"Only the British could be so funny," declared the Motion Picture Herald in its review of The Mouse That Roared (1959). That statement gave Jack Arnold and Walter Shenson a laugh, for they were the very American director and producer of said motion picture. The Mouse That Roared was made in England, however, and with a British cast. It has since become a comedy classic.

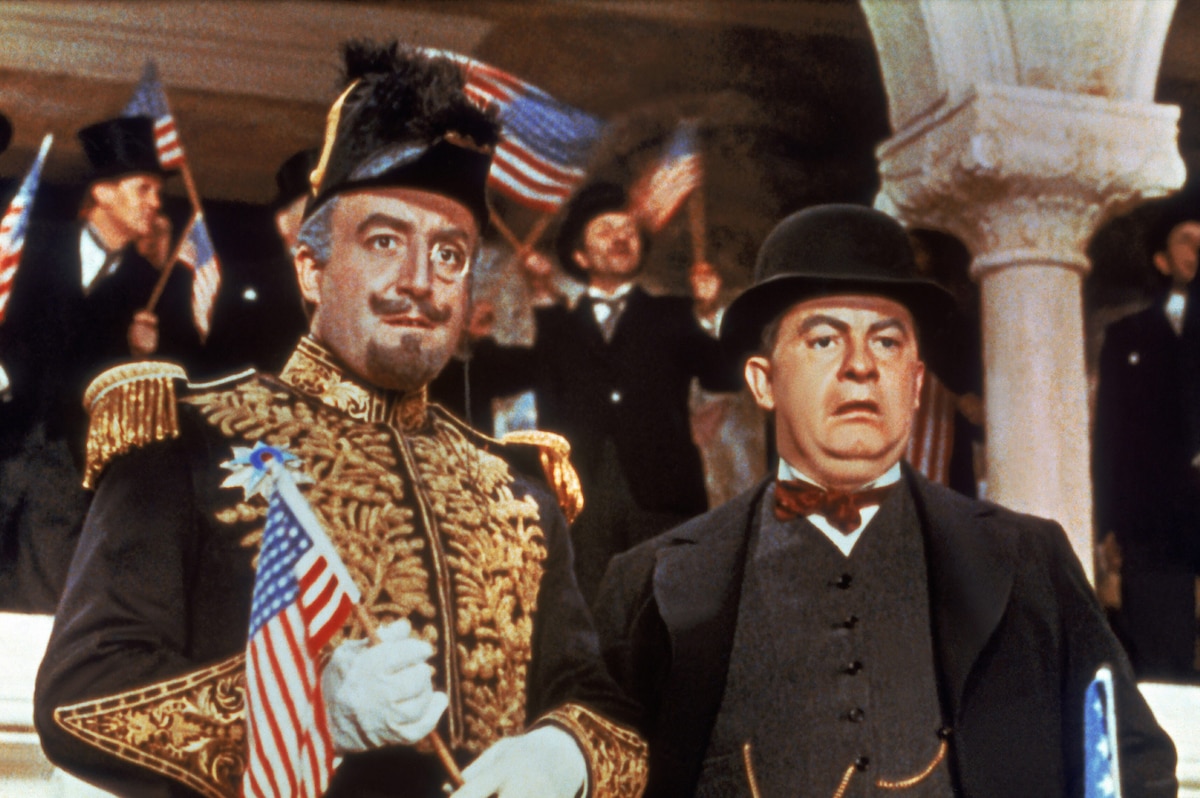

The story imagines a fictitious country called Grand Fenwick going bankrupt because its one export, a wine, has been duplicated by a California company which sells it cheaply. Prime Minister Count Mountjoy (Peter Sellers) tells Grand Duchess Gloriana XII (Peter Sellers, again) that tiny Grand Fenwick must declare war on the United States, lose immediately, and then reap the foreign aid that the U.S. always bestows on countries it defeats. In a tour de force, Sellers plays a third role of Tully Bascombe, the officer who leads Fenwick's 20-man army into New York City. Their plan of defeat goes awry when Bascombe wins the war by capturing the inventor of the United States' "Q-Bomb," which has the capacity of 100 hydrogen bombs. International complications ensue as other countries now want the bomb for themselves.

The screenplay was based on a novel by Leonard Wibberley first serialized in the Saturday Evening Post as The Day New York Was Invaded. Wibberley came upon his story idea while writing an editorial for the Los Angeles Times about the fact that Japan was receiving a windfall of aid from the U.S. after losing WWII. Perhaps, he hypothesized, it was better for a country to lose a war with America than to win. Wibberley's novel found its way to Walter Shenson, who was working as a publicist for Columbia Pictures in England at the time. Shenson loved it, personally bought the screen rights, and pursued producing it. Eventually, Carl Foreman agreed to finance it through his High Road Productions because he saw it as a small, inconsequential film to which he could charge office expenses for The Guns of Navarone (1961), which was entering pre-production. (Foreman, another American, was the blacklisted screenwriter of High Noon, 1952, and had re-established himself in London.)

Columbia Pictures agreed to distribute the picture, and Foreman and Shenson hired Jack Arnold to direct. Though best-known for his sci-fi films like Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), Arnold would later call The Mouse That Roared his favorite film. It's filled with outrageous jokes, starting right off the bat with a visual gag involving the Columbia Pictures statue of liberty logo. She hikes up her skirt and runs off the podium, frightened by a mouse. "I didn't ask them for permission, I just shot it," Arnold later said. "The audience laughed so hard, without even the story beginning, that we were home free. It set the tone for the whole film."

Beneath the movie's comedy is a serious statement on the absurdity of war and the danger of nuclear weaponry. Arnold recalled: "It was a way of making a social comment I felt was important. The most effective way to make a social comment is by satire and comedy... Luckily there was no pressure on me from anybody, except to make a good film from Walter Shenson who was the line producer and who was in complete agreement with what I wanted to do... The producers left me alone because (1) they didn't think it meant anything, and (2) they were just writing it off for expenses anyway."

Columbia did insist on casting Jean Seberg, however. She had just done two pictures for Otto Preminger and was a known "name," unlike Peter Sellers at this time. Arnold described Sellers as "a marvelous improvisational actor, brilliant if you got him on the first take. The second take would be good, but after the third take he could really be awful. If he had to repeat the same words too many times they became meaningless."

The director improvised as well. When he was in Southampton shooting a tugboat scene, "I saw the Queen Elizabeth coming in to [port]. I was on the cameraboat and over the radio I told the captain of the tug to get as close to the Queen Elizabeth as she could get, and tell all the boys to shoot arrows at her. I had three cameras on the boat itself and we got a sensational little sequence." Later on, a replica of the Queen Elizabeth's bridge was constructed on a sound stage and a scene was written for the ship's captain and first mate.

Not everyone was so gung ho during production. Arnold recalled: "Walter and I laughed a lot at the dailies in London, but Carl Foreman and Whiteman, head of Columbia in Europe, weren't laughing. They thought it was a disaster. It was so discouraging I quit going to dailies and asked Walter to watch them for me... When we previewed the finished film, they laughed so hard...that Foreman immediately had all the prints recalled and changed 'High Road Presents' to 'Carl Foreman Presents.'" The Mouse That Roared slowly became a word-of-mouth sensation. It played in small arthouses for a full year before going into general release - something which would be unheard of in today's quick-to-DVD marketing schedules.

A sequel entitled The Mouse on the Moon (1963), directed by Richard Lester, did not star Sellers and is forgotten today. Walter Shenson again produced it, then went on to produce A Hard Day's Night (1964) and Help! (1965) for The Beatles.

Producer: Jon Penington, Walter Shenson

Director: Jack Arnold

Screenplay: Roger MacDougall, Stanley Mann, Leonard Wibberley (novel)

Cinematography: John Wilcox

Film Editing: Raymond Poulton

Art Direction: Geoffrey Drake

Music: Edwin Astley

Cast: Peter Sellers (Grand Duchess Gloriana/Prime Minister Mountjoy/Tully Bascombe), Jean Seberg (Helen Kokintz), William Hartnell (Will Buckley), David Kossoff (Professor Alfred Kokintz), Leo McKern (Benter), MacDonald Parke (General Snippet).

C-83m. Letterboxed.

by Jeremy Arnold

The Mouse That Roared

by Jeremy Arnold | August 14, 2006

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM