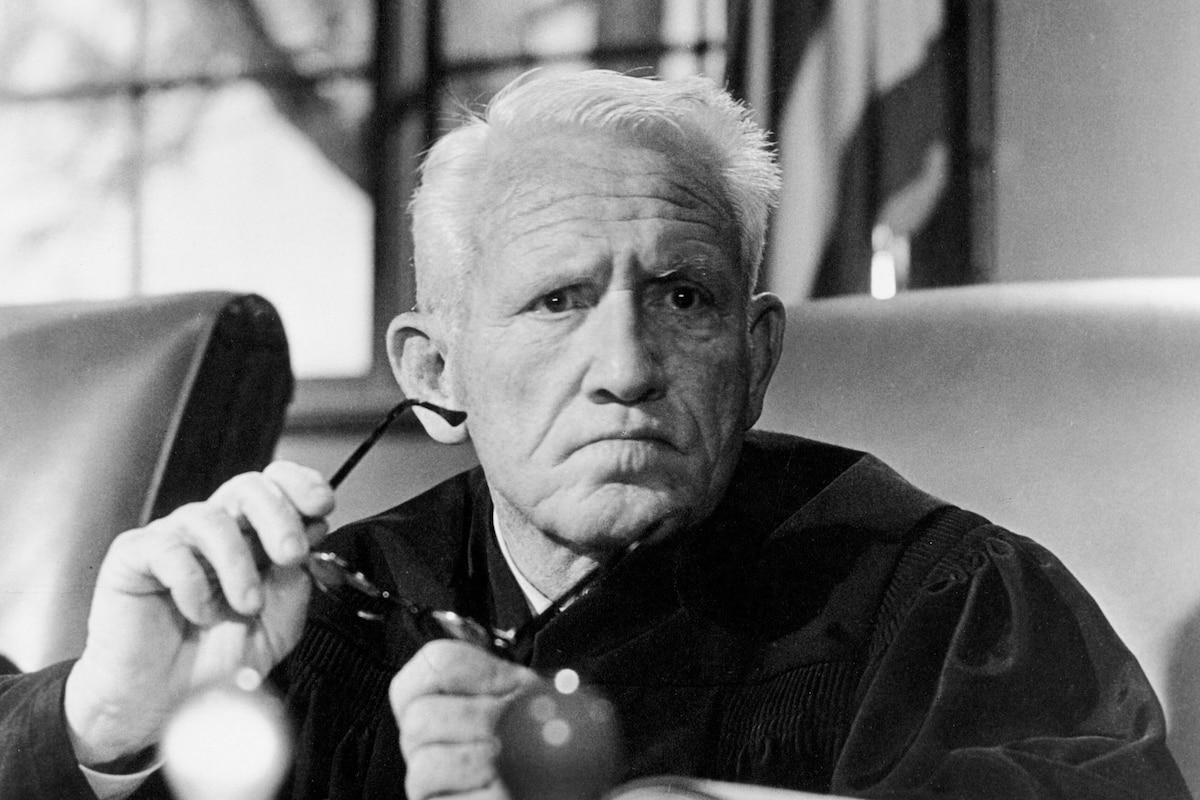

To help boost Judgment at Nuremberg's chances of getting studio backing, promotion and a profitable release, producer-director Stanley Kramer set about assembling an all-star cast, a task made easier by having in Spencer Tracy a universally admired and respected actor that many performers were eager to work with. Noted stars such as Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, and Marlene Dietrich were willing to take smaller roles in the ensemble to be part of a project that, for various reasons, they believed in strongly.

Even though his aim was for bigger names, Kramer decided to cast relative unknown Maximilian Schell on the strength of his performance as defense attorney Hans Rolfe in the television version. Three other players were also retained from the TV production, including Werner Klemperer as one of the judges.

Mann said that Kramer was working with such an experienced powerhouse cast that he had little need to give detailed direction and just let them follow their instincts.

Despite being ill with a kidney ailment and other problems exacerbated by his longstanding alcoholism, Tracy agreed to go to Germany for exterior location shooting and even worked hard when he returned to the studio set in Hollywood. Katharine Hepburn was reportedly with him throughout the production, keeping an eye on him and caring for him. Tracy's biggest fear was that he would not be able to remember his lines. Kramer made special arrangements in the shooting schedule to keep Tracy from getting tired, such as agreeing to a contract stipulation that the actor would finish work promptly at 5:00 every day.

Tracy dropped his "no work after 5:00" rule for Maximilian Schell, staying on the set during shooting of Schell's big summation speech so that he could deliver his lines to Tracy as the presiding judge.

Tracy loved Abby Mann's script and was adamant about his fellow cast members performing it exactly as written, "and that goes for this guy and this guy and this guy," he'd say on the set as he pointed to all the big stars. He complained to Mann angrily that Marlene Dietrich was having Billy Wilder rewrite all her lines. So when she arrived on the set one day with her script marked with "little changes," Mann tore it up on the spot and told her to go out and read her lines in his words. Tracy then got angry with Mann for being too demanding with Dietrich in front of the crew.

Watching Maximilian Schell shoot a scene one day, Tracy said to Richard Widmark, "We've got to watch out for that young man. He's very good. He's going to walk away with the Oscar® for this picture."

Tracy enjoyed playing practical jokes on people and getting the goat of some of his fellow cast members. Entertainment writer Charles Hyams recalls Tracy telling him exactly how much Burt Lancaster was being paid for his role as a repentant German jurist and told Hyams to check with the actor to confirm it. When Hyams asked, Lancaster, who was never known for his sense of humor, was furious while Tracy sat back watching and laughing.

Tracy also had a bit of fun with Abby Mann. One day when Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas showed up on the set, Mann brought him over to meet Tracy. To his embarrassment, Tracy told Mann in front of Douglas, "Take your Communist friends and go to hell." It was only later at lunch that Mann realized Tracy and Douglas knew each other well for years."

Much as he liked to rib others, Tracy didn't always have a sense of humor about himself. When Associated Press reporter Bob Thomas, a longtime friend of Tracy's, visited the set and asked Lancaster jokingly, in reference to the all-star cast, how he was dealing with all the "ham" on display, Lancaster didn't respond and walked away with a shrug. A few days later when Thomas returned to the set and said hello to his old friend, Tracy replied gruffly, "What the hell are you doing here?" He also made nasty comments about the journalist when Thomas tried to speak to other cast members. Attempting to interview Tracy, Thomas was met only with an angry, "I suppose you've come around to talk to the hams." Tracy didn't speak to him for six years after that.

Aside from his occasional off-camera pranks, Tracy took the work very seriously and expected others to do the same. When an actor playing one of the American judges continued to eat a pastrami sandwich between takes, Tracy blew up and said, "How the hell can we be passing judgment on four guys, imprisoning them for life for war crimes beyond comprehension, and knowing all that, how the hell can you munch on that sandwich?"

According to Kramer, a young New York stage actor in a small part held up production at one point. He was trying to understand his motivation in a brief shot which called for him to enter a room, cross to a table, and wait for Tracy to enter to hand him a folder. At 10:15 a.m., after sitting in his dressing room since 9:00 am, waiting to make his entrance, Tracy stormed onto the set and said, "Lookit, you come in the f***ing door and cross the f***ing room and go to the f***ing table because its the only way to get in the f***ing room. That's your motivation."

On the day Tracy gave his 14 minute summation speech, the set at Universal Pictures was packed to the rafters with celebrities and studio executives. Kramer shot Judgment at Nuremberg in a single take, not because he thought breaking it up would necessarily lessen the impact of the words but because he knew he would get the maximum emotional payoff out of Tracy without having to start and stop. To be sure he had the coverage he needed without scheduling a reshoot, Kramer had the speech filmed with two cameras simultaneously from two different angles.

Marlene Dietrich was reluctant to play her role until every detail was ironed out to her satisfaction. She insisted her frequent designer Jean Louis create all her clothes. Dietrich also had Kramer alter the painting of the man who was supposed to be her dead military officer husband because she didn't think he looked dignified enough. Each day she would march onto the set and immediately give orders about how she was to be lighted and where the camera should be placed.

Always in denial about her age and extremely careful to preserve her flawless image, Dietrich had cosmetic surgery (it was not the first time) before shooting began which, accentuated by the lighting, gave her sharp facial angles and a tight mouth that limited her expressions. She was very much displeased when she saw the completed film.

Much of Dietrich's dialogue had to be post-dubbed, purportedly because her voice was too low and thin for sync sound recording.

Judy Garland was cast in the small role of a woman who testifies before the court about her imprisonment in the 1930s for racial pollution because of her friendship with an elderly Jewish man who was subsequently executed for his closeness to her. She was alerted to the part by her business partners Freddie Fields and David Begelman, who learned about it through one of their clients, Marlene Dietrich. When they approached Kramer, he was interested but remained noncommittal, so they continued with plans for an extensive concert tour for the singer-actress. Like everyone in the business, Kramer was aware of her reputation for being difficult and unreliable and her long addiction to drugs. She had not made a movie since A Star Is Born (1954), but when he went to see her concert in Dallas, he was struck not only by the "tremendous emotional range" of her performance but by the fierce adulation she inspired in her audiences. Reasoning that it was only an 18-minute part that would take no more than eight days on the set, he offered her the role for an agreed-upon $50,000. Despite her reputation for being difficult, Garland proved to be punctual, cooperative, and professional throughout the shoot.

Garland had gained considerable weight since her last picture in 1954 (A Star Is Born) and wanted to trim down for the role, but since she was playing a poor German hausfrau, Kramer convinced her not to alter her appearance.

On Garland's first day on the set, cast and crew greeted her with warm and lasting applause. It was a welcome return to films for her, and her mood was further elevated by the lower pressure of acting in a cameo, rather than carrying a picture as she had done in almost every film she made since childhood. Still her joyful attitude made it difficult for her to perform her dark emotional scenes. "Damn it, Stanley, I can't do it. I've dried up. I'm too happy to cry," she said. He gave her a ten-minute break before continuing to great effect. "There's nobody in the entertainment world today, actor or singer, who can run the complete range of emotions, from utter pathos to power...the way she can," Kramer said.

Garland did exhibit some of her old behavior later when she was required to do some retakes on the same day she was scheduled to perform at the Hollywood Bowl. The prospect of ruining her voice before the concert terrified her, and she became hysterical. Kramer rescheduled her scenes, but it still took her friends and handlers four hours to calm her down.

Garland was coached in her accent by a linguist recommended by the German-born actress Uta Hagen.

Another actor with a bad reputation and a disabling substance abuse problem was cast in the other key cameo. Montgomery Clift played a "feeble-minded" laborer who was forcibly sterilized by the Nazis as a young man. Unlike Garland, Clift worked steadily through the 1950s in spite of his addictions and a near-fatal car accident that damaged his handsome face.

One source claims Clift was originally considered for the role of the prosecuting attorney played by Richard Widmark but he chose this cameo instead. "To be an actor is to play any partlarge or smallthat has something important to say," he told columnist Sidney Skolsky. Kramer offered him $100,000 to do the role; other sources say Clift's agents at MCA were sent the script for the part of the laborer and they asked for $200,000his fee on his previous picture, The Misfits (1961)for his seven minutes of screen time. Clift was so eager for the part he offered to do it for expenses only and no salary. "Since it's a single scene and can be filmed in one day, I strongly disapproved of taking an astronomical salary," he explained to the New York Times. "I felt it was more practical to do it for nothing rather than reduce my price or refuse a role I wanted to play."

Clift's deal didn't turn out to be such a reasonable break for the production budget since his expenses included an open tab for him and his friends at the Bel-Air Hotel, chauffeured transportation, and all the liquor he wanted.

When Clift showed up on the Judgment at Nuremberg set, his appearance was rather disturbinghair badly cropped, nervous, uncomfortable, and apparently at the end of an alcoholic benderbut Kramer thought that his condition made him look and speak exactly right for the role.

Since he was only scheduled for five days work (which stretched to ten due to Tracy's illness), Clift decided to avoid the agony of drying out, which he usually did for his other acting jobs. Instead he drank quite openly every moment of the shoot when he was not in front of the camera, dumping out most of the contents of an orange juice carton and refilling it with vodka.

Perhaps fearing he wouldn't be able to perform some of Mann's longer passages of dialogue, Clift asked Kramer if he could change some of the dialogue where necessary. Kramer told him he could have a certain amount of flexibility.

Clift did have difficulty with his lines, cues, and timing and told Kramer he didn't know if he could actually get through the scene. Kramer did his best to reassure him, but it was Spencer Tracy who eventually helped Clift through it. Perhaps drawing on his own years of alcoholism, Tracy spoke to the younger actor with sympathy but with firmness, even relaxing his own dictum about sticking strictly to the script: "Just look into my eyes and do it. You're a great actor and you understand this guy. Stanley doesn't care if you throw aside the precise lines. Just do it into my eyes and you'll be magnificent." Clift spent four days getting through the seven-minute sequence, stumbling through and performing each take differently. At the end of his last take, the set broke out into spontaneous applause. "Monty's condition gave the performance an aura as though it were being shot through muslin, the way the words tumbled out and the disjointed, sudden bursts of lucidity out of a mumble," Kramer said later. "It was classic! It was one of the best moments in the film!" Some film historians and critics have since suggested that Kramer knew exactly what he was doing by casting such broken and erratic performers as Garland and Clift in roles that called for expressions of pain, embarrassment, and terror.

Garland and Clift became close friends during filming. Clift hung around an extra week after his scene was completed, so he was able to sit in the corner and watch Garland do her scenes. (It also greatly inflated his "expenses only" agreement). As she broke down on the stand, he wept openly. When she finished her take, he went over to Kramer, his eyes and cheeks still wet with tears, and said, "You know, she did that scene all wrong."

Burt Lancaster was not the first or even second choice for the role of the judge on trial. Laurence Olivier was originally cast but dropped out to marry Joan Plowright, according to Kramer, and to pursue some theatrical work. Kramer then tried unsuccessfully to get another German for the part (the three other judges were played by German actors). Nevertheless, he and Lancaster worked well together, and the director said later the actor did "one hell of a job making a Nazi into a universal character."

The part of the prosecutor eventually taken by Widmark had been offered to Lancaster earlier, but he turned it down.

Before accepting the role, Lancaster insisted on a guarantee that he would not have to shoot outside Hollywood.

Part of the way through shooting, Lancaster won the Academy Award® for Elmer Gantry (1960). He brought his statuette to the set to show Spencer Tracy.

Kramer wanted to film Judgment at Nuremberg in the original courtroom where the real trials took place, but it was still in use and unavailable to him. He had a mock-up built in the studio, scaled down for greater efficiency in photographing the action.

In order to break up the monotony that often plagues courtroom scenes, Kramer decided to keep the camera moving, which was not always successful in his estimation. At one point, he decided to move it 360 degrees around Richard Widmark during a long speech. It took a lot of rehearsal to choreograph a maneuver that required everyone in the crew to carry cables and equipment around in a circle. "It feels a little indulgent to me now," Kramer said years later. "I'll just have to plead guilty to bad judgment here."

The space between the attorney's box and the witness stand was 40 feet in the real courtroom, which set designers compressed to 28 feet. Nevertheless, actors in the far distance had to have a lot of light cast on them to stay in focus, causing them to greatly perspire.

The exteriors for Judgment at Nuremberg (approximately 15 percent of the footage) were shot on location in Nuremberg and Berlin.

Some sources claim George Roy Hill, who directed the television version, served as an adviser on the set.

by Rob Nixon

Behind the Camera - Judgment at Nuremberg

by Rob Nixon | January 21, 2010

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM