SYNOPSIS

New England Judge Dan Haywood comes to Nuremberg, Germany, to preside over the trial of members of the country's judiciary accused of condemning people under Nazi law, actions that led to the genocide of the Holocaust. With those in the Nazi high command already in prison or dead, Haywood realizes he has a more difficult task - determining the complicity of the more ordinary German citizens, the ones who didn't necessarily formulate the Nazi policies but carried out their orders without question or opposition. On the one side, he has an American military prosecutor who believes in the guilt of an entire nation where no one wants to acknowledge responsibility. On the other side is a German defense attorney who sees far grayer areas; he points out how Allied leaders once praised Hitler and questions the "moral superiority" of a country that would kill thousands of innocent civilians in the service of war, such as in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Haywood also has to contend with growing pressure from U.S. military and political leaders for acquittals in order to gain the support of the German populace in the growing Cold War with the Soviet Union. With all these factors weighing heavily on him, Haywood seeks answers from the people of Nuremberg, notably the aristocratic wife of a German military man executed for war crimes, in an effort to understand what set their country on an unthinkable course.

Producer/Director: Stanley Kramer

Screenplay: Abby Mann

Cinematography: Ernest Laszlo

Editing: Frederic Knudtson

Art Direction: Rudolph Sternad and George Milo

Original Music: Ernest Gold

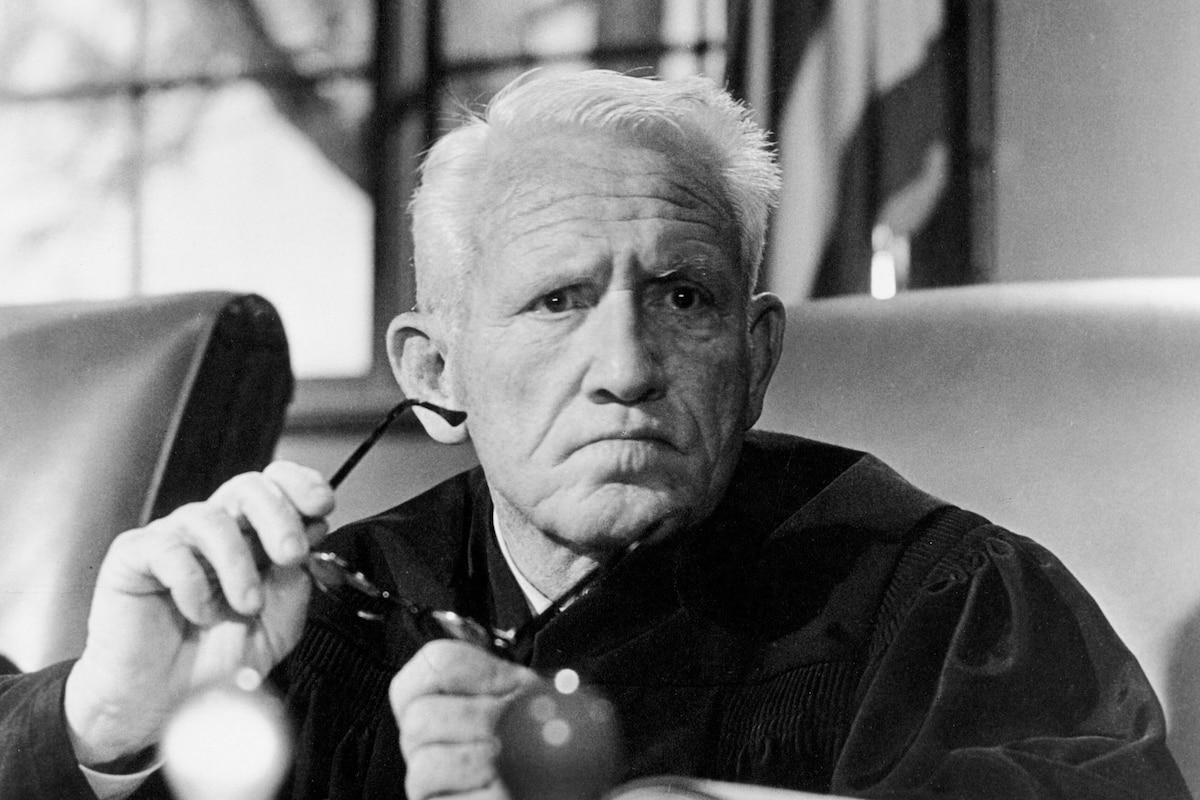

Cast: Spencer Tracy (Judge Dan Haywood), Burt Lancaster (Ernst Janning), Richard Widmark (Col. Tad Lawson), Marlene Dietrich (Mme. Bertholt), Maximilian Schell (Hans Rolfe), Judy Garland (Irene Hoffman), Montgomery Clift (Rudolph Petersen), William Shatner (Capt. Harrison Byers), Werner Klemperer (Emil Hahn).

BW-180m. Letterboxed. Closed Captioning.

Why JUDGMENT AT NUREMBERG is Essential

Producer-director Stanley Kramer's critical reputation has not weathered well over the years; even in his heyday in the 1950s and 60s, he inspired diverging opinions about his importance as a filmmaker, and it was often less than laudatory. In A Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson wrote of Kramer's output: "at worst, they are among the most tedious and dispiriting productions the American cinema has to offer." The best Andrew Sarris could say, in his landmark work on auteur theory, The American Cinema (Dutton, 1968), was "he has been such an easy and willing target for so long that his very ineptness has become encrusted with tradition." With such a drubbing, one would have expected Kramer and his work to have long since fallen into deep obscurity. Yet the films, which drew the participation of some of the finest talents in Hollywood, both in front of and behind the camera, continue to garner interest and inspire debate.

The reason may have to do with Kramer's standing as what Andrew Sarris called "the most extreme example of thesis or message cinema." Even those who slammed Kramer for a lack of cinematic artistry have noted his persistence and willingness to risk all in taking on what were once daring or controversial subjects: racism in The Defiant Ones (1958), nuclear holocaust in On the Beach (1959), censorship and the intolerance of fundamentalism in Inherit the Wind (1960), interracial marriage in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967). The war crimes trials held in Germany after World War II, particularly those of the judges who carried out the most extreme Nazi laws against innocent victims, was first dramatized on live television in Abby Mann's penetrating script. It was a subject tailor-made for Kramer, and he threw himself into it despite the indifference of the studios and the general feeling that, in an era when Germany was an important ally against Soviet expansion, this was a subject better left untouched. He may not have been the critics' darling, but few directors at the time could have forged ahead with such a project. Along the way he gathered a powerhouse cast and award-winning production team, proving that more than one person had ample faith in Kramer.

At the top of that list was Spencer Tracy, by 1961 the Grand Old Man of American cinema, and the actor of his generation most respected by audiences and colleagues alike. Having recently received his seventh Academy Award nomination for Kramer's Inherit the Wind, the aging and ill Tracy jumped at the chance to work with the man he decided would be his sole director for the remainder of his career. Not a bad endorsement for Kramer, and for Tracy it was a guarantee of roles that would add to his carved-in-stone image as the solid, decent, liberal-minded American. His Judge Dan Haywood in Judgment at Nuremberg was perhaps the apotheosis of that image.

Kramer's shrewd casting also added to the film's appeal in the performances of Judy Garland and Montgomery Clift as the two key witnesses in the trials, ordinary citizens whose lives were shattered by the Nazi regime. The two performers were still young when they appeared in this movie - she was not quite 40 and he was almost two years older - but their looks and the wounded exhaustion of their demeanors spoke volumes about their tumultuous private lives. So much of what audiences remember about this film comes from these two Oscar®-nominated cameos, totaling scarcely a half hour of screen time, as the raw emotionalism of two respected but famously self-destructive actors brought an eerie resonance between their off-screen realities and the characters they portrayed.

Added to all this was the casting of Marlene Dietrich in an iconic role near the end of her long career; the young Maximilian Schell, breaking through to international fame with his Academy Award® performance; and the participation of such major stars as Burt Lancaster and Richard Widmark. But beyond the work of the cast, what makes Judgment at Nuremberg essential viewing? Certainly Abby Mann's script deserves much of the credit by providing a structure and tone that not only fosters moral contemplation but ample opportunities for dramatic conflict. And the Motion Picture Academy recognized the steering contributions of a host of very experienced and creative talents behind the camera. Nevertheless, critical opinion of the film varies greatly.

There are those who praise its thematic intentions - and Kramer's courage in going after an unpopular subject based on highly unpleasant realities - while pointing out its failures purely as cinema - not least of which is excessive length and some flashy but pointlessly ineffective camerawork, a shortcoming even Kramer admitted. Ultimately, what makes Judgment at Nuremberg worth seeing and a notable addition to film history is its status as the supreme example of the type of cinema Stanley Kramer represented and strove for throughout most of his career, films with "something to say." With its all-star cast and its lofty ambitions, it is the Grand Hotel (1932) of message movies.

by Rob Nixon

The Essentials - Judgment at Nuremberg

by Rob Nixon | January 21, 2010

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM