SYNOPSIS

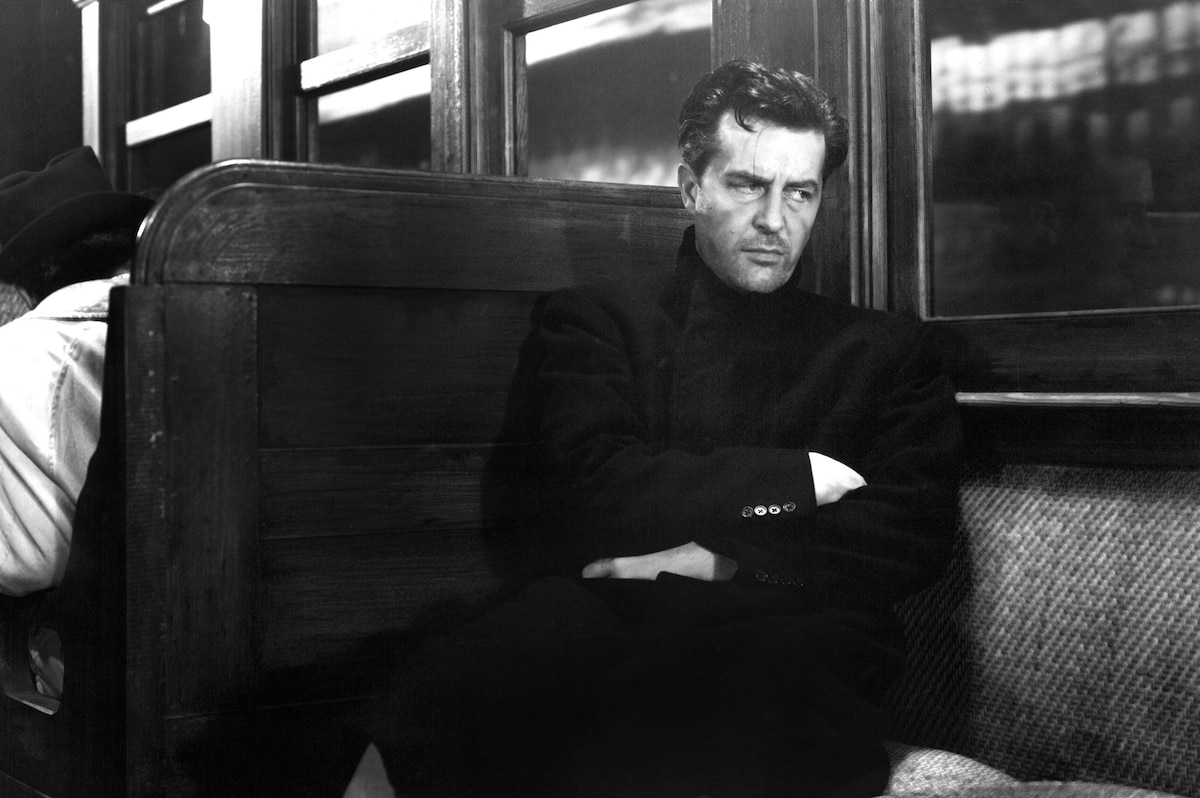

Don Birnam (Ray Milland) is a struggling writer. Everyday he bangs away at his typewriter, trying to compose something he can sell to meet the rent, and to keep his creativity alive. But instead of completing pages of manuscript, Don is only adept at finishing off bottles of liquor. Burdened with a severe case of writer's block, he turns to alcohol for inspiration and emotional support. Wick (Phillip Terry), Don's brother, tries to bring his sibling back from the abyss of alcoholic despair. Even the protestations of Don's girlfriend, Helen (Jane Wyman), are not enough to stop the writer's descent into a black hole from which he may never return.

Producer: Charles Brackett

Director: Billy Wilder

Screenplay: Charles Brackett, Billy Wilder, based on the novel by Charles R. Jackson

Cinematography: John F. Seitz

Film Editing: Doane Harrison

Art Direction: Hans Dreier, A. Earl Hedrick

Music: Miklos Rozsa

Principal Cast: Ray Milland (Don Birnam), Jane Wyman (Helen St. James), Phillip Terry (Wick Birnam), Howard Da Silva (Nat), Doris Dowling (Gloria), Frank Faylen ("Bim" Nolan), Mary Young (Mrs. Deveridge).

BW-101m. Closed Captioning.

Why THE LOST WEEKEND Is Essential

The mark of The Lost Weekend on American cinema was a lasting one, due in no small part to its controversial content and subject matter. But they say timing is everything, and when a movie that grapples with the subject of alcoholism shows up at the nation's theaters just as World War II is wrapping up, the cliche proves to be true. Americans fighting in Europe and the Pacific saw and experienced unprecedented inhumanity and violence. Thousands of

returning soldiers suffered nightmares, trouble in their relationships, and difficulty in adjusting to civilian life. The premise that a talented man, such as Don Birnam, could seek comfort and confirmation for his own shaky self-confidence in the bottom of a liquor bottle was not too far-fetched for returning G.I.s. Thousands of them sought hard drink to drown out the din of

combat and the loss of former comrades who did not return from the front. Many industry insiders were afraid that the relatively young director Billy Wilder (The Lost Weekend was his fourth directorial effort) and his movie would cross the line of proper subject matter for popular entertainment. Wilder and company did cross the line, only to prove that difficult or challenging content could be artfully and entertainingly created for a mass audience.

The issue of alcoholism affecting the lives of returning G.I.s can be found in director William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), particularly in Fredric March's character, a good man who is beginning to develop a drinking problem. Although Wyler's film doesn't sidestep the problems of alcohol dependency, it was The Lost Weekend that made the disease the central focus of the story and not a subplot, finally bringing the issue front stage and center for American moviegoers. The film was also the first to treat drinking seriously and not play it for laughs. Gone were the inebriated Nick and Nora Charles of The Thin Man movies. Gone

was the laughter inspired by W.C. Fields imbibing a snifter of liquor in his coat pocket. Any laughter emanating from viewers of The Lost Weekend was ironic at best.

Billy Wilder also brought his appreciation of German expressionism to a melodrama that accurately conveyed the lead character's state of mind. German expressionist cinema was a highly visual approach to the medium that allowed filmmakers to present disturbed, insane, or alienated characters through warped surroundings or distorted camera angles. Some classic examples include The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and M (1931). The film noir period in Hollywood also employed expressionist techniques to convey the menace of the city, while also showing the protagonist's point of view, such as detective Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell) in Murder, My Sweet (1944). Wilder was no stranger to noir, having directed one of the most important films in the genre, Double Indemnity (1944). But it was with The Lost Weekend that Wilder used German expressionism - not so much to show the corrupting influence of the city - but to show the psychological turmoil raging in Don Birnam's head.

By Scott McGee

The Lost Weekend - The Essentials

by Scott McGee | March 02, 2007

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM