Woodstock (1969) is both an epic concert film and a documentary snapshot of a social culture. The Woodstock Music & Art Festival, promoted as "3 days of peace and music," was intended to take place at Woodstock, New York in the summer of 1969 and the name stuck even after the city turned them away. With time running out, it ended up in Bethel, where farmer Max Yasgur leased his 600-acre farm to the festival organizers. The rolling hills of his alfalfa fields made for a natural amphitheater and the nearby lake made a lovely backdrop (and a hub for skinny dipping) during the three-day concert.

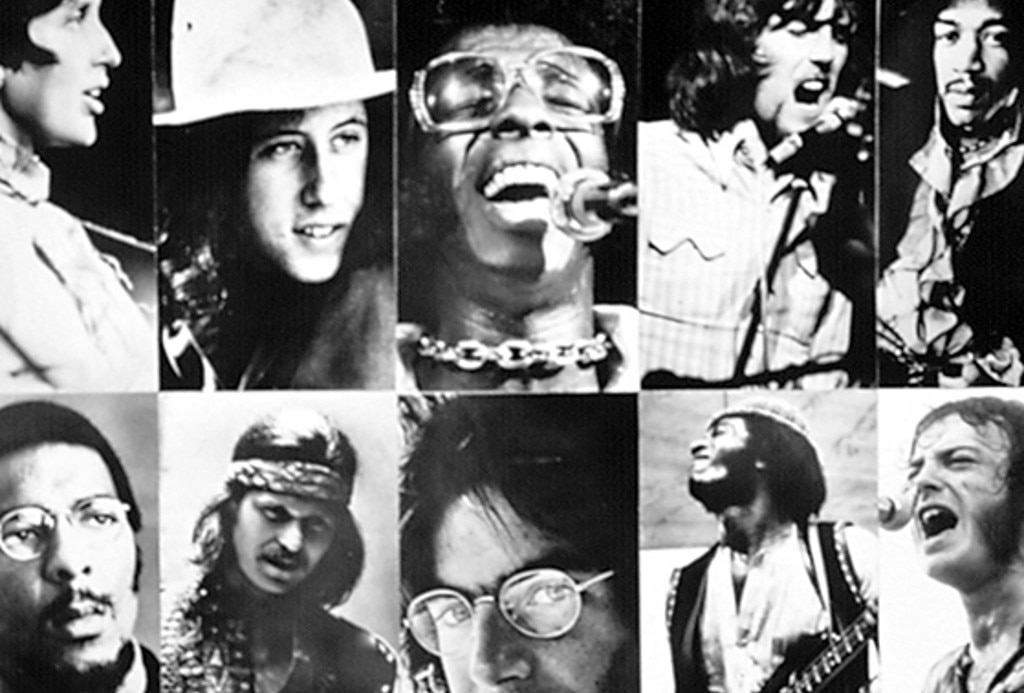

The organizers had planned for an audience of 200,000, but attendance swamped all expectations. As the staff rushed to prepare the site on short notice, roads became choked as people flooded in two days before the opening act was scheduled to play. Performers were flown in by helicopter to get them to the stage. Overwhelmed by the crowds, the festival simply opened the gates and let the stream of arrivals in for free. It kicked off on the afternoon of Friday, August 15th with a set by Richie Havens and ended early Monday morning on a legendary performance by Jimi Hendrix. By the time it was over, 32 acts had performed before an audience of 400,000. People famously pulled together to feed the crowds in makeshift outdoor kitchens ("What we have in mind is breakfast in bed for four hundred thousand") and for all the chaos, the event came off without violence or disruptive conflict. More than a concert, Woodstock became a symbol of an era and even lent its name to the times: "The Woodstock Generation."

Artie Kornfeld and Michael Lang, the festival entrepreneurs and producers, wanted to document the event. When Hollywood studios turned them down they approached Michael Wadleigh, a New York-based independent filmmaker. With very little money and no guarantee that they could secure the music rights, Wadleigh and producers Bob Maurice and Dale Bell threw themselves into the challenge with mere weeks to put it all together. They put the word out for camera operators and drafted students and alumni from the NYU film program as their crew. They figured they would need 365,000 feet of raw film stock for five cameras shooting practically around the clock. Despite promises from their film supplier, only a fraction of the necessary film stock was available by the time the concert began so they flew it in on the same helicopters that brought in the performers through the course of the festival.

Wadleigh was one of the camera operators on the five camera teams as well as the director. He attempted to use radio headsets to communicate with the other teams but interference, feedback, and breakdowns rendered that useless. Martin Scorsese, who had just graduated from NYU, was one of Wadleigh's assistants and would run messages to the other crews when voice or hand signals were ineffective. Though the performers supplied set lists to the crew, they rarely followed them. Wadleigh wanted to represent every act in the festival but couldn't record every song, so they simply began shooting at the start of every song and decided within the first 30 seconds whether to continue or cut it off. "Every single song was put in for its lyrical value, not just its musical value. We didn't select songs that were hits. We tried to use the lyrics like a poet would to tell a story." The crew worked around the clock for three days on little sleep and little food.

The production was shot entirely on 16mm film using the Éclair NPR, a lightweight, handheld camera designed for the operator to reload film quickly and to switch lenses on the fly. It enabled a greater flexibility to switch from the familiar long lenses used to shoot from a distance to wide-angle lenses, which they used when they mounted the stage during performances. Explains Wadleigh: "You could get right very, very close to the performers and it gave you a tremendous sense of depth and being there with the performers." He also sent teams wandering through the crowds to interview concertgoers and document the community that arose from the festival. Wadleigh was determined to make Woodstock about the entire event, not just the music but the crowds, the experience, and the political and social culture that gave birth to it.

When shooting was over, Wadleigh and his team crossed the continent to Los Angeles where they spent months sorting through the footage. Sound was recorded separately and teams spent months simply matching and synchronizing soundtracks. To deal with the overwhelming amount of footage, Wadleigh used the KEM editing machine from Germany, which enabled the editors to view three strips of film at a time. The process inspired the editing team, which was headed by Thelma Schoonmaker and included Scorsese, to use split screens to put more of the footage on screen. It was Scorsese's idea to print the lyrics to Country Joe McDonald's "Feel-Like-I'm-Fixing-to-Die-Rag" with a bouncing ball, which matched the whimsy of the anti-war song and turned the performance into an audience sing-along. And though the film was shot on 16mm, Wadleigh arranged for a 70mm release to make use of the superior sound.

Warner Bros. stepped in to finance and distribute the film, thanks to the efforts of Fred Weintraub, then a new, young executive at the studio. When the first rough cut ran over six hours, the filmmakers knew they were in for a conflict with a studio that expected a documentary at a conventional length. They packed the Warner screening (now cut down to about three and a half hours) with students from UCLA and USC to give the executives a sense of the youth response. It did the trick and the film was released to theaters in a cut running just over three hours.

Woodstock was a big hit for Warner Bros., scoring with young audiences and critics alike. It won the Academy Award for Best Documentary and was nominated in Sound and Film Editing categories. In 1994, Wadleigh created an extended director's cut, which ran 40 minutes longer, and in 1996 it was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress for the National Film Registry.

Sources:

Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Peter Biskind. Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Woodstock: An Inside Look at the Movie That Shook up the World and Defined a Generation, edited by Dale Bell. Michael Wiese Productions, 1999.

Defining Moments: Woodstock, Kevin Hillstrom and Laurie Collier Hillstrom. Omnigraphics, 2013.

Martin Scorsese: A Journey, Mary Pat Kelly. Thunder's Mouth Press, 1991.

"Woodstock: From Festival to Feature," 1K Studios. Woodstock: The Director's Cut Blu-ray, Warner Home Video, 2009.

By Sean Axmaker

Woodstock

by Sean Axmaker | October 17, 2016

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM