The name of Hubert Cornfield (1929-2006) does not loom large over Hollywood. In a 20-year career from 1955 to 1975, he directed only a dozen films and TV episodes. Born in 1929 in Istanbul to a Fox movie executive father, he was raised in France, where he returned for three final projects after his Hollywood career crashed in 1968 on the French location of the kidnap film, The Night of the Following Day, due to arguments with the star Marlon Brando. (Richard Boone, who played the psychotic member of the gang, finished shooting it.) But Cornfield, who began as a graphic artist, had a distinctive eye, and mastered his craft. A handful of his low-budget, noir-tinged genre exercises stand up today, still surprisingly vivid, recalling Noel Coward's character in Private Lives (1931), remarking on the potency of cheap music.

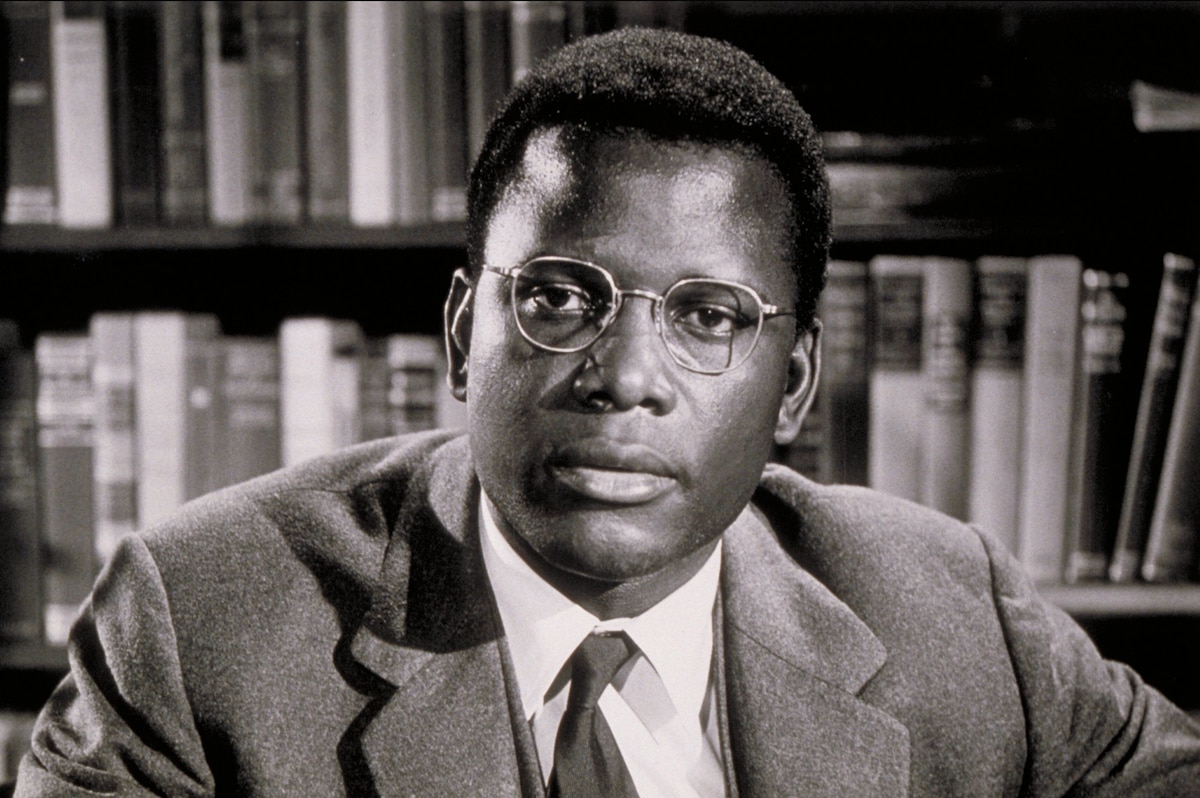

Thus we're still struck by the femme fatale sinking into quicksand in Cornfield's Lure of the Swamp (1957), by the bold, ingenious gold heist scheme in Plunder Road (1957), by Edmond O'Brien's voice impersonating a dead businessman over a phone to grab the latter's assets in The 3rd Voice (1960), and by Mercedes McCambridge's exploited faith healer in Angel Baby (1961). Cornfield peaked with Pressure Point (1962). It's the sort of film that could have and has capsized many a director. But it's too intelligent to settle for exploitation formulas. A message film about reason and high-mindedness staying the course until idealism can overcome destructive hate, it pits Sidney Poitier's prison psychiatrist against Bobby Darin's conflicted, racist, hate-filled Nazi supporter, imprisoned for sedition in 1942. It's told as a long central flashback, framed by Poitier's efforts to keep a frustrated younger doctor Peter Falk on the job when the latter wants off a difficult case involving a hostile patient.

Stemming from psychiatrist Robert Lindner's immensely popular best-selling casebook, The Fifty-Minute Hour (1954), it's fully immersed in Hollywood's decades-long infatuation with pop psychology. When Darin's antagonistic, scornfully contemptuous inmate is sent to Poitier and only agrees to be treated as a means of purging the nightmares that keep him from sleeping, it doesn't take long for the doc to identify daddy issues as the cause of the prisoner's unease. We see Darin's character in a surrealistic flashback within a flashback, as a powerless boy with a weak victim mother and a brutal, rejecting butcher father. Not surprisingly, he seeks to identify with the power represented by his father hence his lashing out at Jews and African-Americans. At the same time, he's conflicted by his guilt feelings over wanting to kill his father. No wonder his dreams of a helpless self, about to be washed away down a giant sink, switch over to his father being the one about to go down the drain, Incredible Shrinking Man-style.

The dream sequences involving helplessness and rage are rendered simply, with arresting urgency. But the purging of the hatemonger's nightmares doesn't clear up the ingrained hatred projected against Jews and African-Americans and anyone over whom the twisted abusee turned abuser thinks he has, or can get, the upper hand. Cornfield gets around the dulling potential of the message film in a startling sequence, ugly and chilling, in which Darin's hater turned thug uses a gang of construction workers under his sway to vandalize a bar, then humiliate and debase the bar owner and his wife in a fashion so hair-raising it still makes us squirm. As it proceeds, and the terrorizing gang's excesses grow more and more sadistic, we realize we're watching an analogue of the appalling rise of Hitler, with tic-tac-toe graphics standing in for swastikas. The sequence rises to the power of nightmare. Later, in the unlikely event we didn't get it, he replicates the 1938 Krystallnacht pogrom, with vandals trashing a kosher butcher shop and take that, daddy! throwing an animal carcass into the street to rot.

Now able to sleep at night, the convict veneers his unruly behavior enough to be considered eligible for parole. Poitier's shrink, knowing the problem isn't really solved, argues against it. The doc undergoes his own personal crisis when he feels the American Nazi's racist taunts and needlings getting to him, realizes the guy's destructive potential scares him, and wants out. Throughout, one's sympathy gravitates to Poitier, as much for the saintly personas he was shoved into during much of his movie career as well as his character's predicament here. Inspirational he inarguably was, and remains, yet he seems in retrospect to have been shackled to undue politeness, reasonableness and decorum in the name of racial harmony. And so it is here.

It's Darin who really gets to us. The erstwhile pop singer was acclaimed for his portrayal of a troubled patient of Gregory Peck's military hospital psychiatrist in Captain Newman, M.D. (1963). But he's at his most indelible and unforgettable as the damaged, dangerous, sly, rage-filled gutter rat in Pressure Point. Stanley Kramer said, "I think he [Darin] was a wonderful actor. I think he felt pain. And when you feel pain and frustration and some failure as well as success, which he had an inordinate amount of, I think those things make a person who has talent a person who has much greater talent. I look at that performance and I think to myself, 'Yeah, I sure didn't make any mistake there,' and however the film may have failed or succeeded, his contribution was major." (from Borrowed Time: The 37 Years of Bobby Darin by Al Diorio, Running Press).

At the end, Poitier is lumbered with the obligatory upbeat pronouncement, "This is my country. You are still going to lose." But the knowing gleam in Darin's eye tells us his disaffiliated loser doesn't think so. Given its budgetary exigencies, Pressure Point could easily have settled for being a bit of efficient soapboxing. But it's too intelligent to succumb to easy consolations. Which is why its intelligent, unflinching acknowledgment of the power of evil still can jolt us.

Producer: Stanley Kramer

Director: Hubert Cornfield

Screenplay: Hubert Cornfield, S. Lee Pogostin; Robert Lindner (story "The Fifty-Minute Hour")

Cinematography: Ernest Haller

Art Direction: George Webb

Music: Ernest Gold

Film Editing: Frederic Knudtson

Cast: Sidney Poitier (Doctor), Bobby Darin (Patient), Peter Falk (young psychiatrist), Carl Benton Reid (Chief medical officer), Mary Munday (bar hostess), Barry Gordon (boy patient), Howard Caine (tavern owner)

BW-90m. Letterboxed.

by Jay Carr

Sources:

"In Memoriam: Hubert Cornfield," by Alan K. Rode, Film Monthly, July 11, 2006

"Beyond the Imaginary Line: Hubert Cornfield, 1929-2006," by F.X. Feeney, L.A. Weekly, July 12, 2006

Borrowed Time: The 37 Years of Bobby Darin by Al Diorio, Running Press

IMDb

Pressure Point

by Jay Carr | January 11, 2008

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM