A "first-person shooter" film noir that bathes its loathsomely cynical

misanthropes in sunny studio lighting, backs them up with eerie choral

singing instead of an orchestral soundtrack, and pretends (for a while)

to be a Christmas picture,Lady in the Lake is one of the oddest

things ever to issue forth from the studio vaults. That this avant-garde

work of cinematic experimentation was bought and paid for by MGM of all

places, the toniest and most traditionalist of the major studios, only

makes this bizarre concoction seem even stranger.

By 1947, Raymond Chandler was big business. His hard-boiled pulp

novels (many of them about the Don Quixote-like private eye Philip

Marlowe) were wildly popular, as were their increasingly gritty film

versions. Chandler himself took up residence in Hollywood, adapting his

own books into screenplays (The Big SleepDouble Indemnity), and penning original screenplays (The

Blue Dahlia). The character of Philip Marlowe had been essayed by

Dick Powell and Humphrey Bogart, as well as (if you're not too precise

about the name "Philip Marlowe" actually being used) Lloyd Nolan and

George Sanders. So, when Robert Montgomery proposed to MGM that he get

to star in-and direct-a version of Lady in the Lake, contemporary

audiences could be forgiven for expecting a little more of the same old

same old: another dimly-lit and archly-worded journey into Raymond

Chandler's peculiarly overcomplicated brand of noir.

But is Raymond Chandler's pulp fiction was becoming a genre unto

itself, with its own calcified rules and conventions, Robert Montgomery

was the proverbial square peg in the round hole. In 1947, Chandler was

disillusioned and frustrated with Hollywood, and all but left town;

Montgomery was just finding his calling, and looking to expand his

horizons. One man's grumpy disillusionment is another man's trippy

dream, so to speak.

Robert Montgomery had first come to Hollywood with the desire to

be a screenwriter. "Yeah, I'm a top-billed movie star, but I really want

is to write!" With his bland, somewhat doughy, good-looks and a vocal

delivery that sounded like Cary Grant minus his distinctive accent,

Montgomery racked up roles in over 50 films prior to 1945, settling

happily into a rut as one of Hollywood's less-interesting performers.

1945, though, was when Fate struck a surprising blow: on the set of

They Were Expendable, John Ford got sick. Montgomery filled in

for him, secretly. He enjoyed the taste, and wanted more.

In the main, actors-turned-directors generally make movies that

are actors' showcases, not ones that push the limits of the cinematic

form. Montgomery the iconoclast chose that later path. For years, film

theorists had puzzled over the role of the camera lens-did it have a

narrative function, and if so, what? Does the audience identify more

with the characters onscreen, or with the unseen perspective from which

those characters are witnessed? The idea of using the camera's viewpoint

as a character had kicked around Hollywood before, but to actually go and

do it, in a prestigious studio vehicle, took a degree of daring no one

had yet mustered. Full of daring bravura, Montgomery cast the camera as

Philip Marlowe; he would provide little more than the voice.

MGM's publicity boasts "YOU and Robert Montgomery solve a murder

mystery together!" It is doubtful anyone really thought about this

technique as a sort of virtual reality project, with the viewer suckered

into "being" the main character. The plot is too tangled to be deduced

by any viewer-who is not watching the events "as" Philip Marlowe so much

as staring passively through Marlowe's eyes. This is a crucial

distinction, because the consequence of the subjective camera is a

colder, more distancing film than one shot more conventionally.

Marlowe's attention, for that matter, wanders. He may stare at

another character for what seems like an eternity... or he may leer at some

passing woman instead. If he gets bonked on the head (which happens a

lot) the screen goes black; if he's alone, several minutes may pass while

he stares blankly at an empty corner of a room. We see what he sees: but

he may not be looking at anything particularly interesting at the time.

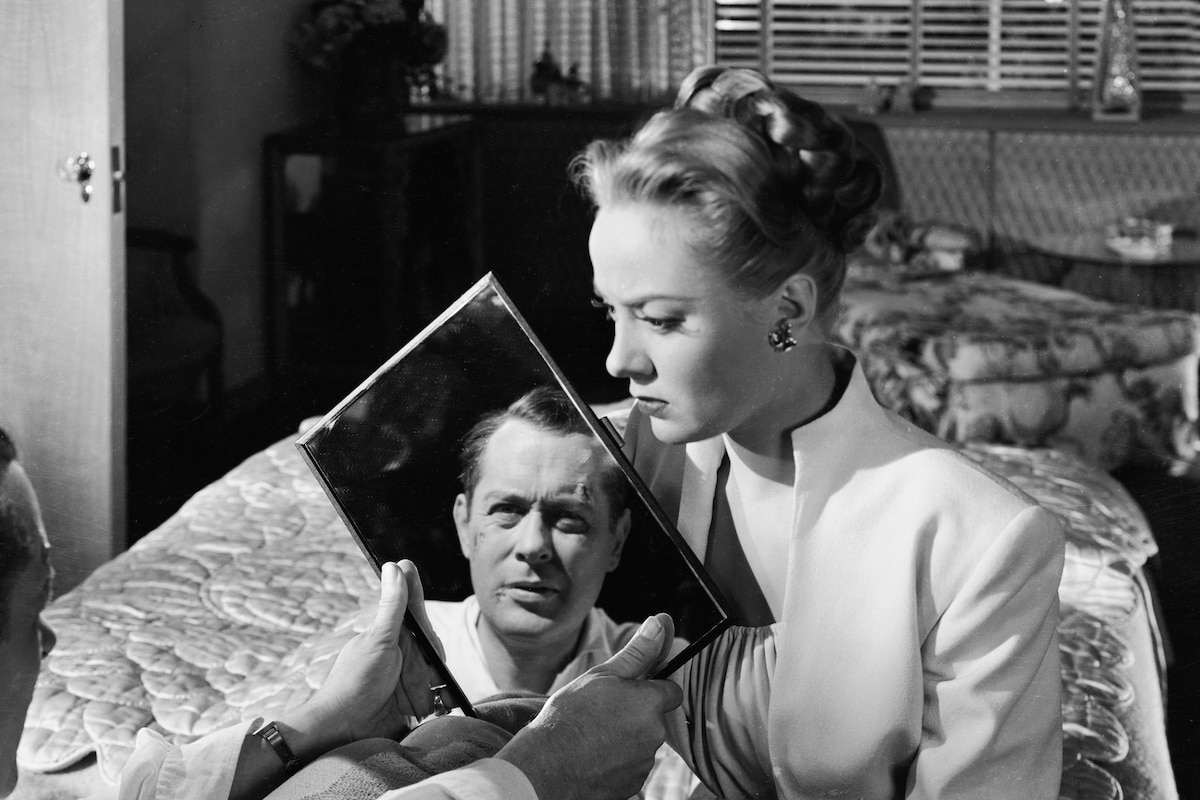

For a wraparound framing sequence, Montgomery appears onscreen as

Marlowe in his office, talking directly to the audience. It is awkward,

to say the least-we in the audience are simply not accustomed to being

addressed like that. Nor are professional actors accustomed to doing

it-Lloyd Nolan in particular found the experience discomfiting. Even in

today's post-Roger Rabbit green-screened CGI-ville, not all actors

come equipped to properly emote to ciphers and phantoms.

The experiment placed huge and unprecedented demands on the cast.

Marlowe is offscreen for almost the entire movie, save for when he

admires himself in a mirror or narrates directly at us. We cannot

see his reactions to anything. His body language is silenced, his facial

expressions invisible. With Marlowe reduced to a voice-over, all the

burden of performing onscreen shifts to the other actors, who have to

carry the picture on behalf of its all-but-absent star. Audrey Totter is

more than up to the challenge, and brings enough facial gymnastics for

two. Her eyes roll, her nostrils flare, her lips pout, she glowers with

a smoldering power so intense it's a miracle the celluloid didn't catch

fire in the camera.

Good thing, too, since cinematographer Paul Vogel and his team

had their hands full. Maintaining the premise that the camera sees what

Marlowe sees severely limits the cinematic options, and reduces the art

of editing to a game of cheats: cuts are hidden when possible, avoided

altogether when not. If it takes a badly beaten man a few minutes to

crawl on his hands and knees across a highway to a phonebooth, rest

assured it will take the exact same number of minutes of screen time to

watch this happen (and from his point of view, natch). While the result

is more gimmicky than dramatic overall, it results in a handful of

standout sequences, the best of which is a genuinely suspenseful and

nerve-jangling car chase-and anytime someone manages to make a car chase

seem fresh, it is a cause for celebration.

One wonders what producer George Haight thought of all this. He

was not of a noir sensibility, and this was a marked deviation for him.

Screenwriter Steve Fisher was a veteran of pulp thrillers, and punched up

Chandler's story with a canny eye for what would make it a better movie.

Although Montgomery's moon-eyed American-boy appearance seems at odds

with the hard-bitten Marlowe character he portrays, at least the

subjective camera keeps that minor quibble safely in the margins. From

his words, Marlowe is a "dumb, brave, cheap" dick caught up in a stew of

crooked cops and man-eating dames; drowned women and naked,

bullet-riddled pretty men; false identities and self-referential mystery

fiction; love triangles (or hexagons) and double-crosses that uncross

themselves-all ending in a trail of rice. It is by no means a typical or

representative film noir, but that is its enduring strength.

Warner Brothers' disc comes with a snappy and informative

commentary by film noir historians James Ursini and Alain Silver, as well

as an original theatrical trailer. It is packaged exclusively in the

multidisc Film Noir Classics Collection Volume 3.

For more information about Lady in the Lake, visit Warner Video. To order Lady in the

Lake (it is part of the Film Noir Classic Collection, Vol. 2), go to

TCM Shopping.

by David Kalat

Lady in the Lake - Robert Montgomery as Detective Philip Marlowe in LADY IN THE LAKE on DVD

by David Kalat | September 25, 2006

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM