After making his only big studio picture, The St. Valentine's Day Massacre (1967), for 20th Century Fox, Roger Corman returned to work with his frequent collaborators, American International Pictures. The AIP/Corman axis had last produced The Wild Angels (1966), the tale of a motorcycle gang (led by Peter Fonda and Nancy Sinatra) who lived for nothing more than to "get loaded and... have a good time." A change of pace from his stock-in-trade of lush Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, The Wild Angels caught on with young American moviegoers and went on to gross $15 million from an initial investment of $350,000. In follow-up, Corman and AIP chose to make a film that foregrounded a plot point of the earlier film: recreational drug use - specifically lysergic acid diethylamide or LSD (a big hit with the Hells Angels bikers who had served as technical advisors on The Wild Angels. It fell to sometimes Corman actor Jack Nicholson to bang out a screenplay, based on his personal experiences with LSD, the dissolution of his first marriage, and his own Hollywood demons.

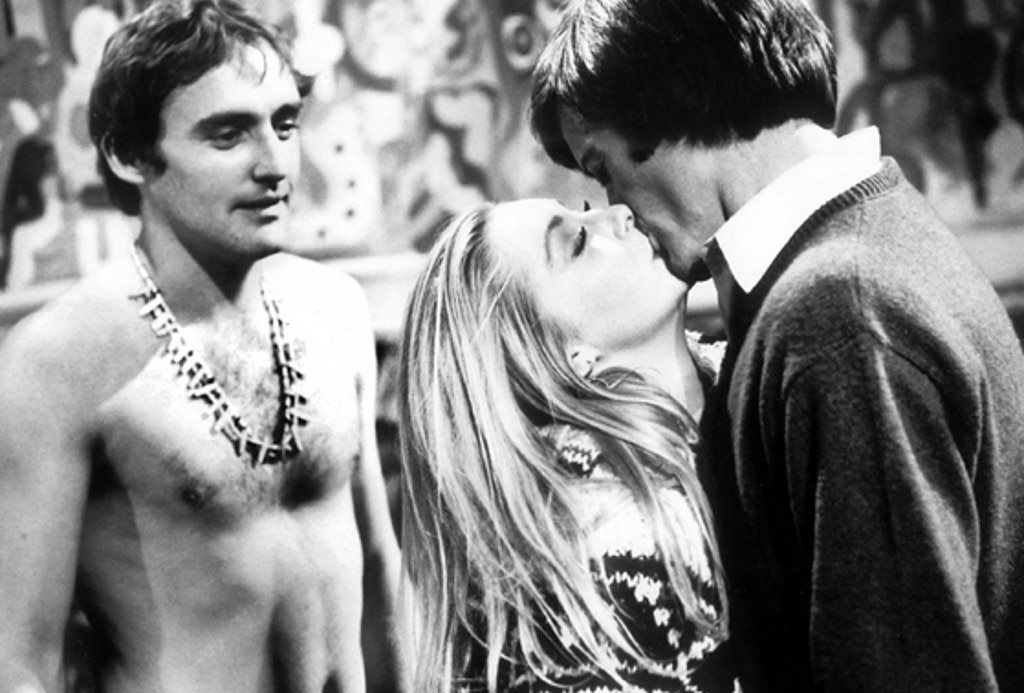

Nicholson wrote the protagonist of The Trip (1967) for his friend, Peter Fonda, who had also experimented with LSD in the company of The Beatles and whose hallucinogen-fueled ramblings ("I know what it's like to be dead!") wound up in the lyrics of John Lennon and Paul McCartney's song "She Said She Said." Without a major studio dictating who he could and could not cast, Corman cast the film with friends and familiar faces, among them Susan Strasberg, Bruce Dern, Dick Miller, Barboura Morris, and Dennis Hopper. Like Nicholson, Hopper's once-promising Hollywood career had stalled due to his own recreational drug use and a reputation for being a problematic actor. Knowing that Hopper had his own filmmaking ambitions, Corman allowed Hopper to direct Fonda in some second unit desert sequences - a dry run, as it happens, for the game-changing independent film the pair would make with seed money from Columbia Pictures: Easy Rider (1969).

Though the logline of The Trip is boilerplate for a standard cautionary tale, Corman's approach to the material was non-judgmental. Wanting to understand his subject from the inside out, the former Stanford engineering major even put himself under the influence of LSD while on a scouting expedition to the craggy coastline of Big Sur, California. In publicity for the finished film, Corman would report to the press that he partook of acid in the company of a doctor, in a strictly clinical setting, but in fact he spent nearly the entirety of his trip face down at the base of an old tree at Big Sur, hallucinating that he had conceived of a new art form in which the intentions of the artist could be grounded with wires connected between the artist's brain and Mother Earth. Though his experience was entirely pleasant, Corman did plumb his own Poe films for Gothic imagery to suggest that not descent into the maelstrom has a happy ending.

Though Corman left the fate of Fonda's character open ended in the final frames of The Trip, AIP founders James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff feared the film would meet with condemnation for its seeming advocacy of recreational drug use. With Corman off in Europe shooting a TV pilot, AIP tacked a disclaimer onto the start of The Trip and superimposed a cracked class optical over a concluding freeze frame of Fonda to suggest that the character's hallucinogenic explorations had done him harm. Corman was furious with the altering of his work (he would break with AIP for good over their meddling with his 1970 hippie satire Gas-s-s: Or It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It) but The Trip turned a considerable profit, earning back $6 million on what had been a meager budget of $100,000. AIP channeled many of the same elements and actors (Strasberg, Nicholson, Dern) into a likeminded follow-up, Psych-Out (1968), directed by Richard Rush. AIP also had first refusal on Easy Rider but Nicholson and Arkoff did not trust Hopper as a director; with Corman interested only in taking a producer's role, the project shifted elsewhere and Corman went on to helm the Depression era gangster saga Bloody Mama, his third-to-last movie before taking a nearly twenty year break from directing.

by Richard Harland Smith

Sources:

How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime by Roger Corman, with Jim Jerome (Da Capo Press, 1998)

'Shooting My Way Out of Trouble': The Films of Roger Corman by Alan Frank (BT Batsford, Ltd., 1998)

Roger Corman: An Unauthorized Life by Beverly Gray (Thunder's Mouth Press, 2000)

Roger Corman Interviews, edited by Constantine Nasr (University Press of Mississippi, 2011)

Roger Corman: Metaphysics on a Shoestring by Alain Silver and James Ursini (Silman-James Press, 2006)

Flying Through Hollywood By the Seat of My Pants: By the Man Who Brought You Was a Teenage Werewolf and Muscle Beach Party by Sam Arkoff, with Richard Trubo (Birch Lane Press, 1992

Jack's Life: A Biography of Jack Nicholson by Patrick McGilligan (W. W. Norton & Company, 1996)

The Trip

by Richard Harland Smith | April 25, 2016

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM