The Producer would like to thank

The Lord Summerisle and the people of his island

off the west coast of Scotland

for this privileged insight into

their religious practices and for their

generous co-operation in the making of this film.

With this canny opening text, the makers of the British thriller The Wicker Man (1973) quickly establish that their startling tale takes place in the present day and lend it a seeming verisimilitude. Over the opening credits we see a sea plane approach the island, and after some jostling to come ashore, Police Sergeant Neil Howie (Edward Woodward) informs the dock locals that he has received an anonymous letter informing him about a girl, named Rowan Morrison, who has gone missing from the island. The islanders deny even knowing the girl, and Howie proceeds with his investigation. Considering himself a righteous, Christian man, he is shocked to witness pagan rituals being carried out by the townsfolk; young boys sing merrily about impregnation while dancing around a maypole, and young girls jump naked over a bonfire as they worship the gods of the earth, sun, and elements. While interviewing people about Rowan's disappearance, Howie is tempted by the provocative sexuality of the landlord's daughter Willow (Britt Ekland), and has disagreements of conscience with schoolmistress Rose (Diane Cilento), and the leader of the community, Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee). Howie eventually comes to suspect that the missing girl is being hidden away in anticipation of a May Day rite of human sacrifice to appease the gods.

The Wicker Man achieved instant cult status with a proclamation in Cinefantastique magazine (in a 1978 issue-length article by David Bartholomew) calling it "the CITIZEN KANE of horror films." Hyperbolic to be sure, but at first glance the genre classification may seem too limiting - the movie is literate and also functions as a mystery, a police procedural, and a thriller, while its intellectual script touches on history, theology, religion, and many aspects of the human condition. Yet, screenwriter Anthony Shaffer asserted that, in fact, "The Wicker Man is a horror film, if only because of its horrific ending." Shaffer qualifies the term, asking "What is a horror film? It's Christopher Lee with those silly teeth in rushing around through papier-mache corridors chasing nubile ladies... I really think we should be finding new names for these things, because 'horror' implies second-rate bits of crap."

Shaffer had established his reputation with the 1970 stage play Sleuth and the screenplay for the 1972 adaptation starring Laurence Olivier and Michael Caine. He had also written the screenplay for Frenzy (1972), directed by Alfred Hitchcock. As Shaffer elaborated to Cinefantastique, "one of the things that works so well in The Wicker Man is that we took reasonable trouble to make it perfectly contemporary; the people could wear suits and didn't run around in old cowls or something, which I often find takes away from the horror of the situation. ...But you can find just as much horror on High Street with supermarkets and chemist shops, in the sunlight, if you have a really good story."

The story takes the form of a puzzle; not surprising for the game-loving Shaffer, but at its core it deals with a clash of beliefs, personified by the characters played by Woodward and Lee. It was plotted by Shaffer and his friend Robin Hardy; the two had worked together for years for a firm in England producing documentaries and commercials for French and British television. Shaffer showed the screenplay to Christopher Lee, who had wanted to play the leading role of a priest in an earlier, then-unproduced project of Shaffer's called Absolution (Richard Burton played the part when that film was made in 1978). Lee and Shaffer found a sympathetic producer, Peter Snell, who in turn persuaded British Lion to put up the production costs. The Wicker Man was budgeted for $750,000, and shot for seven weeks in many locations in Scotland. Filming was largely uneventful, but it did prove to be unseasonable. The story is set in the Springtime, a crucial point, but filming took place in October and November. Trees and plants in camera range had to be dressed with false blooms, and the cast had to suppress the chattering of teeth from the cold, especially in windswept cliffside scenes.

Because music was so important to the pagan rites that the film depicts, it was decided to prerecord all of the soundtrack material prior to filming. Paul Giovanni only had six weeks to research, compose and record the material, much of which was drawn from centuries-old folk tunes. For example, "Gently Johnny", the song that accompanies Britt Ekland's ritualistic nude dance of seduction, combines the lyrics from three separate folk songs. Songs are used with almost every rite, celebration, and proccession in the film, and while traditional "mood" scoring is absent, the production team realized that the use of songs would be a delicate balance, and that too much emphasis on music and singing would tilt the film into a musical.

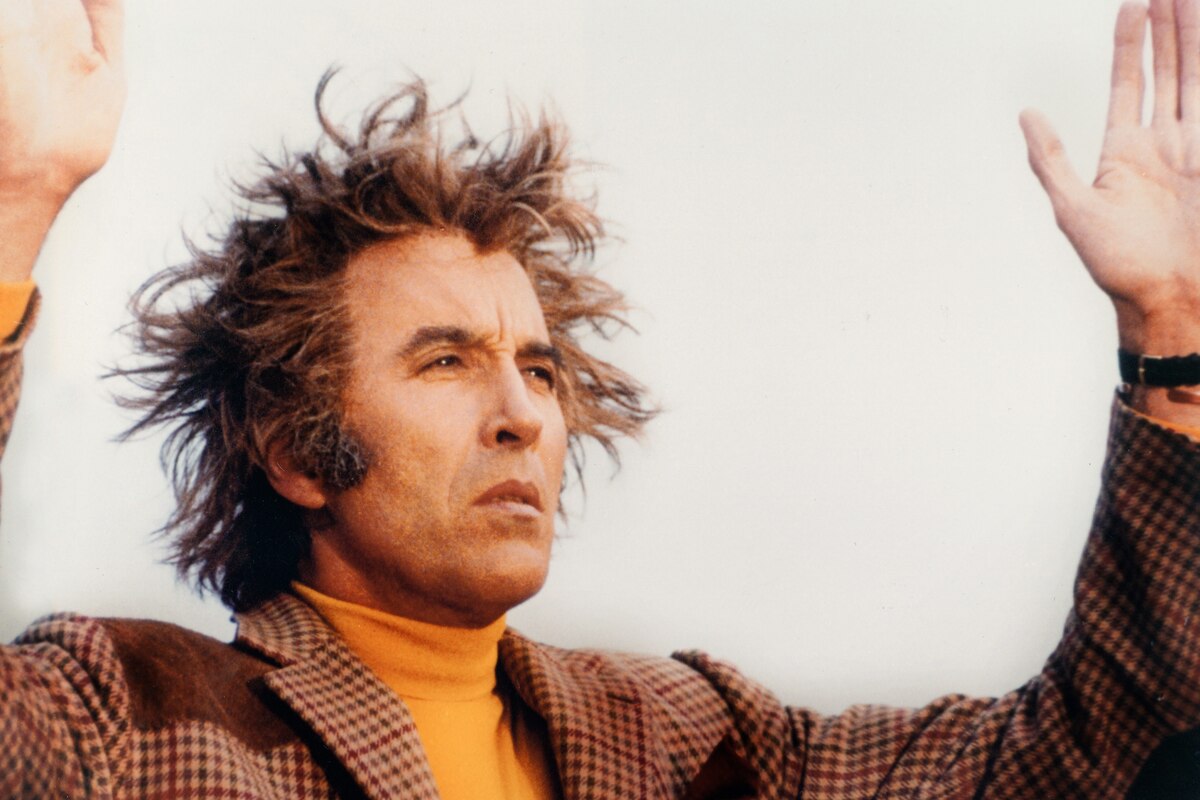

Actor Christopher Lee has long described his role as Lord Summerisle as the favorite of his career. Shaffer wrote the part with Lee in mind, and the actor later said that "...Summerisle is an amalgam of many roles I have played onscreen. Figures of power, of mystery, of authority, of presence. There is quite a lot of my natural delivery in the way Summerisle's dialogue was written... While being genuine, the character had to carry the sense that something was not quite right in that village, and you can't quite put your finger on it. Something is going to happen, but it was so cleverly written, that everyone was charming and normal, even Summerisle, although he's really quite bizarre."

The post-production fate of The Wicker Man has become one of the legendary tales of woe that point out an industry that is too often blind to art. After production wrapped, the film went into editing at Shepperton Studios. According to Giovanni, the editor, Eric Boyd-Perkins, was "a very dull man" who didn't understand the film and found elements of it "disgusting." He turned in a 102-minute cut that satisfied Hardy and Snell, although Christopher Lee was displeased, saying that "...so much magnificent dialogue and meaningful story elements had been removed." The film would end up on the receiving end of more abuse and neglect, however. Before the 102-minute version could be properly exhibited, British Lion changed hands, a new regime was brought in, and the film was taken away from the producer and director. The new man in charge had no interest in releasing the film in Britain, but held out some hope that he could sell it in America. To that end, he sent the film to legendary low-budget producer and distributor Roger Corman. Corman put in a low bid for the rights but also sent a detailed analysis of the film, detailing the cuts he would make to render the film more palatable to American audiences. Consequently, the film was cut to between 87 and 88 minutes. Several key scenes of character development were shortened or eliminated, and the story structure was drastically changed; in the new cut Howie's stay on the island was shortened from two nights to just one. The film, in this state, was finally released in Britain as the lower half on a double bill with Nicholas Roeg's Don't Look Now (1973), and only during that film's run in the secondary houses. All of the principal participants were shocked at the shortened version; Lee said that "...the film was just butchered, it was just outrageous. It was in a form that some of it didn't make sense." Nevertheless, Lee lobbied all of the critics he knew to go and see the film. By the following year, Warner Bros. had acquired the film as part of a package and it played a few dates in America to meet tax requirements, then it was shelved. Virtually the only review that The Wicker Man received during its American run was in Variety - a rave in which they said "Anthony Shaffer penned the screenplay which, for sheer imagination and near-terror, has seldom been equaled."

Unfortunately, the 102-minute version of The Wicker Man could only be reconstructed, years later, with inferior video elements that Roger Corman still had in his possession. The fate of the original prints and negative trims has entered into the unfortunate folklore of Lost Movie Footage: incredibly, the reels that British Lion threw out ended up as concrete filler for a freeway project.

Even in the 88-minute version, The Wicker Man retains its power to intrigue, shock, and challenge conventional precepts. As director Hardy told Cinefantastique, "...everything you see in the film is absolutely authentic. The whole series of ceremonies and details that we show have happened at different times and places in Britain and Western Europe. What we did was to bring them all together in one particular place and time." Hardy spent months researching pagan traditions and found it ironic that "...people do these things today and [don't] know why they do them. We call them 'superstitions.' There are millions of people who know nothing about the Golden Bough who will... 'touch wood.' Or won't walk under ladders. They all have profoundly important and real origins in pagan belief." As Christopher Lee said about the film's approach to Christianity, "The Wicker Man is not an attack on contemporary religion but a comment on it, its strengths as well as its weaknesses, its fallibility, that it can be puritanical and won't always come out on top. Even the Christian religion is based on the execution and sacrifice of one man. In that respect, there's no difference at all."

The Wicker Man was given a needless, Americanized remake in 2006, written and directed by Neil LaBute, which starred Nicolas Cage as the hapless protagonist, now a California motorcycle cop perplexed by a matriarchal pagan society. More intriguing is a semi-sequel, in production as of this writing, to be called The Wicker Tree (aka Cowboys for Christ), which is being directed by Robin Hardy and will feature Christopher Lee in a Summerisle-type role as Sir Lachlan Morrison.

Producer: Peter Snell

Director: Robin Hardy

Screenplay: Anthony Shaffer; David Pinner (novel "Ritual," uncredited)

Cinematography: Harry Waxman

Art Direction: Seamus Flannery

Music: Paul Giovanni

Film Editing: Eric Boyd-Perkins

Cast: Edward Woodward (Sergeant Howie), Christopher Lee (Lord Summerisle), Diane Cilento (Miss Rose), Britt Ekland (Willow), Ingrid Pitt (Librarian), Lindsay Kemp (Alder MacGreagor), Russell Waters (Harbour Master), Aubrey Morris (Old Gardener/Gravedigger), Irene Sunter (May Morrison), Walter Carr (School Master), Ian Campbell (Oak), Leslie Blackater (Hairdresser), Roy Boyd (Broome), Peter Brewis (Musician)

C-88m.

By John M. Miller

The Gist (The Wicker Man) - THE GIST

by John M. Miller | September 02, 2009

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM