Even though Billy Wilder was quite content with Ray Milland as the lead in The

Lost Weekend, his first choice for the role had been Jose Ferrer. Wilder had just seen the actor as Iago opposite Paul Robeson in a Broadway production of Othello. But because the project was so much against the grain of Hollywood's usual fare, Paramount said audiences would reject the lead character, not to mention the movie, if he was not played by a well-known actor. So Milland was chosen over the lesser-known Ferrer.

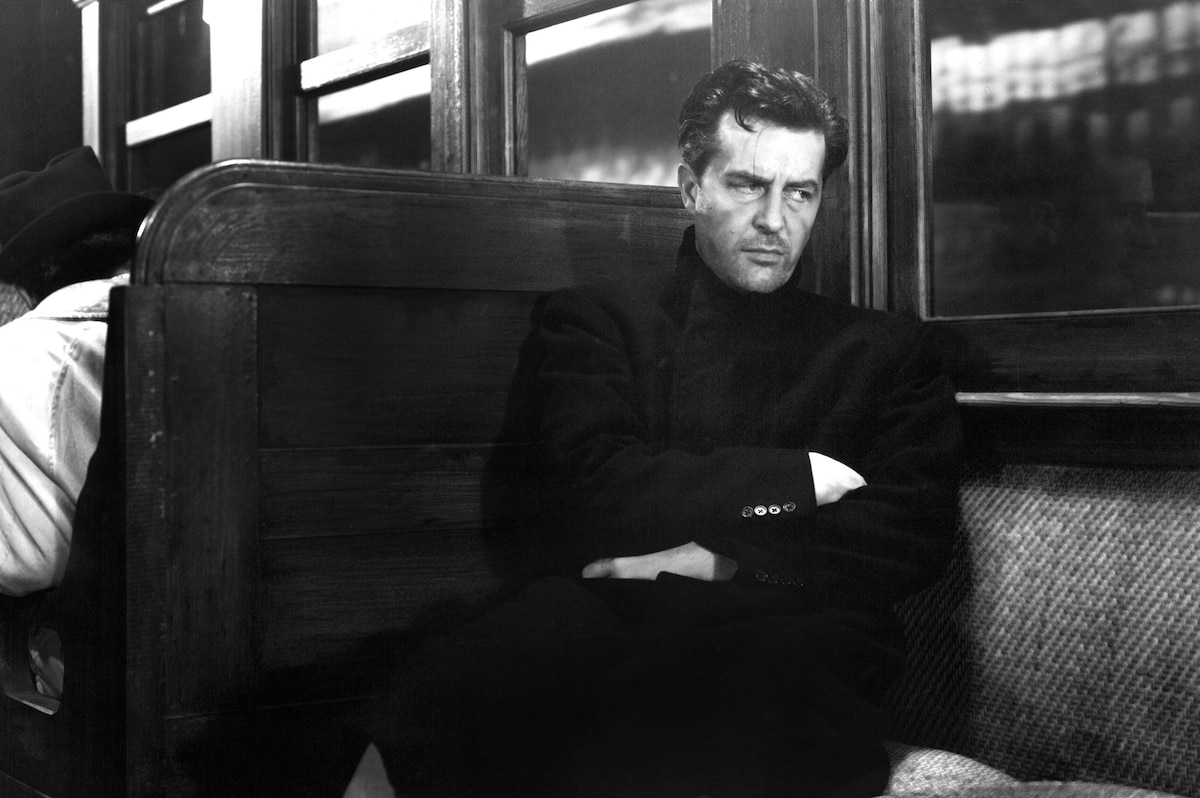

Ray Milland had been a popular matinee idol for several years in Hollywood, making his mark in romantic comedies and adventure films, so the decision to cast him in The Lost Weekend was a surprise to many, especially him. Milland was given the Charles Jackson novel to read by Paramount chief Buddy De Sylva, with a note attached reading: "Read it. Study it. You're going to play it." Milland read it, and was struck by its dramatic dimensions as a social document, but he could not see much of a film in the bleak story, nor could some of his friends and associates. If Milland took on the role, they felt he would be committing professional suicide. On top of that, Milland doubted he had the acting chops to pull it off, but his wife encouraged him to take a chance. Additionally, Milland was tempted to star in the film because Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett were currently riding high from previous successes. So the actor finally agreed to appear in what would become his most famous role.

To achieve the gaunt, haggard look of a drunk on a whopper of a bender, Ray Milland went on a crash diet of dry toast, coffee, grapefruit juice and boiled eggs, and subsequently took off many pounds. Not a heavy drinker, Milland even tried getting drunk, but he usually ended up on his knees in a bathroom.

Ray Milland actually checked himself into Bellevue Hospital with the help of resident doctors, in order to experience the horror of a drunk ward. Milland was given an iron bed and he was locked inside the "booze tank." He recalled in his autobiography, Wide-Eyed in Babylon, "The place was a multitude of smells, but the dominant one was that of a cesspool. And there were the sounds of moaning, and quiet crying. One man talked incessantly, just gibberish, and two of the inmates were under restraint, strapped to their beds." That night, a new arrival came into the ward screaming, an entrance which ignited the whole ward into hysteria. With the ward falling into bedlam, a robed and barefooted Milland escaped while the door was ajar and slipped out onto 34th Street where he tried to hail a cab. When a suspicious cop spotted him, Milland tried to explain, but the cop didn't believe him, especially after he noticed the Bellevue insignia on his robe. The actor was dragged back to Bellevue where it took him a half-hour to explain his situation to the authorities before he was finally released.

After director Billy Wilder learned of Milland's nightmare, he gleefully employed the same ward for his Bellevue scenes. Of course, the administration at Bellevue was not happy with the negative depiction of the hospital and vowed never to cooperate with Hollywood again. In fact, director George Seaton ran into a brick wall when he wanted to use Bellevue for scenes in Miracle on 34th Street (1947). Said Seaton, "The hospital manager practically threw me out because he was still mad at himself for having given Wilder permission to shoot at the hospital."

Milland's extracurricular research once landed him in an embarrassing spot. During his trek down Third Avenue to pawn his typewriter, Milland, who had perfected a deathly-ill appearance for the role, stopped to look into a window. At that moment, two friends of Milland's wife spotted him and mistook him for a real drunk. Both friends dutifully reported back to their Hollywood contacts that Ray Milland was drinking himself to death. Gossip columns soon placed items in the West Coast papers reporting the news tidbit, prompting Milland's wife to call him, telling him that he had better set the record straight. Paramount's publicity department was soon working overtime trying to correct the misunderstanding.

In an effort to the make the unrelenting story more bearable, Brackett and Wilder added a love interest for Don Birnam in the script. Katharine Hepburn was offered the relatively small role and her curiosity was piqued, but the timing was all wrong, since she was due to start filming Without Love (1945) with Spencer Tracy. After Jean Arthur nixed the idea too, the producers went after Warner Bros. contract starlet, Jane Wyman. Jack Warner was glad to loan Wyman to Paramount for what he called "that drunk film." The Lost Weekend was to be Wyman's first movie on which she received co-star billing above the title. Moreover, Wyman earned a great deal of recognition for her acting ability, after years of playing light romantic comedies.

Doris Dowling was cast as the tempting siren Gloria in The Lost Weekend. It marked the chorus girl's first movie role, and the beginning of her affair with Billy Wilder, who was on the verge of a divorce from his wife. However, Wilder later became infatuated by a brunette extra who was hired to play a coat check girl in the scene where Don Birnam gets thrown out of a bar for stealing money from a woman's purse. It proved to be a non-role for the extra, since only her arm can be seen giving a coat to Birnam, but no matter. The extra's name was Audrey Young, and she eventually married the smitten director. After so many other Hollywood marriages hit the rocks or the ashcan of history, Billy and Audrey Wilder are still married to this day.

When The Lost Weekend was given its first public showing at a sneak preview in Santa Barbara, California, the audience reaction to the intense film was not good. The audience laughed. Wilder recalled, "The people laughed from the beginning. They laughed when Birnam's brother found the bottle outside the window, they laughed when he emptied the whiskey into the sink." The theater lost viewers like a broken sieve. Preview cards were handed out, and the

opinions of the flick ranged from "disgusting" to "boring." Wilder even claimed that one patron left the theater proclaiming, "I've sworn off. Never again." "You'll never drink again?" he was asked. "No, I'll never see another picture again." Another preview card said that the movie was great, but that all the "stuff about drinking and alcoholism" should be omitted!

After the negative response to the controversial picture, some Paramount executives were ready to cut their losses, but studio president Barney Balaban said, "Once we make a picture, we don't just flush it down the toilet!" Balaban was right, there was still some room for major improvements in the picture, particularly in the music department. Composer Miklos Rozsa thought that the temporary music score, which was in the George Gershwin vein, was the chief reason for the unexpected reactions. Rozsa got the green light from Wilder and Brackett to bring to the soundtrack some experimentation with the eerie sounds of the electronic instrument known as the theremin.

While the fate of The Lost Weekend hung in the balance, the liquor industry made a move to have the film's negative destroyed. With gangster Frank Costello serving as their broker, the liquor industry made a secret offer of $5 million for Paramount to remove The Lost Weekend from their release slant.

In light of the questionable future of The Lost Weekend, Billy Wilder made a surprising decision: he joined the Army. The military's Psychological Warfare Division needed someone in Germany to oversee a program to expose Nazi supporters in the German movie and stage industry. Given Wilder's German film background and his command of the language, he proved to be a perfect fit. Wilder served with distinction until he learned that The Lost Weekend was experiencing a renewal of interest among Paramount's executives. To encourage their enthusiasm for the project, Wilder flew back from Germany after his discharge, having served in the Army during the spring and summer of 1945.

Once Paramount became a believer in The Lost Weekend, the director made the famous quip - "If To Have and Have Not (1944) established Lauren Bacall as The Look, then The Lost Weekend certainly should bring Mr. Milland renown as The Kidney."

Some temperance unions incorrectly accused The Lost Weekend of promoting or publicizing drinking. The Ohio temperance board objected to a line in the script attributed to the sadistic orderly, Bim. He says, "Prohibition-that is what started most of these guys off." Bim also makes a slam against "narrow-minded, small-town teetotalers." Paramount refused to remove the line, but Ohio won in the end. Paramount was also warned that the delicate sensibilities of the British might be offended by The Lost Weekend. The studio nixed any potential trouble by adding a subtitle for the British release, The Lost Weekend: Diary of a Dipsomaniac, and producing a special trailer alerting Britons of the film's harsh subject matter. The disclaimer read: "Ladies and gentlemen, as this is a most unusual subject for screen presentation, we have been requested to warn you of the grim and realistic sequences contained in this unique diary carrying such a powerful moral."

By Scott McGee

The Big Idea

by Scott McGee | March 02, 2007

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM