Kramer decided to premiere Judgment at Nuremberg in Berlin in December 1961 and asked his cast to be present. Most of them attended, except for Lancaster, who said he had other pressing matters (he was widely criticized for that although he gladly promoted the film later), and Dietrich, who was still concerned about the reaction of her countrymen, many of whom still hated her deeply for her efforts on behalf of the Allies during World War II.

Kramer made the premiere of Judgment at Nuremberg into a world event, flying in more than 300 reporters from 26 countries (120 columnists, critics, and political writers from New York alone). It was one of the most expensive press junkets of all time, running $150,000. The premiere took place December 14, 1961, and reporters noted that this was shortly after the Soviets had erected the Berlin Wall and one day before Adolf Eichmann was to be sentenced in Israel for war crimes.

There was a stunned silence at the close of the Judgment at Nuremberg screening in West Berlin, followed by applause, but only from the non-German press. German critics and reporters loudly condemned Kramer for stirring up the ghosts of the past and fueling hatred against their country. He responded that truth and justice must be shown and challenged German filmmakers to make movies about the Third Reich.

"The film was totally rejected: it never did three cents' business in Germany. It played so many empty houses, it just stopped. People asked how could I, an American, try to rekindle German guilt? Well, I said that it would indeed have been better if the Germans had made it, but the fact is they didn't. So I did." Stanley Kramer

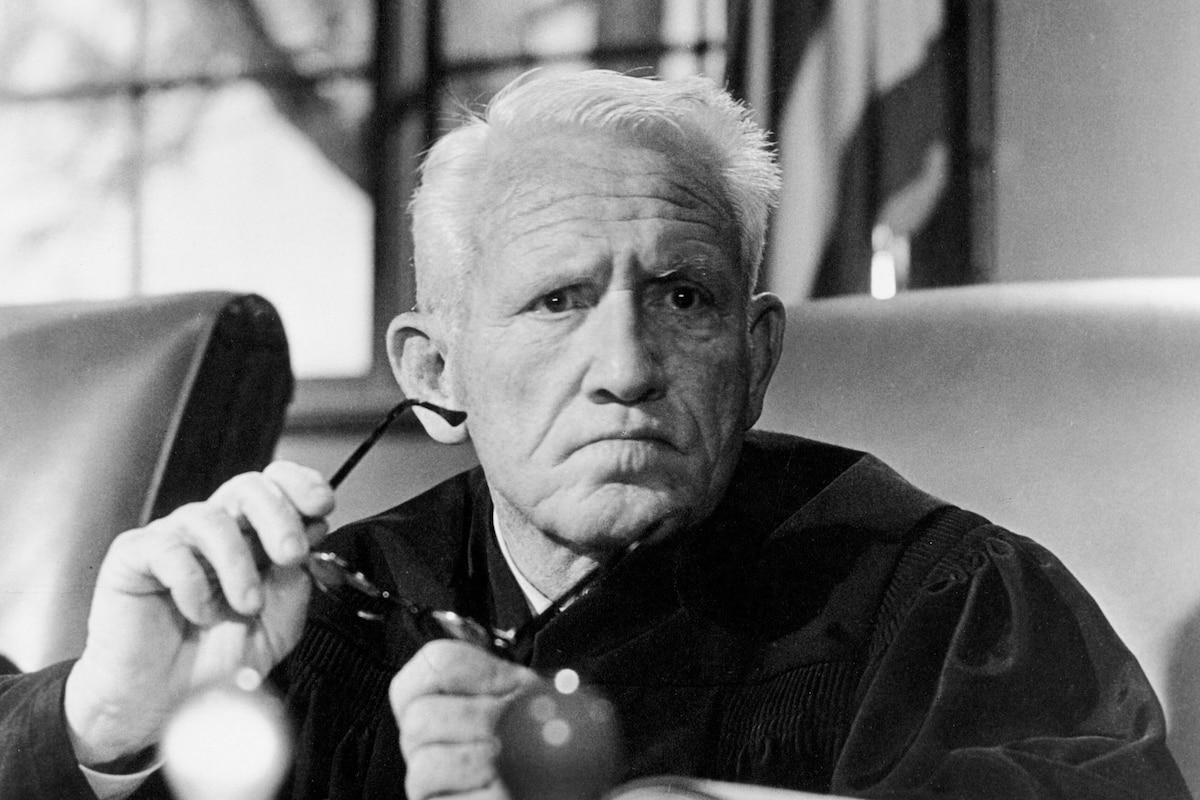

The German press called Spencer Tracy a coward for leaving the Congress Hall, where the film was premiering in West Berlin, before the movie was over. Kramer explained it was due to illness. It may also have been due to Tracy's disgust at Montgomery Clift's drunken behavior at the event.

Maximilian Schell said there was some negative reaction to him in Germany because of his part in this film. "Also people don't like it when one of their own has success in Hollywood," he added.

Despite the controversy it caused in Germany, Judgment at Nuremberg earned more than $5 million on its initial release. The production cost $3 million.

Some gossip columnists found it ridiculous that major stars like Clift and Garland were nominated in Oscar's supporting categories. Louella Parsons said it was like "a bank president reducing himself to the title of bookkeeper in order to get a coffee break," and Sheila Graham suggested the Academy institute an award for Best Star Cameo.

When actress Nancy Walker went to see the film, she got up after Clift's scene and said to a friend accompanying her, "Let's go, David. Nobody's going to beat that."

Garland cried when Kramer telephoned her to say that he, writer Abby Mann, and fellow cast members Richard Widmark and Spencer Tracy stood and applauded after watching her performance for the first time in the rough cut.

Although Garland won neither the Academy Award nor the Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actress (Rita Moreno took both for West Side Story, 1961), the Globes presented her with the Cecil B. DeMille Award for services to the industry.

"If you want to see some real honest-to-goodness acting, you should come to our set...and watch Spencer Tracy and Miss Judy Garland do some real emoting for you." Burt Lancaster to members of the Hollywood Foreign Press Association during production of the film

"We cannot deny the fact, and we do not want to deny it, that the roots of the present position of our people, our country, and our city lie in this factthat we did not prevent right from being trampled underfoot during the time of the Nazi power. Anyone who remains blind to this fact can also not properly understand the rights which are today still being withheld from our people. It will probably be difficult for us to watch and hear this film. But we will not shut our eyes to it. ... I hope that world-wide discussion will be aroused by both this film and this city, and that this will contribute to the strengthening of right and justice." West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt at the premiere of the film, December, 14, 1961

"It was a great privilege to say those words [you wrote]. All I can say is if the lights go out now, I still win." Spencer Tracy, in a telegram sent shortly after the premiere to screenwriter Abby Mann, who kept it hanging on his wall for years after

"I said to myself, who the hell can get any sympathy on the other [German] side after you've seen these [concentration camp] films? And you answered it because you played it with such humanity." writer Abby Mann, talking to Maximilian Schell in 2004 about his performance as the defense attorney

Judgment at Nuremberg was the first time Nazi concentration camp footage was used in a commercial film.

With his Best Actor award for this film, Maximilian Schell became the first performer to win an Academy Award® for a role he originally played on television.

After winning his Oscar®, Schell recalled coming to the U.S. for the first time and telling a customs officer he was an actor. "Good luck," was the official's response. "I can tell him now I had it," Schell said.

Maximilian Schell made his Hollywood film debut in the World War II drama The Young Lions (1958) playing a German officer opposite Marlon Brando, who wanted to play the role of the defense attorney in Judgment at Nuremberg that won Schell his Oscar®.

Maria Schell (1926-2005) was the older sister of Maximilian and already internationally known when he appeared in Judgment at Nuremberg. In America, she had appeared in The Brothers Karamazov (1958), in a part Marilyn Monroe had hoped to play; the Western remake Cimarron (1960); and on television in remakes of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1959), opposite Jason Robards, and Ninotchka (1960). Maximilian Schell said in 2004 that when he won his Academy Award® he thought he would finally be recognized for his own talents and not for being Maria Schell's little brother. However, according to him, in Germany a headline read, "Brother of Maria Schell Wins Oscar®." Schell made a documentary about his sister in 2002, My Sister Maria.

Schell also made a documentary about his Judgment at Nuremberg co-star Marlene Dietrich. The legendary actress, 83 and a reclusive invalid when Marlene (1984) was made, refused to appear on camera and is only heard on the soundtrack. The film won numerous Best Documentary awards, including ones from the New York Film Critics Circle and the National Society of Film Critics, and was nominated for an Academy Award.

Judgment at Nuremberg marked Tracy's eighth Academy Award® nomination. He would be nominated once more, for Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967). He won two years in a row for Captains Courageous (1937) and Boys Town (1938), the second actor to do so; the first was Luise Rainer, who won for The Great Ziegfeld (1936) and The Good Earth (1937).

Marlene Dietrich had not made a film for three years before she accepted a role in Judgment at Nuremberg. From the early 1950s until the mid-1970s, she concentrated more on her highly successful career as a cabaret and concert artist, touring the world with her show, wearing gowns designed to appear daringly sheer by Jean Louis (who did her costumes for Judgment at Nuremberg). After this, her screen appearances were confined to a very brief cameo as herself in Paris When It Sizzles (1964); a filmed record of her concerts, I Wish You Love (1973); and her final performance, heavily veiled, in Just a Gigolo (1978), shortly after an accident and illness ended her live performance career. Dietrich soon became a recluse in her Paris apartment, where she rarely went out or had visitors, preferring to keep in touch with family, friends, and colleagues through frequent and lengthy telephone calls. Dietrich was heard but not seen on film one more time in Maximilian Schell's biographical documentary Marlene (1984). She died in her Paris apartment in 1992 at the age of 90.

In her biography of her famous mother, Maria Riva noted how Dietrich's performance in Judgment at Nuremberg was "a meticulous, brilliant recreation of her mother.... How sad that her most vivid subconscious memory of her mother should be one of stoic self-aggrandizing loyalty to dutyin a black velvet suit."

Judy Garland was scheduled to appear at the London premiere, but after attending the opening in Berlin, she flew to Rome where she collapsed in the Excelsior Hotel due to exhaustion from her very heavy concert tour schedule in 1961 and a serious case of pleurisy.

Although Spencer Tracy greatly admired Montgomery Clift as an actor during the filming of Judgment at Nuremberg ("He makes most of today's young players look like bums."), he was less enthusiastic about his behavior at the Berlin premiere. As screenwriter Abby Mann later recalled, "Monty showed up stoned and drunk out of his mind, jumping on Spence's back. He freaked out in the theater, crawling on his hands and knees between the aisles and screaming out all sorts of crazy things. After Spence got up and left, it crossed my mind that seeing Monty in that advanced state of deterioration might have reminded him of his own drinking problem."

Stanley Kramer's career as a producer began in 1942 and included such films as Champion (1949) and Death of a Salesman (1951). He turned to directing with Not as a Stranger (1955) while continuing to produce, most often performing dual functions on his film projects. His final film as producer-director was The Runner Stumbles (1979). He died in 2001 at the age of 87.

Kramer once said, "If I am to be remembered for anything I have done in this profession, I would like it to be for the four films in which I directed Spencer Tracy." It was his intention to name his son after Tracy, but when the baby turned out to be a girl, he named her after Katharine Hepburn instead.

Judgment at Nuremberg was shot by Hungarian-born Ernest Laszlo, who began his career in silents and worked steadily through 1977, earning eight Academy Award nominations along the way. The first four of these were for Kramer films: Inherit the Wind (1960), Judgment at Nuremberg, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), and Ship of Fools (1965), which brought Laszlo his only Oscar. His final film, The Domino Principle (1977), was Kramer's penultimate production.

Composer Ernest Gold was another frequent Kramer collaborator, totaling ten films together. Gold's most famous screen work was his Academy Award-winning score for Exodus (1960).

William Shatner (TV's Star Trek, Boston Legal), who plays Captain Byers in Judgment at Nuremberg, was one of The Brothers Karamazov (1958) opposite Maximilian Schell's sister Maria.

George Roy Hill was a young director who had achieved success in live television dramas when he was hired to direct Judgment at Nuremberg on Playhouse 90 in 1959. A few years later, Hill was given his first shot at a feature film with the Tennessee Williams adaptation Period of Adjustment (1962). He went on to become the award-winning director of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973).

PROMOTIONAL COPY: Once in a generation, a motion picture explodes into greatness.

by Rob Nixon

Memorable Quotes from JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG

JUDGE DAN HAYWOOD: Hitler's gone, Goebbels is gone, Goering is gone, committed suicide before they could hang him. Now we're down to the business of judging the doctors, business men and judges. Some people think they shouldn't be judged at all. ... No, I think the trials should go on, especially the trials of the German judges.

RUDOLPH PETERSEN (speaking about his forced sterilization): Since that day I've been half I've ever been.

MADAME BERTHOLT: I have a mission with the Americans...to convince you that we are not all monsters.

HAYWOOD: The trouble with you, Colonel, is you'd like to indict the whole country. Now that might be emotionally satisfying to you, but it wouldn't be exactly practical and hardly fair.

COLONEL LAWSON: There are no Nazis in Germany, didn't you know that, Judge? The Eskimos invaded Germany and took over. That's how all those terrible things happened. It wasn't the fault of the Germans, it was the fault of those damn Eskimos!

MME. BERTHOLT: Do you think we knew of those things? Do you think we wanted to murder women and children? ... We did not know!

HAYWOOD: As far as I can make out, no one in this country knew.

MME. BERTHOLT: We have to forget, if we are to go on living.

HANS ROLFE: Do you think I have enjoyed being defense counsel in this trial? There were things I had to do in that courtroom that made me cringe. Why did I do them? Because I want to leave the German people something. I want to leave them a shred of dignity. ... If we allow them to discredit every German like you, we lose the right to rule ourselves forever. Do you want the Americans to stay here forever? ... I could show you pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Thousands and thousands of burned bodies, women and children. Is that their superior morality?

SENATOR BURKETTE: We're going to need all the help we can get [against the Soviets]. We're going to need the support of the German people.

HAYWOOD: Before the people of the world, let it now be noted that here in our decision, this is what we stand for: justice, truth, and the value of a single human being.

ERNST JANNING: Judge Haywood... the reason I asked you to come: Those people, those millions of people... I never knew it would come to that. You must believe it, you must believe it!

HAYWOOD: Herr Janning, it "came to that" the first time you sentenced a man to death you knew to be innocent.

ROLFE: I'll make you a wager. ... In five years, the men you sentenced to life imprisonment will be free.

END TITLE: The Nuremberg trials held in the American Zone ended July 14, 1949. There were 99 defendants sentenced to prison terms. Not one is still serving his sentence.

Compiled by Rob Nixon

Trivia - Judgment at Nuremberg - Trivia and Fun Facts About JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG

by Rob Nixon | January 21, 2010

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM