It's been a unspoken tenet of world cinema auteur worship that the film directors who persist with a single style or

voice or theme are preferable - admirable, obsessively cool, pure-hearted and cult-worthy - than filmmakers who wildly

vary their approach and/or subjects. Louis Malle, for example, never enjoyed the unalloyed ardor of cinephiles the way

fellow French New Wavers Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer did. While they relentlessly, and often

abstrusely, followed their singular visions, Malle tried virtually everything under the son - scandalous rom-com,

gritty '60s art film, anthropological documentary, Chekhov stagecraft, experimental American indie, quirky Tati-like

Parisian farce, autobiographical WWII dramas, you name it. From the beginning, Malle was up for anything, exuding more

of the air of a moviehead bon vivant than a serious artiste, and equally famous for his array of marriages and

liaisons. This kind of approach to moviemaking is not uncommon, and allows in any lengthy career elbow-room for a few

masterpieces - as are, for Malle, Au Revoir Les Enfants (1987) and, arguably, 1974's Lacombe, Lucien.

Black Moon (1975) has never been on that list, even for Malle fans who stump for the controversial achievements

of Murmur of the Heart (1971) and My Dinner with Andre (1981). A long-unseen product of the lingering

Art Film epoch, now brought to DVD by Criterion, Black Moon is a freak in the Malle filmography - the man's

only pan-European, proto-Surrealist-Freudian dream-film, with dollops of tangy dystopian sci-fi satire and Bergmanic

identity crisis dropped in like sour cream. As a film of its day, however, it's lovably archetypal, sharing crazy

style impulses and narrative impishness with the contemporaneous films of Luis Bunuel, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Harry

Kumel, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Roman Polanski, not to mention Jaromil Jires's Valerie and Her Week of Wonders

(1970) and Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend (1967). Perhaps this is a large reason why in 1975 the film was so

abjectly dismissed; Pauline Kael (always the go-to blabbermouthed voice of doom in those days, and the one most easily

consulted today) condemned it as "witless" and "deadly." Her biggest point is sound - Malle tries with Black

Moon to make a hallucinatory genius's film, a vision ostensibly bursting spontaneously from a unique, and even

drug-addled, consciousness. But Malle is a sensible man, with earthly, easily grasped priorities, and the two tastes

simply do not go well together.

Nearly half a century later, however, we're free of a weekly reviewer's narrow, short-term, zeitgeist-framed

perspective, and in today's light Black Moon is a bizarre artifact of a freer, seemingly utopian cinematic age,

when filmmakers trusted viewers to appreciate an experiment's zest and desire, and not worry too much about its

results. Set in a fantasy-future Europe where the landscape has been ravaged by armed combat between the sexes,

Malle's movie seems at first to be squaring off as a feminist (Malle was always interested in sexual exploitation as a

social problem, but he also often seemed just as interested in undressing his actresses). The rebel guerrilla forces

we see are all gorgeous women, captured and executed by an army of men, but this dynamic falls by the wayside, to some

degree, as we follow escapee Lily (Cathryn Harrison) through the rural chaos, and to a seedy estate overheated with

its own familial madnesses. The world of the film is, significantly or not, overrun with wildlife, from the first

road-busy badger (quickly smushed) to legions of millipedes, sheep, roaches, turkeys, and even a Shetland unicorn that

eventually speaks. A tribe of naked children are relentlessly chasing down a huge sow through the undergrowth. And so

on.

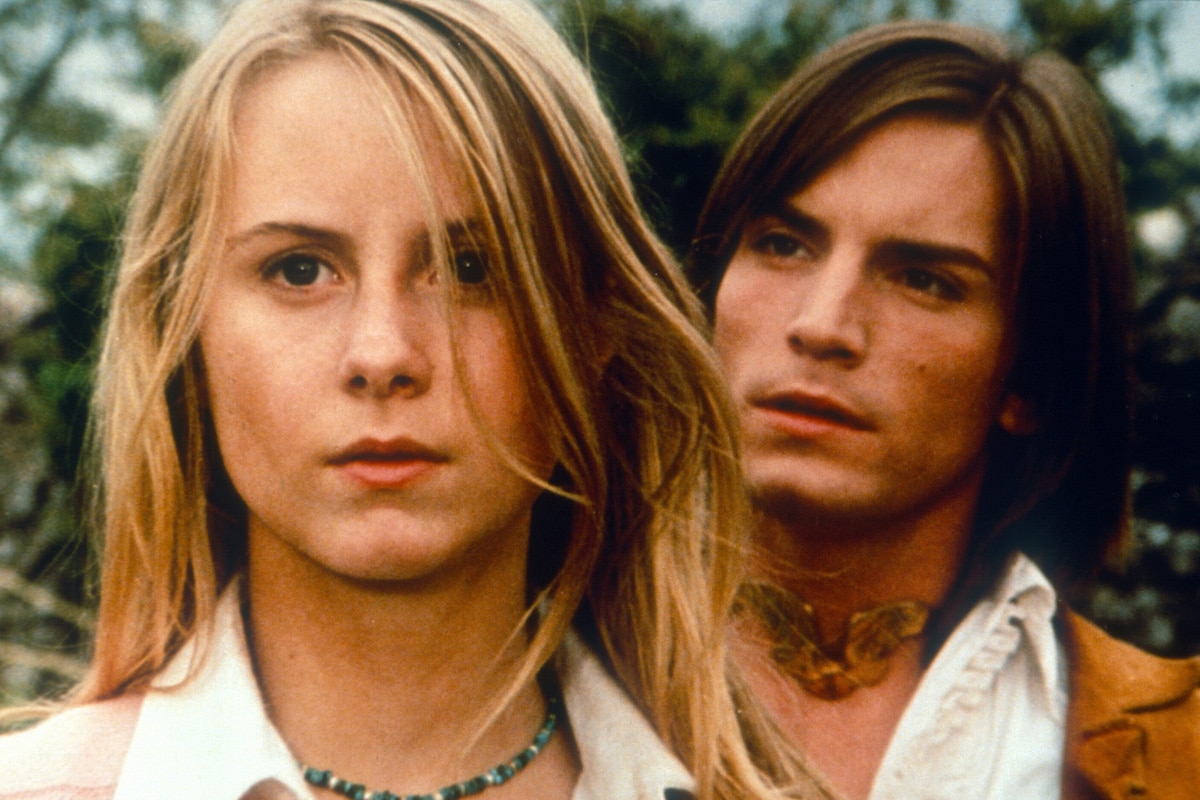

Irrationality is the watchword. In the house a brother-sister pair of exchangeable, androgynous identical twins (Malle

squeeze Alexandra Stewart and Warhol bad-boy Joe Dallesandro), who catatonically live out an ambiguous meta-sexual,

semi-parental relationship with each other and with "the old lady" (Therese Giehse), a bedridden octogenarian who, at

one point, is breast-fed by Stewart's ghostly dominatrix. A can-do Alice not so much lost in this particular,

symbol-ridden Wonderland as willfully exploring it for curiosity's sake, Lily takes it all in stride, looking for

answers but engaging in the absurdities as a child engages in a let's-pretend play scenario. As should we - the film

is rich in metaphoric possibilities, but its position toward the abstractly suggested sexual awakening of its heroine

is exultant and frivolous, not analytical, and in this sense Black Moon seems to comprise a sister-film of

Jires's Valerie, together a misty diptych of pubertal dizziness and zonked hormonal dreams.

Nobody makes films like this anymore, this whimsically risky. Malle certainly never did again, wherever his

peregrinations took him. All of 15, Harrison, Rex's granddaughter, doesn't act very much and isn't given much of a

chance, but she's pure moviestuff - blonde, willowy and placid in the way that makes responsible men grow half-lidded

and slackjawed. (Endearingly, her pimples come and go, scene to scene.) She's just one of the film's sensual affects;

Malle is interested only in textures and disjunctures, images and vibes, and the film is rather beautiful in its silly

inventiveness. Photographed by the legendary Sven Nykvist, shot entirely on Malle's estate in southern France, and

released in dubbed English, Black Moon comes to video with only a few Criterion-grade supplements, including an

alternate French soundtrack, an oddly dry essay by Ginette Vincendeau, and an old TV interview with Malle, in which he

enjoys trying to attach lofty meaning to the film's nonsequiturs.

For more information about Black Moon, visit The Criterion Collection. To order Black Moon, go to

TCM

Shopping.

by Michael Atkinson

Black Moon - Unlike Any Louis Malle Film You've Ever Seen Before!

by Michael Atkinson | April 23, 2011

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM