In the first five years of the 1960s, low-budget impresario Roger Corman directed a whopping ten costume horror films in the fog-filled soundstages of American International Pictures (among them the Poe-themed House of Usher [1960], Tales of Terror [1962], The Raven [1963], and The Tomb of Ligeia [1964]). To liberate himself from the historical horrors, he devoted the latter half of the decade to exploring more contemporary thrills. The Wild Angels (1966) exploited the widespread fear of and fascination with motorcycle gangs, and gave him his first opportunity to work with actors Peter Fonda and Bruce Dern. Once The Wild Angels was underway, Corman decided to dissect another controversial social phenomenon.

"Like the Angels, and their bikes, the drug subculture was in the headlines," Corman recalled in his memoirs, How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime, "LSD, grass, hash, speed, the drug and hippie movement, dropping out, tuning in, free love -- it was all part of a pervasive 'outlaw' anti-Establishment consciousness in the country during the Vietnam era. More and more 'straight' people were dropping out and 'doing their own thing.' I wanted to tell that story as an odyssey on acid."

Before embarking on the shoot of The Trip (1967), Corman (at Fonda's urging) decided to experiment with LSD. To the wary public, Corman claimed the experience "had taken place under strict medical supervision, with a stenographer on hand to record the episode." In reality, Corman organized an informal road trip to the seaside cliffs of Big Sur, where almost all the cast and crew dropped acid -- in shifts. "We finally ended up with almost the equivalent of a motion picture schedule as to what time each person would take it because I didn't want to have something where everybody was zonked out on LSD," Corman recalled, "We had a few people who were straight while the other people are on LSD. And then when the other people came off the LSD and were straight again, then the other group took the LSD." There was no medical supervision, and the stenographer was Corman's story editor and assistant, Frances Doel.

For a while, Corman could feel none of the drug's effects. "I decided to lie down," he wrote in his memoirs, "I spent the next seven hours face down in the ground, beneath a tree, not moving, absorbed in the most wonderful trip imaginable."

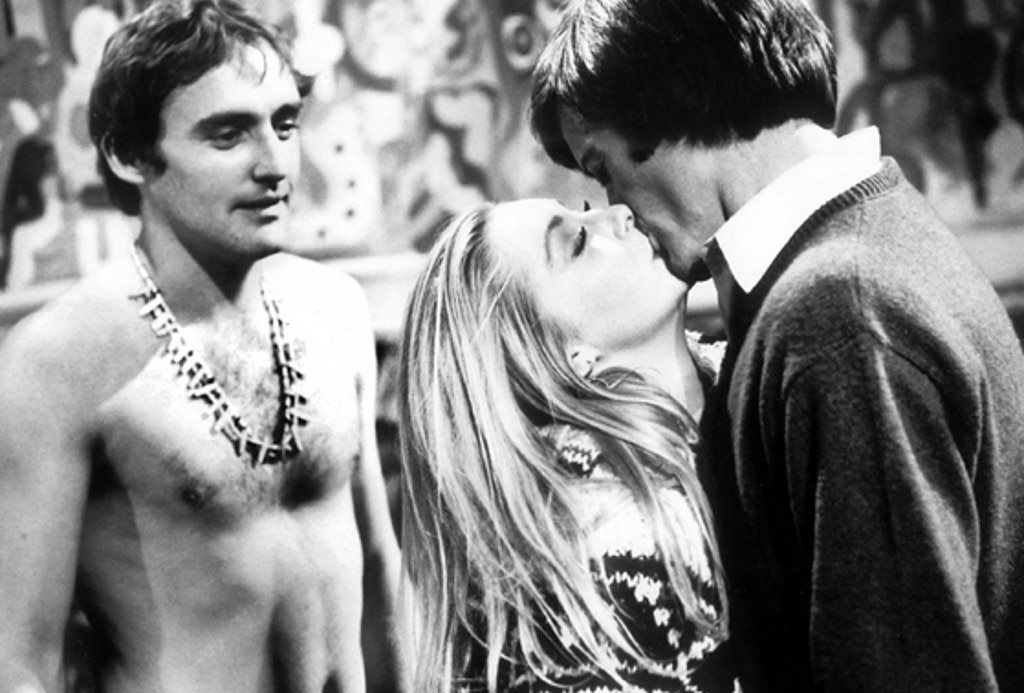

Armed with his first-hand experience, Corman set out to capture the psychedelic experience on film. Penned by actor-turned-screenwriter Jack Nicholson, the story revolved around Paul Groves (Peter Fonda), a disenchanted director of television commercials who is on the brink of divorce from his wife Sally (Susan Strasberg). He meets up with his friend John (Bruce Dern), an LSD guru of sorts, who shepherds him through the process of a hallucinatory trip. At a hippie pad presided over by Max (Dennis Hopper), they score several capsules of lysergic acid diethylamide and take it back to John's place. Under John's careful guidance, Paul drops acid and embarks on a series of unpredictable psychic journeys, frequently pursued in his mind by two hooded figures on horseback.

In time, Paul finds it increasingly difficult to distinguish between hallucination and reality. After a momentary freak-out in a coat closet, he has a vision of John slumped dead in a chair. Paul flees the house and rediscovers the world through kaleidoscope eyes: a suburban home, Sunset Boulevard, a frenzied nightclub called the Bead Game, a laundromat, and eventually Max's commune. He hooks up with Glenn (Salli Sachse), a blonde whom he had previously met at the hippie pad, and caps off his psychedelic journey with a moment of sexual awakening.

The highlights of The Trip are the visual effects employed to graphically render Paul's hallucinations. A cinematic funhouse unfettered by the laws of narrative logic, The Trip employs a wide variety of effects, most of which were achieved "in-camera," rather than through post-production processes. So impressive were the achievements of Gardiner, Beck, and Daviau (under unthinkable budgetary restraints), that American Cinematographer devoted a cover story to the film's production.

Upon its completion, AIP was worried that The Trip painted a too rosy picture of the LSD experience, even though Corman had been careful to depict some of the drug's less enjoyable effects. Once Corman had moved on to his next project, AIP attempted to dilute the film's message with a warning. An introductory title scroll was added which characterized the film as a serious examination of a dangerous social ill (rather than a non-judgmental depiction of one man's drug-induced odyssey of self-discovery). AIP also added an optical effect at the end of the film, superimposing a graphic of shattered glass over Paul's head as he rises the next morning. "Everyone -- Jack, Bruce, Peter, Dennis -- objected along with me. It was the wrong message," Corman recalled, "I was behind that message all the way. So, apparently was the public. The Trip took in well over $6 million in rentals. We were clearly on to something here."

Two years later, the drug use of The Trip would be combined with the bikerdom of The Wild Angels and the result was Easy Rider, which reunited Fonda, Hopper, and Nicholson, and revolutionized the counter-cultural American independent film.

Director: Roger Corman

Producer: Roger Corman

Screenplay: Jack Nicholson

Cinematography: Archie R. Dalzell

Production Design: Leon Ericksen

Music: The American Music Band

Cast: Peter Fonda (Paul Groves), Susan Strasberg (Sally Groves), Bruce Dern (John), Salli Sachse (Glenn), Dennis Hopper (Max), Barboura Morris (Flo), Luana Anders (Waitress), Dick Miller (Cash).

C-85m.

by Bret Wood

The Gist (The Trip) - THE GIST

by Bret Wood | August 20, 2008

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM