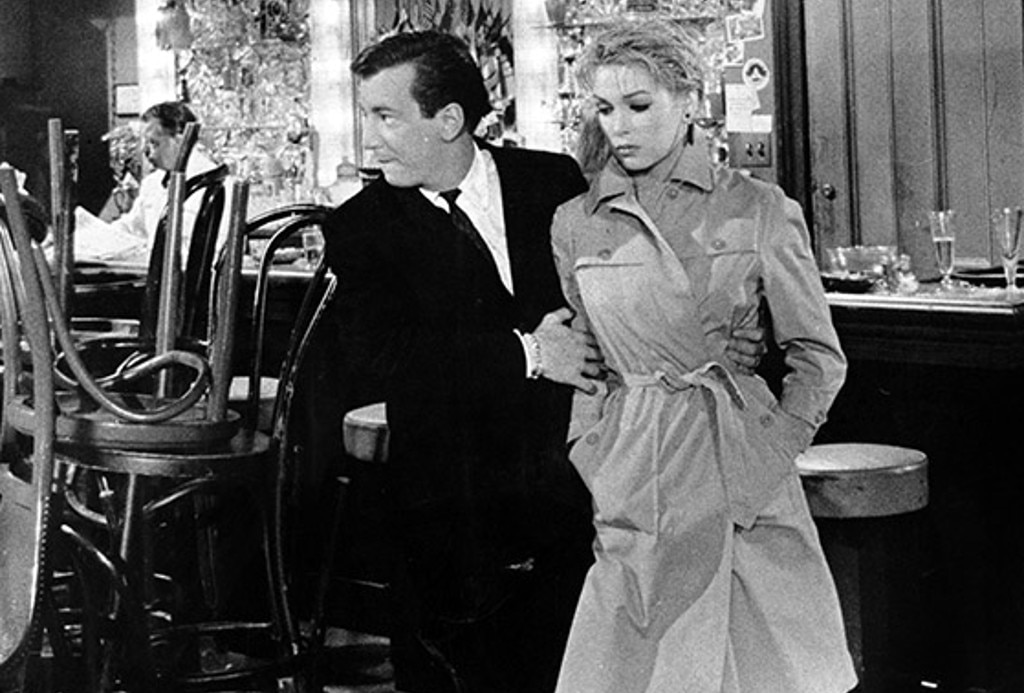

The plot of this 1961 drama, about a cutting-edge jazz musician forced to compromise his artistic principles, could have been a metaphor for actor-turned-director John Cassavetes' experience making his first studio-financed film. The compromises that resulted were something he would regret the rest of his life, while the picture's box-office and critical failure have made it one of the hardest-to-find of all of his films as director. Yet it has also built a cult following over the years for its depiction of the world of jazz musicians always on the cusp of success, the emotionally naked performances of stars Bobby Darrin and Stella Stevens and the telltale signs of Cassavetes' visual style.

Cassavetes was building a solid career as an actor when his first directing effort, Shadows (1959) won the Critics Award at the Venice Film Festival. Made with money raised from friends and family, the film was developed through improvisations about two light-skinned black siblings and the crisis that follows the woman's fling with a white man unaware of her race. The result was a loosely structured, gritty and passionately acted critical hit that some have called the birth of the American independent film movement.

The film's acclaim and Cassavetes' direction of five episodes of his short-lived television series Johnny Staccato brought Paramount Pictures calling with an offer to direct a feature. Almost from the start, Cassavetes clashed with studio executives. He wanted to cast Montgomery Clift as the uncompromising jazz musician. Ghost. and his wife, Gena Rowlands, as the would be singer forced into prostitution when Ghost's combo falls apart. Clift was tied up, however, and the studio insisted on casting Stella Stevens, who had scored positive notices as Appassionata Von Climax in their production of L'il Abner (1959). Pop singer Bobby Darrin, who had played a bit in Shadows, was cast in the male lead. Both acquitted themselves well, and Stevens would later list Too Late Blues as one of her favorite performances. Cassavetes fleshed out the cast with Johnny Staccato's producer, Everett Chambers, in his only film performance, as Darin's bitter agent, future Ben Casey Vince Edwards as a villain who beats Darrin, friend Seymour Cassel as a member of Darrin's jazz combo and Shadows cast members Marilyn Clark and Rupert Crosse.

Cassavetes and the studio also clashed over the shooting schedule. To accommodate his improvisational approach, the director wanted to spend six months on the film. Instead, Paramount held him to just one, requiring him to script the film with Johnny Staccato writer Richard Carr. Ultimately, their work undermined Hollywood formulas. The characters are so human and complex that they make easy audience identification difficult, and the ending is far from the uplifting happy resolution typical of Hollywood films of the era.

Although Cassavetes would later complain about having to work with studio employees who didn't like him or appreciate his approach to filmmaking, cinematographer Lionel Lindon and composer David Raksin did outstanding work on the film. Lindon created a gritty, black and white visual style that helped the film look more improvised than it was. He also met Cassavetes' demand for extensive tight close-ups with some beautifully composed shots that capture the most subtle performance details. Raksin, who had written lush symphonic scores for films like Laura (1944) and The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), came through with a powerful jazz score. He also engaged such jazz legends as Benny Carter and Shelly Manne to record the performances for Darin's combo.

The film was so far from what Paramount executives expected they sent it directly to neighborhood theatres, where it did poorly at the box office. Reviewers at the time weren't much more enthusiastic. The New York Times called it a "curious but sordidly fascinating fragment of a film." Although they praised Cassavettes' creation of atmosphere and the performances, they decried the lack of sympathy generated for the lead character and the inconclusive conclusion. Variety wasn't much better, praising the score and a party scene, but complaining of "a tendency to force casebook psychology on the characters that robs the film of spontaneity."

More recently, however, the few critics able to see the rarely screened film have found much to love. Time Out has called it "one of the more impressive Hollywood movies to be set in the hip, flip jazz world" and praised the scenes of conflict between Darin and his combo members. On the CinemaRetro web page, Dean Brierly hails it as "a lost Cassavetes classic" and claims "its stylistic daring and the emotional depth charges set off by its lead actors transcend the film's limitations. Indeed, its very awkwardness serves to underscore the instability of its ambitious yet emotionally stunted characters. The few souls lucky enough to have witnessed the minor miracle that is Too Late Blues find that it lodges in the memory with the persistence of a jilted lover." For its more recent fans, any chance to view the film has become an occasion.

Producer-Director: John Cassavetes

Screenplay: Richard Carr & Cassavetes

Cinematography: Lionel Lindon

Score: David Raksin

Cast: Bobby Darrin (John 'Ghost' Wakefield), Stella Stevens (Jess Polanski), Everett Chambers (Benny Flowers), Nick Dennis (Nick Bobolenos), Vince Edwards (Tommy Sheenan), Marilyn Clark (Countess), Rupert Crosse (Baby Jackson), Seymour Cassel (Red), John Cassavetes (On-Screen Trailer Host & Narrator), Ivan Dixon (Party Guest)

By Frank Miller

Reference:

Brierly, Dean. "Too Late Blues: Dean Brierly...Celebrating Films of the 1960s & 1970s." Cinema Retro, October 8, 2013, http://www.cinemaretro.com/index.php?/archives/196-TOO-LATE-BLUES-DEAN-BRIERLY-REVISITS-A-LOST-GEM.html.

Too Late Blues

by Frank Miller | December 16, 2014

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTERS

CONNECT WITH TCM