea of directing that script and eventually agreed to be back-up director for it, a guarantee Columbia Pictures insisted on in the event that relative newcomer Martin Scorsese failed to meet their expectations. Schrader was raised in a very strict Dutch Calvinist family (so strict, he and his brother, screenwriter Leonard Schrader, were not allowed to see movies) and wrote the book Transcendental Style in Film (University of California, 1972), a study of the expression of the spiritual state in the works of directors Yasajiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, and Carl Dreyer. Columbia and Spielberg thought this background ideal for tackling a work that had spiritual undertones in its look at humanity's longing for contact with beings from beyond Earth. Schrader was contracted to write the script for "Watch the Skies" for $35,000 and 2.5 percent of the profits.

"Watch the Skies" was scheduled to shoot in the fall of 1974, but the script was proving more difficult to pull together than expected. Because of the delays, Spielberg took on another project for the money. This "movie about a shark" he was contracted for turned out to be his blockbuster breakthrough and one of the most successful movies of all time, Jaws (1975).

At a certain point in development, the premise shifted away from the government conspiracy. Spielberg told a European interviewer in 1978, "I didn't want to beat it to death because in the U.S. it's passé. We have lived through Watergate, the CIA, and people already find them redundant." Schrader said this shift away from the UFO cover-up story was his principal contribution. "I thought it ought to be about a spiritual encounter. That idea stayed and germinated." According to Michael Phillips, it was he who suggested to Spielberg that the aliens should be friendly.

Years later, Spielberg said he thought Schrader's script, titled "Kingdom Come," was "one of the most embarrassing screenplays ever professionally turned in to a major studio or director. ... Paul went so far away on his own tangent, a terribly guilt-ridden story not about UFOs at all." The protagonist whose life is transformed by an encounter on a deserted country road in Schrader's draft was an Air Force officer whose story closely resembled that of real-life UFO expert Dr. J. Allen Hynek. Both Spielberg and Schrader claimed credit for that character, a vestige of whom remains in the movie as Major Benchley, a character named after Peter Benchley, the author of Jaws.

Astronomer Hynek was a consultant to the U.S. Air Force on the Project Blue Book on Unidentified Flying Objects. He had been hired, he said, "to weed out obvious cases of astronomical phenomena--meteors, planets, twinkling stars, and other natural occurrences that could give rise to the flying saucers then being received." Once a confirmed skeptic, he eventually broke with the government and its mission to debunk UFOs at all cost and started his own Center for UFO Studies, if not as a true believer then at least as someone who had an open scientific mind to the possibility of visitors from outer space. In his 1972 book on the subject, he coined the term "close encounter." An encounter of the first kind was one in which a UFO is seen at close range but without any contact. The second type of encounter is one in which "physical effects on both animate and inanimate material are noted." A close encounter of the third kind is one in which the occupants of the unidentified craft are present.

As Schrader later put it, he and Spielberg had a falling out "over ideological lines." Schrader's protagonist, who is converted to a belief in UFOs after a close encounter, spends 15 years trying to pursue direct contact with aliens before eventually discovering the key to his mission lay not out in the universe but within himself. Spielberg had decided to make his lead character an ordinary civilian, an unremarkable man whose life has to change to meet the new challenge before him after his first encounter. Schrader refused to send off to another world "as the first example of Earth's intelligence, a man who wants to go set up a McDonald's franchise....Steven's infatuation with the common man was diametrically opposed to my religious infatuation with the redeeming hero--I wanted a biblical character to carry the message to the outer spheres."

Spielberg worked on a draft while he was editing and promoting Jaws. He thought his script was fairly well structured but that the characters were lacking. "Essentially I'm not a writer and I don't enjoy writing. I'd much rather collaborate. I need fresh ideas coming to me."

Spielberg was helped by Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins, who wrote the screenplay for The Sugarland Express. Others who were involved in the project were John Hill, who wrote the second draft after Schrader's departure, Jerry Belson, and, by some accounts, David Giler. According to Julia Phillips, whose account of the making of the picture is far from flattering or sympathetic to Spielberg, Columbia financed "one under-the-table rewrite after another."

Spielberg wanted the final credits to read "Written and Directed by Steven Spielberg." Julia Phillips, who had a bitter falling out with him during production, said that Spielberg made her pressure everyone who worked on the script to drop their rights to credit. Schrader said he did so at Spielberg's request, "something I've come to regret in later years, because I had points tied to credit. So I gave up maybe a couple of million dollars that way." Schrader said he was assured nothing of his original script was in the final draft, but when he read it he saw that a character he had created was still present in the part of the French scientist Lacombe. He also thought the story had a spiritual dimension that was originally introduced in his script, and even the notion of the five musical tones had its roots in one of his earlier ideas about five colors associated with the aliens.

Michael Phillips believes Schrader's exclusion from the credits is justified because he wrote "a very different film...a much more serious quest.... It just wasn't a Steven Spielberg film; it wasn't a joyous roller-coaster. Close Encounters is really Steven's script. It was a project that he had started in his childhood and had always wanted to do. He got help from his friends and colleagues here and there, but 99.9 percent is Steven Spielberg."

The filmmakers still had to deal with one other person who felt he had made unacknowledged contributions. Hynek wrote a sharp letter to the producers pointing out they were appropriating his terminology and ideas without credit or payment. As a result, they recruited him as technical consultant, and he was given a cameo as part of the crowd that welcomes the aliens at the end.

by Rob Nixon

Key source material for this section: Steven Spielberg: A Biography by Joseph McBride (Simon & Schuster, 1997)

The Big Idea - Close Encounters of the Third Kind

by Rob Nixon | December 30, 2011

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM