Nothing But a Man ('64) was simply ahead of its time. This story of a young black man facing prejudice in the Deep South was born out of the Civil Rights era but was too brutally honest and uncompromising to be fully appreciated by contemporary audiences. Film historian Donald Bogle noted that the film "is so far removed from stereotypes and caricatures... it's authentic." Ivan Dixon, the film's star, plays Duff - a black man who refuses to play by the rules, choosing a career as a traveling railroad worker rather than a more traditional job. When Duff falls for schoolteacher Josie (Abbey Lincoln), he attempts to settle into small town life, but this comes at a price as he faces a white community who yields unrelenting power over the black one.

The idea to make Nothing But a Man came from director Michael Roemer's experience growing up in Germany during WWII. His Jewish family was persecuted by the Nazis and 11-year-old Roemer escaped by way of a Kindertransport that took him to England. He eventually moved to the United States, studied at Harvard and became a documentarian working for the news department at NBC. Marked by his personal experience with prejudice, Roemer became interested in the effects of racism on the black community. He teamed up with fellow NBC employee Robert M. Young to develop an idea for a feature film. In an interview with The New York Times, Roemer said, "we thought that the most powerful, useful political statement would be a human one."

With the help of the NAACP, Roemer and Young went on a three-month research trip to the South to gather material for their script. Not only did they see firsthand the effects of discrimination and segregation, they also encountered antisemitism. They returned to New York City and wrote the script in six weeks. Young's vision was to capture the social and economic effects of racism, and for Roemer, it was to paint the portrait of a marriage born out of turbulent times. They both served as producers on the project along with Robert Rubin, another NBC employee, who also worked on the sound.

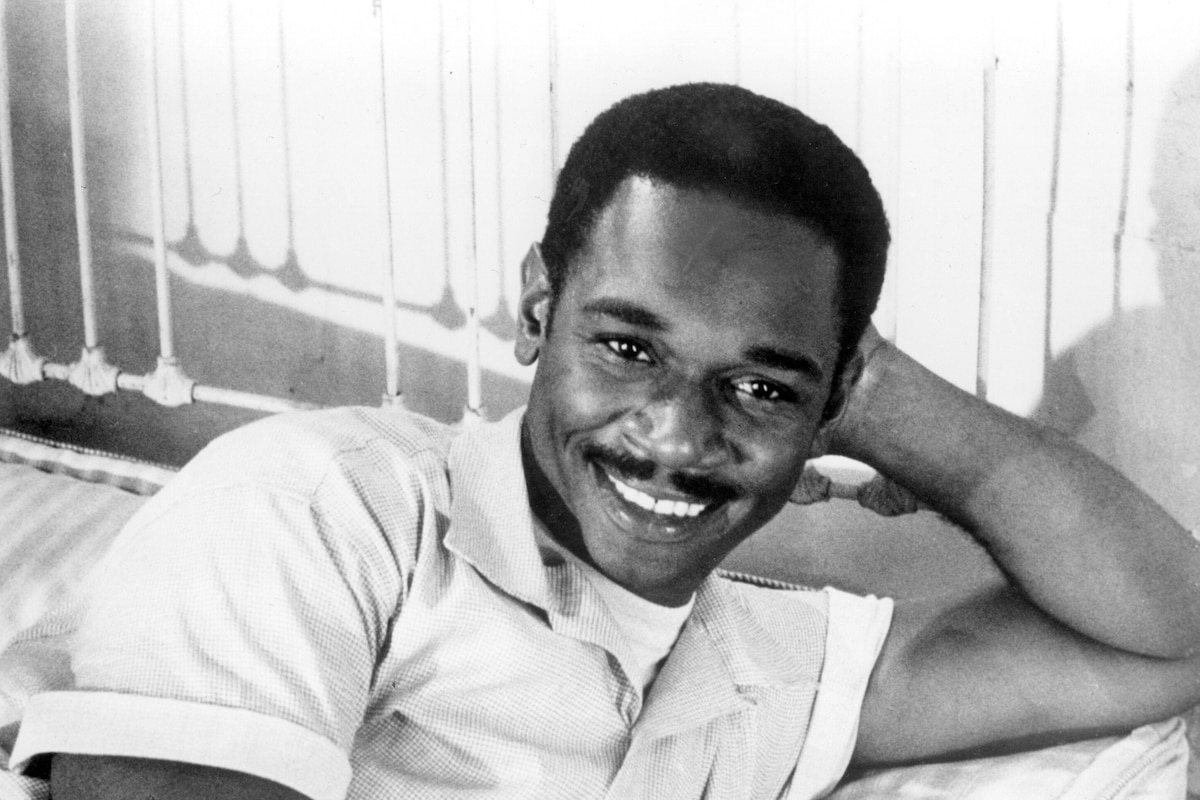

Black actor-playwright Charles Gordone, the cofounder of the Committee for the Employment of Negro Performers, was hired to cast the film. According to the AFI, casting calls for black actors appeared in Variety and those selected were invited to audition at the DuArt Film Laboratories in New York City. James Earl Jones tried out for the part of Duff but ultimately didn't agree with some of the early scenes in the script. Sidney Poitier turned down the role of Duff which went to his good friend Dixon. Dixon and Poitier had worked together on films such as Something of Value (1957), The Defiant Ones (1958) (Dixon was Poitier's stunt double), Porgy and Bess (1959), A Raisin in the Sun (1961) and A Patch of Blue (1965). The role of Duff was an opportunity for Dixon to play a leading part with substance and to step out of the shadow of his more famous friend. He'd never get a role quite like that again and would later look back on it as the highlight of his acting career. Duff was a unique part and as Donald Bogle noted, "he is sensitive, he is intelligent, he is emotional and he is sexual without being hyper-sexual as we later see in the movies of the Blaxploitation era."

Opposite Dixon was Abbey Lincoln as Josie Dawson. Lincoln was a jazz singer and Civil Rights activist. After Nothing But a Man she starred with Poitier in For Love of Ivy (1968) as the title character. Former nurse and club bouncer, Julius Harris, who auditioned on a dare, was cast as Will Anderson, Duff's father. Stage actress Gloria Foster, who later became known for playing The Oracle in The Matrix films, delivers a powerful performance as Will's long-suffering girlfriend Lee. Other actors making their film debut include Tom Ligon, William Jordan, Helene Arrindell, Walter Wilson, Gertrude Jeannette, Leonard Parker, Martin Priest and Charles McRea. Up-and-coming actor Yaphet Kotto got his first on screen credit for his role as Jocko.

Principal photography began in March 1963 and wrapped up by the end of October. Most of the filming was done in Atlantic City and Cape May, NJ, with other scenes shot in Mississippi, Georgia and Alabama. The production cost between $230,000-$300,000 and used live rather than dubbed sound. Every member of the cast and crew was paid $100 a week. Roemer and Young were particularly influenced by documentary filmmaking and by the work of Vittorio De Sica and Roberto Rossellini. Nothing But a Man interweaves documentary footage with acting sequences giving the film a notable sense of realism. The soundtrack features music by Stevie Wonder, The Miracles, The Marvelettes and others. Roemer had met with former Harvard classmate George Schiffer who had suggested that Roemer reach out to Motown Records. Roemer paid Motown owner Berry Gordy $5,000 for the music.

Nothing But a Man was produced by DuArt Film and Video in collaboration with Roemer and Young's Nothing But a Man Company and distributed by Cinema V, a company who specialized in race films. It premiered on September 19th, 1964 in New York City and had a limited run in select cities including a one-week run at the Vagabond Theatre in Los Angeles in order to qualify for Academy Awards consideration. A screening at the Venice Film Festival met with great critical acclaim and it received a San Giorgio prize, the Award of the City of Venice (Roemer) and the New Cinema Award for Best Actress (Lincoln). Back at home Nothing But a Man received an enthusiastic response at the New York Film Festival and multiple bids for wider distribution. Other accolades included an endorsement from the Nation of Islam newspaper Muhammad Speaks, recognition for Ivan Dixon's performance by a Senegalese film festival, and a Star Crystal award from the National Council of Churches Broadcasting and Film Commission. However, Nothing But a Man failed to garner the public's attention, no thanks to Cinema V's marketing which advertised the film as sexploitation, and the film quickly fell into obscurity.

Nothing But a Man got a new lease on life when a restored print was released in 1993. The Washington Post called the film, "one of the most sensitive films about black life ever made in this country." In his review, Robert Ebert wrote "the movie is even better than I remembered it; the basic drama remains strong, but what's also surprising is how well the more subtle moments hold up, and how gifted the actors are." Nothing But a Man got a second chance at life with critics and audiences praising the portrayal of black characters, the moving performances and its realism. The film was selected by the Library of Congress for inclusion in its National Film Registry. It was released on DVD in 2004.

By Raquel Stecher

Nothing But a Man

by Raquel Stecher | January 06, 2020

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM