Cinematic provocateur Marco Ferreri created a dividing line of sorts in his career when he launched into the unforgettable, experimental Dillinger Is Dead as the turbulent 1960s came to a close. Up to this point he had been directing feature films for a decade, seasoning his eccentric tales like The Ape Woman (1964) and The Harem (1967) with just enough hints of perversity and rakish humor to get the attention of critics and put his name on the map.

However, it was with this film that Ferreri found perhaps his greatest leading man, one who would go on to symbolize the frustrations and stunted emotional development of the modern-day male as perfectly as possible: Michel Piccoli, who would return to the land of Ferreri in The Audience (1972), the underrated Liza (1972), Don't Touch the White Woman (1974), The Last Woman (1976), and the most notorious film either man ever made, La Grande Bouffe (1973). What makes Dillinger so special is the opportunity to shine the spotlight entirely on Piccoli, a fearless but often low-key French actor whose first major role came in 1954's French Cancan for director Jean Renoir. Over the course of his career, Piccoli was already in demand by some of the world's most respected names like Jean-Luc Godard (with Contempt in 1963), Luis Buñuel (Diary of a Chambermaid in 1964, Belle de Jour in 1967, and The Milky Way in 1969), Alfred Hitchcock (Topaz in 1969), and Jacques Demy (The Young Girls of Rochefort in 1967), not to mention an amusing turn in Mario Bava's Danger: Diabolik (1968).

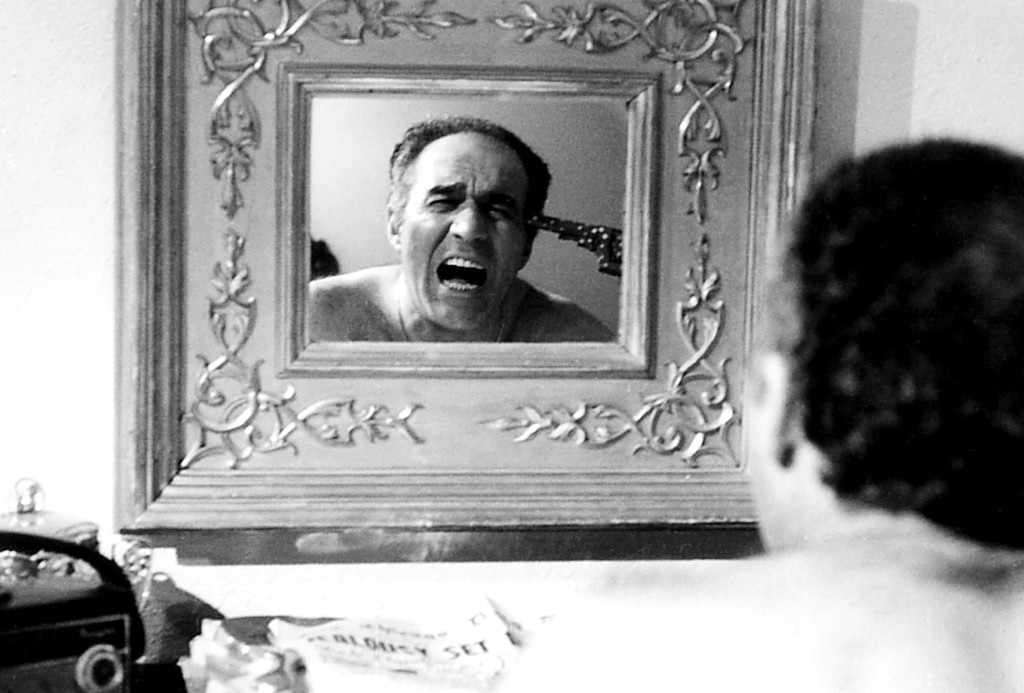

Unseen in American theaters until 2009 (a fate still better than the majority of Ferreri's films), Dillinger Is Dead arrived as Europe was still in the throes of massive political and social upheaval, with France and Italy in particular afflicted with a string of riots, angry protests, and extremist movements that caused many to question whether the traditional family unit would disintegrate entirely. A designer of gas masks, identified in the official credits as Glauco (Piccoli), becomes a symbol of this unease as he comes home for a fateful evening to find his wife (Anita Pallenberg, in the middle of a hot streak between Barbarella and Performance) convalescing from a severe headache and unable to provide him with more than a tepid plate of leftovers for dinner. As he prepares his own savory meal for the evening, he discovers a pistol wrapped in a newspaper dating from the demise of famed outlaw John Dillinger. Already harboring a rebellious streak that causes him to make moves on the family maid (French cinema staple Annie Girardot) and fantasize about the iconic Dillinger, he closes the evening with a dramatic and violent gesture that puts him on the path to an extreme life change.

"I am in all the film, continuously," Piccoli noted in an interview with Cahiers du Cinéma's Cyril Béghin in 2005. "It's a question of the desperation of man who has made it' who no longer knows where to go. It caused a scandal, so much ferocity on the condition of the 'parvenus,' as we said at the time. Too violent, too dangerous. Ferreri didn't direct me for a second during the shoot; he would simply give spatial indications. It was up to me to play this solitary person, this solitude, this eternal child or this childlike rebirth of "mature" man, between despair, suicide, simple insomnia, dream." Fortunately the film didn't prove to be too much for French viewers, who responded positively when it was entered in the 1969 Cannes Film Festival and received enthusiastic notices upon its release throughout the country. Welcomed with open arms, Ferreri went on to live and produce films in Paris for much of his remaining life. Whether the rest of the world has understood and appreciated what he produced from this film onward remains to be seen.

By Nathaniel Thompson

Dillinger is Dead

by Nathaniel Thompson | May 23, 2016

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM