One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest has the distinction of being one of only three films to have swept five of the top Academy Award categories: Best Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Screenplay. It was impressive enough to Academy voters that year to best Nashville (one of the greatest films of its era), the game-changing blockbuster Jaws, Dog Day Afternoon, and Barry Lyndon and put director Milos Forman above heavy-hitters Federico Fellini, Robert Altman, Stanley Kubrick, and Sidney Lumet.

The picture also got scores of awards and nominations from various foreign film boards and domestic and international critics associations, as well as a People's Choice Award for Favorite Motion Picture. According to critic Roger Ebert, at its world premiere in a packed 3,000-seat theater during the 1975 Chicago Film Festival, the reception was so "tumultuous," so much more enthusiastic than Ebert had ever witnessed, that its young, first-time producer Michael Douglas "wandered the lobby in a daze." Years later, it was still garnering acclaim, selected in 1993 for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." What is it about this film that has brought it such high esteem?

To start, one has to go back to the source material, Ken Kesey's best-selling novel of the same name. Although written in 1959 and published in 1962, this tale of oppression and rebellion within an Oregon psychiatric hospital became closely associated with the anti-authoritarian counter-culture of the latter part of the 1960s, containing what film critic Pauline Kael called "the prophetic essence of the whole Vietnam period of revolutionary politics going psychedelic."

Part of that association was due to the author himself, a free-spirited, rambunctious figure who saw himself as a bridge between the Beat Generation and the hippies. By the end of the decade, Kesey's reputation and public persona had outstripped his book and the one other notable work of his career, the 1964 novel Sometimes a Great Notion. His leadership of the legendary Merry Pranksters cross-country bus trip, his presence at Grateful Dead concerts and counter-cultural "happenings," his arrest on drug charges and espousal of psychedelics through the frequent "acid test" parties he threw in the San Francisco area during the mid-60s, all these made him an iconic figure of the times and gave greater resonance to his fictional story of the rebellion of one man, Randle P. McMurphy, against the harsh controls of the mental institution, which came to stand in for all of mainstream American society and its suppression of difference, individuality, and nonconformity.

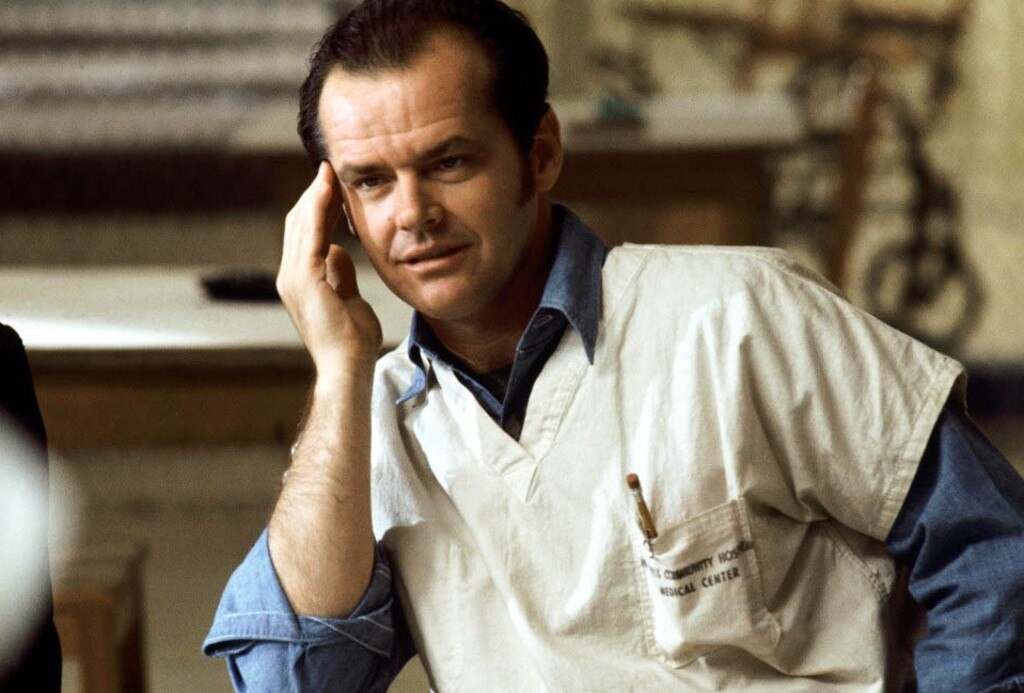

The story, then, came to the screen with all these qualities intact, heightened by the casting of Hollywood's most unconventional leading man, Jack Nicholson. Kesey did not want him in the role, preferring Gene Hackman as McMurphy, but Nicholson amplified the character with his own set of "wild boy" echoes from earlier films--Roger Corman's exploitations of the Haight-Ashbury drug scene (Psych-Out, 1968), biker pictures (not least the countercultural anthem Easy Rider, 1969), and work for several offbeat, independent filmmakers with artistic cachet: Monte Hellman, Bob Rafelson, Hal Ashby, Ken Russell, Roman Polanski, and Michelangelo Antonioni. He added a manic energy that gave perhaps more of a comic spin to the story than Kesey intended, but his identification with the role is absolute. By awarding him an Oscar, Hollywood was touting its acceptance of a singular story and character, and acknowledging that an actor once considered an outsider was now the new standard. As Newsweek put it, "McMurphy is the ultimate Nicholson performance--the last angry crazy profane wise-guy rebel, blowing himself up in the shrapnel of his own liberating laughter."

Against Nicholson's wired mischief, Louise Fletcher was wise to underplay as McMurphy's nemesis, the repressive Nurse Ratched. What could have been a cartoon character was made more chilling by her brilliantly crafted performance, a manifestation of evil and tyranny masked by an outward placidness. The role, and the awards she received for it, proved to be a particular triumph for the actress. Having retired from acting in the early 1960s, she returned a decade later for a couple of television appearances, followed by a supporting role in a film produced by her then husband, Jerry Bick. Thieves Like Us (1974), directed by Robert Altman, turned out to be both lucky and unlucky for her.

Around the time of Thieves... production, Fletcher and Altman began developing a character based in part on her own experience growing up with two deaf parents. It was fully expected she would play Linnea Reese, the mother of two deaf children, in his next film, the sprawling Nashville (1975), but Altman decided to give the part to Lily Tomlin, reportedly after a falling out with Fletcher and Bick. (Tomlin said in 2000 that Michael Douglas had approached her for Nurse Ratched but she didn't get the part.) After Thieves Like Us came out, Milos Forman, the director that Michael Douglas hired for Cuckoo's Nest, went to see it to check out Shelley Duvall for the role of a hooker McMurphy sneaks into the asylum. Forman didn't choose Duvall, but he was impressed enough with Fletcher to cast her as the tyrannical nurse (after Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Colleen Dewhurst, Angela Lansbury, and Geraldine Page said no). Accepting her Best Actress Academy Award, an overwhelmed Fletcher spoke in sign language to thank her parents "for teaching me to have a dream."

Oscar night was the culmination of a long journey for Kesey's book from print to screen. In 1963, a year after it was published, actor Kirk Douglas bought the rights and turned it into a stage production with himself as McMurphy. The play closed on Broadway after 11 weeks (although it did have a successful off-Broadway run in 1971 with William Devane in the lead). Douglas did his best to get a film version going but with no luck. Eventually, he decided that, in his 50s, he was too old to play the lead and turned the rights over to his son.

Michael Douglas was then known primarily as a television actor with a role on the hit police drama The Streets of San Francisco. As unsuccessful hawking the script to the studios as his father had been, Douglas and co-producer Saul Zaentz, a music industry executive eager to transition into film, decided to shop it around as a package. Because that package included Nicholson, a proven draw after Five Easy Pieces (1970), The Last Detail (1973), and Chinatown (1974), they were able to raise the mere $3 million needed to get the picture started. The final cost is estimated to have been more than $4 million. No matter; the picture's gross is said to be 25 to 50 times that amount.

The producers took a big chance hiring a director with art house credentials but no Hollywood track record. Milos Forman, however, knew a little something about oppression and tyranny, albeit on a grander scale than Kesey's story. His parents both died in Nazi death camps during World War II, and his native Czechoslovakia had fallen under Soviet rule after the war. After Warsaw Pact troops invaded Prague to put down a nascent 1968 rebellion, Forman left for the U.S.

By that point, he had already drawn international attention for his distinctive way with social comedies, particularly The Loves of a Blonde (1965) and The Firemen's Ball (1967), and was negotiating to make his first American film. Taking Off (1971) was a critically praised comic take on youthful rebellion told through the eyes of their parents, but it failed to make a dent in the box office. One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest was his breakthrough. The acclaim it brought him led to a career that peaked in the 1980s: Hair (1979), Ragtime (1981), and his second Best Director Academy Award for Amadeus (1984).

The cast of asylum inmates included several virtual unknowns who later made bigger names for themselves, including Danny DeVito (Taxi on TV, the Penguin in Batman Returns, 1992), Christopher Lloyd (also Taxi, Back to the Future, 1985), Brad Dourif (Dune, 1984; Alien: Resurrection, 1997), and Native American actor Will Sampson (The Outlaw Josey Wales, 1976; the TV series Vega$) as Chief Bromden, narrator of the book but silent here.

The artistic crew also contains some notable names. Chief among them is director of photography Haskell Wexler, who came to the production with an Academy Award already under his belt for Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and DP credits on In the Heat of the Night (1967), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), and The Conversation (1974). Wexler was also a director, primarily of documentaries as well as a documentary-like drama set during the violent protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Medium Cool (1969). This was a breakthrough for composer Jack Nitzsche, who went on to write the scores for Cruising (1980), the Michael Douglas adventure comedy Jewel of the Nile (1985), Stand by Me (1986), and The Crossing Guard (1995), which starred Nicholson. He won an Oscar, with wife Buffy Sainte-Marie and Will Jennings, for "Up Where We Belong," the theme song to An Officer and a Gentleman (1982). Nitzsche's score for Cuckoo's Nest earned him his first Oscar nomination.

One name that did not get attention on Oscar night, much to his dismay, was Ken Kesey. "I'd like to have subpoenas in some of those award envelopes," he said, referencing his lawsuit against the producers. Kesey was unhappy from the start, claiming the production was butchering his story and upset it was not being told from the Chief's perspective. Zaentz originally gave him a chance at writing the script. The producers found it interesting, but didn't like the hallucinogenic voice-over by the Chief that Kesey used to tie the story together. It was very frustrating for the author, considering how close he was to the material. The novel came out of his experiences working the graveyard shift as an orderly at a California mental institution, where he got to know the patients and the workings of the facility.

Money was another serious issue. Kesey's suit claimed the producers had promised him 2.5% of the gross instead of the same percentage of the net he was getting. The suit was settled quietly in 1977; Newsweek reported the author was "reasonably satisfied." But on the picture's big night of triumph, he was hurt that his name was never mentioned. "Oscar night should have been one of the great days of my life, like my wedding," he said. "I really love movies. When they can be turned around to break your heart like this, well, it's something you never thought would happen."

"It was a really magical experience for all of us--for everybody except, unfortunately, Ken Kesey," Douglas later said. "That has always hurt me, and it has probably hurt him a lot. It is the only thing about the film that I regret."

By Rob Nixon

Trivia

The book's view of mental illness and criticism of the methods then used to treat it had been controversial, so when Michael Douglas and company sought locations for filming, they couldn't find a state hospital willing to cooperate. They finally found one in Salem, Oregon, where the story was originally set. According to Douglas, the director there "loved and understood the book."

Douglas conceded it would have been much easier to film in a studio, but the location work provided a realism that added tension and texture to the story. The hospital director gave feedback on the characters and their possible problems, then found patients the actors could spend time with.

By the late 20th century, the hospital had fallen into disrepair and disrepute, coming under fire for inadequate programming and deteriorating facilities. It was eventually rebuilt, and in 2012, Louise Fletcher attended the opening of its Museum of Mental Health.

Among the actors considered for the role of McMurphy were Gene Hackman and Marlon Brando, both of whom turned it down. The producers also discussed the possibility of Burt Reynolds.

This was the first feature film script for Bo Goldman, winning him the first of his two Academy Awards. The second was for Melvin and Howard (1980).

When Louise Fletcher first came to Los Angeles, she enrolled in an acting class that also included a young Jack Nicholson.

The picture was also nominated for Academy Awards for editing, cinematography, supporting actor (Brad Dourif), and original score. It won Golden Globes for Best Motion Picture-Drama, Actress, Actor, Screenplay, Director, and Acting Debut (Dourif). It also won six BAFTA awards.

Jack Nicholson's then girlfriend Anjelica Huston (Prizzi's Honor, 1985; The Royal Tenenbaums, 2001) and French actress Aurore Clément (Lacombe Lucien, 1974; Paris, Texas, 1984) had unbilled cameos as two women standing on the pier in the fishing trip scene.

During filming of the fishing trip, Jack Nicholson was the only member of the cast who didn't get seasick.

The Essentials: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

July 07, 2015

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM