Ian Fleming wrote Casino Royale, his first Bond novel, in 1952. At the time of his death in 1964 at the age of 56, he had been working on what he had declared would be his very last Bond novel: The Man with the Golden Gun. The manuscript was mostly finished, but it was a first draft missing the usual layers of added detail and refinement given to the previous Bond novels. Published posthumously in 1965, it garnered some modest reviews but was still a best seller and part of a body of work that had made Fleming one of the most acclaimed British writers of his time with over 100 million copies sold worldwide.

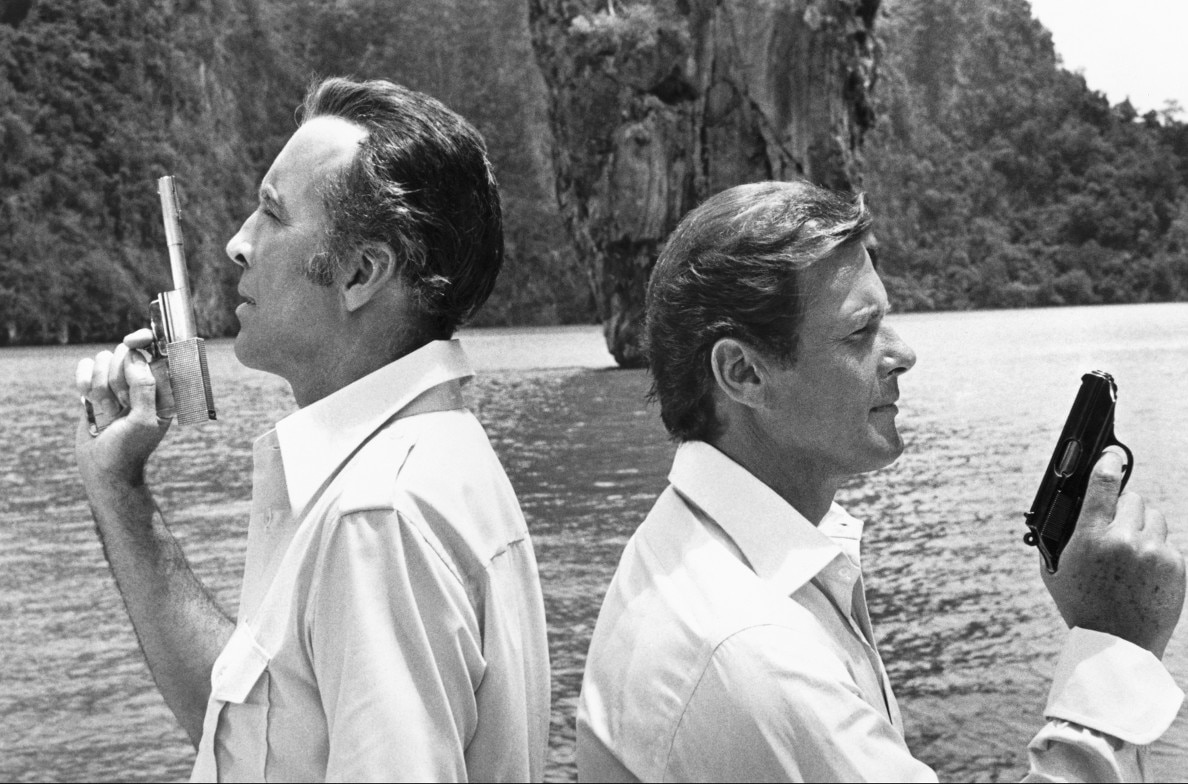

Guy Hamiltons loose cinematic adaptation of Flemings book came out in 1974 working on a script written by Bond veterans Richard Maibaum and Tom Mankiewicz. Roger Moore was brought on board for what would be his second stint (out of seven) as James Bond. The Man with the Golden Gun was Hamiltons fourth and final Bond movie. It was also the last Bond film to be co-produced by Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman before their relationship deteriorated to the point that Saltzman sold off his half of the stake in the parent company of Eon Productions. Performers who return to play familiar roles include Bernard Lee (as M), Lois Maxwell (as Miss Moneypenny) and Desmond Llewelyn (as Q). New to the beat as the titular villain: Flemings step-cousin, Christopher Lee (the only Bond villain to have a familial relation to the author). Accompanying him and also new to the Bond world: Hervé Villechaize as Nick Nack. It was a break-out role for Villechaize, one that rescued him from living out of his car in L.A., and one that put him on an island years before being cast by ABC to work alongside Ricardo Montalbán as the plane-welcoming Tattoo.

The Man with the Golden Gun begins on an exotic island hideout that was filmed in the Phang Nga province of Thailand. Our villain, Francisco Scaramanga, emerges from his ocean swim and this gives the camera an opportunity to zoom in on his third nipple something Mike Myers would later lampoon in Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002). Nick Nack, in snazzy attire, serves them champagne and a short while later welcomes a hired gangster into a secret chamber tricked out with dummies and mirrors. The gangster thinks hes getting paid to do a hit job with his signature golden gun but is duped, which sets off a chain of events involving Her Majestys Secret Service and 007. Mixed into the intrigue is a solex agitator that could be used to solve the energy crises, if left in the right hands, or that could be put to nefarious means if Scaramanga has his way.

Bringing Bond in to solve the energy crises seems timely today but was even more so back in the early 70s when Britain had not yet tapped into North Sea oil and gas. Of course, the main joys to be had are in seeing exciting action scenes unfold across a string of exotic locations, and for The Man with the Golden Gun these include Hong Kong, Beirut and Bangkok. One particularly inspired highlight is the use of a derelict cruise liner, the RMS Queen Elizabeth, as a top-secret base in Hong Kong harbor, one that uses a canted set that echoes the funhouse theme evoked by the first scene and also gives a nod to German Expressionism.

Other recurring tropes are exotic cars (including a brown and gold 1974 AMC Matador X Coupé, which becomes a carplane) and dangerous car stunts (including a cork-screwing car jump so unique the producers paid to patent the stunt to keep anyone from replicating it before the films release). If there is one glaring misstep in the production, one admitted to by both the director and composer John Barry, it involves the latter stunt being accompanied by a goofy slide-whistle sound that saps the incredibly dangerous moment of its full potential. That fleeting error aside, watching The Man with the Golden Gun contains within it the pleasure of seeing long-time chums (they first met in 1948) Sir Christopher Lee (knighted in 2009) and Sir Roger Moore (knighted in 2003) having their fun.

Although The Man with the Golden Gun was profitable, the box office was considered disappointing by contrast to previous Bond titles. Some speculation suggested that Roger Moores star persona, being linked as it was to his previous television career as Simon Templar in The Saint and the aristocratic playboy Lord Brett Sinclair in The Persuaders!, while a distinctly comforting national stereotype of the English gentleman hero in the UK, didnt connect as well with American audiences who preferred Sean Connerys more muscular and Scottish approach. That would change with the spectacular success later obtained with Lewis Gilberts Moonraker (1979), which was able to ride the resurgent interest in all things sci-fi thanks to Star Wars (1977) along with a plot involving the U.S. space shuttle two years before its first flight.

By Pablo Kjolseth

The Man with the Golden Gun

by Pablo Kjolseth | August 22, 2019

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM