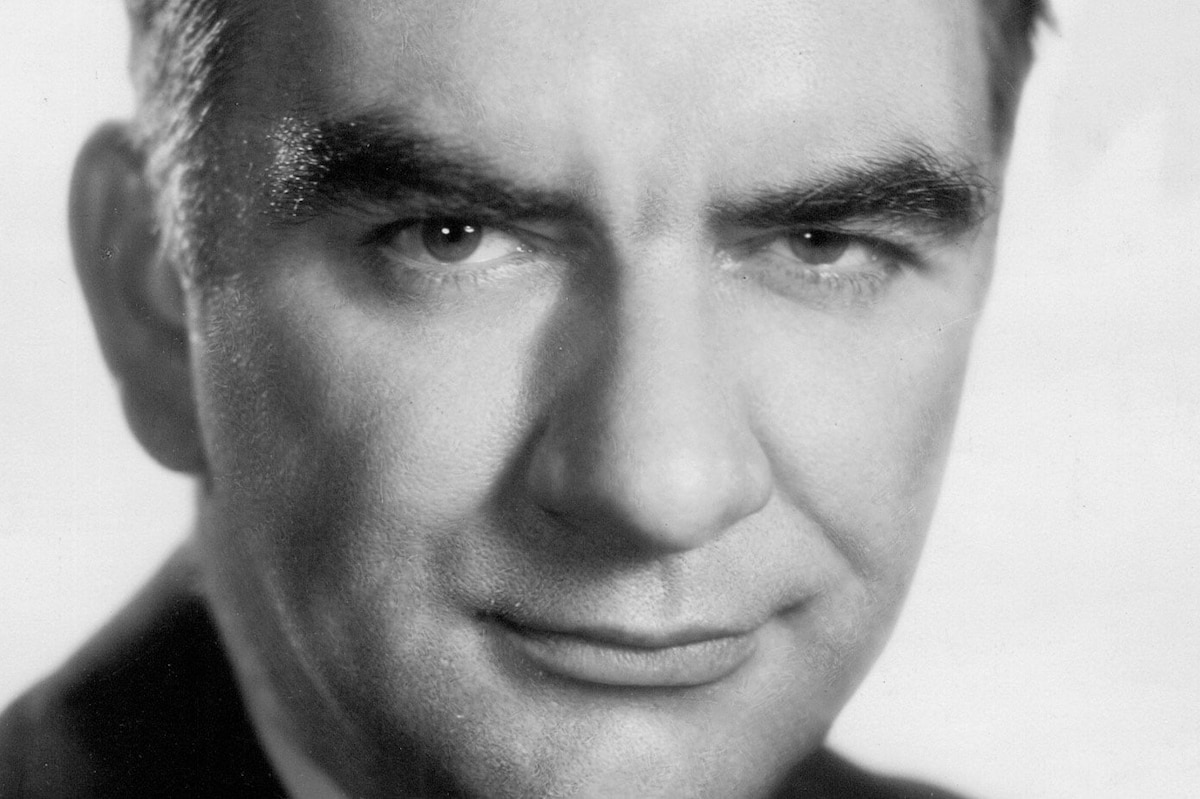

In 1941, literary critic Edmund Wilson wrote a piece for The New Republic entitled “The Boys in the Back Room,” placing the novelists Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain into a grouping of preeminent writers of hard-boiled crime fiction, a genre that had exploded in popularity. They were “poets of the tabloid murder,” Wilson wrote. All three authors’ writings would soon play vital roles in the emergence of film noir, but Cain in particular bristled at his work being called “hard-boiled.”

“Let’s talk about this so-called style,” Cain said in a 1977 interview for The Paris Review. “I don’t know what they’re talking about— ‘tough,’ ‘hard-boiled.’ I tried to write as people talk... There’s more violence in ‘Hamlet’ than in all my books. I write love stories, and about the wish that terrifies.” Nonetheless, his reputation as a tough-guy writer has endured, not just from his novels but from three all-time-classic film noir dramas that were made from them: Double Indemnity (1944), Mildred Pierce (1945), and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946).

Cain worked as a journalist throughout the 1920s, and for the rest of his life considered himself foremost a “newspaperman.” In 1931, after serving a nine-month stint as managing editor of The New Yorker, he departed for Hollywood and a six-month contract at Paramount. Over the 15 or so years he lived in Los Angeles, Cain was contracted at various studios and mostly rewrote scripts without credit. While he never found real success as a screenwriter, he also devoted time in L.A. to writing magazine articles, short stories and novels that would secure his fame.

His first, published in 1934 when Cain was 42 years old, was “The Postman Always Rings Twice.” The tale of adultery and murder, with shocking-for-the-era sex and violence, was a spectacular bestseller and critical sensation. Cain biographer Roy Hoopes later wrote: “‘Postman’ was probably the first of the big commercial books in American publishing, the first novel to hit for what might be called the grand slam of the book trade: a hard-cover bestseller, paperback bestseller, syndication, play, and movie. It scored more than once in most of these mediums.”

Hollywood would have to wait more than a decade, however, before making its first film version. (Other screen adaptations were made in the meantime in France and Italy.) Cain’s agent sold the novel upon publication to MGM, but the Hays Office turned it down flat, refusing to grant the necessary stamp of approval.

This happened all over again in 1936, when Cain’s novella “Double Indemnity” was serialized in Liberty Magazine. Another sordid, juicy tale of adultery and murder, Cain said he wrote it “very slapdash and very quick—I had to have money... I was flat broke. To make money quick I thought, well, ‘you can do a serial for Liberty,’ and the idea for this thing popped into my head.” Studios all over Hollywood expressed tremendous interest. Once again MGM asked the Hays Office for their report on the story, and once again the Hays censor Joseph Breen outright rejected it. “Under no circumstances,” he said, would “Double Indemnity” ever be approved, for not only did the story lay out a veritable blueprint for murder, but the adulterous couple got away with it. Cain resigned himself to “Double Indemnity” being “the most censorable story, if any story is censorable, I ever wrote.”

Cain continued writing, turning out the even more “unfilmable” novel “Serenade” in 1938, “Mildred Pierce” in 1941, and then a book, “Three of a Kind,” in 1943 that compiled three novellas including “Double Indemnity.” The book drew renewed interest from around Hollywood, and when Billy Wilder learned that his secretary had become smitten with the book in galley form, he read it one night and immediately set about acquiring the screen rights for $15,000 (ten thousand less than the sale price would have been a decade earlier—a loss which Cain resented forever after).

Wilder adjusted the tone and narrative angles of Cain’s novella to result in a screenplay that won approval from the Hays Office. Wilder wrote the screenplay with Raymond Chandler. Cain later said he was never asked to write the script, but he did participate in a story conference. He said that Wilder was frustrated with Chandler for rewriting so much of Cain’s dialogue. “To try and prove his point,” Cain recalled, “he got three contract people up, and they ran through these scenes with my dialogue. But to Wilder’s astonishment, he found out it wouldn’t play.” As Cain admitted, his story had been “written for the eye,” not the “ear.”

The resulting movie, released by Paramount, was a huge commercial and critical success, nominated for seven Oscars. After stars all over Hollywood turned the project down for fear of ruining their careers, Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck came aboard for their second of four film pairings. They are sensational as the lustful, scheming Walter Neff and Phyllis Dietrichson, and the film is considered one of the most important in the development of the film noir style. Other movies now recognized as “noir” had already been released, but Double Indemnity was really the first to bring all the elements of the movement completely together. The shadowy, low-key cinematography of John F. Seitz, combined with the script’s outrageously entertaining double entendres, Wilder’s skilled creation of suspense, Miklós Rózsa’s memorable score, MacMurray’s doomed sap and Stanwyck’s cold femme fatale, inspired an unleashing of similar movies from all over Hollywood.

In fact, two of the next major noirs were Warner Bros.’ Mildred Pierce (1945) and MGM’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, cementing Cain’s reputation and fame even more strongly. With Double Indemnity, the Hays Office had set a precedent for accepting adultery and implied sex in a way they had not previously, and so they couldn’t readily complain so much about the sexiness and shocking violence of this story. All the same, Postman director Tay Garnett later explained his take on why the Hays Office approved the script: “The thing [they] objected to in the original was the sort of low-level quality of the people in it. We’ve raised the tone of the story. I guess you could say we’ve lifted it from the gutter up to, well, the sidewalk.”

Postman is the tale of a drifter, played by John Garfield, who takes a job at a roadside diner run by married couple Cecil Kellaway and Lana Turner, who appears in one of the steamiest performances of the 1940s. Turner and Garfield start a torrid affair and plot to kill Kellaway. The screenplay was adapted by Harry Ruskin and Niven Busch and the film became another enormous commercial success, even if it is considered to be a slight notch below Double Indemnity in its overall quality.

The three major films made in succession from three sordid Cain novels prompted The New York Times to invite him to write an article about how it had happened. “The stories were not toned down,” Cain wrote. “Of the three I would say Double Indemnity stuck closest to my story, with The Postman Always Rings Twice next closest and Mildred Pierce least close. But all three stuck closer than the average picture does to the material from which it is adapted. In each, naturally, details about sex were omitted, but they are pretty much omitted in my novels, it may surprise you to learn. People think I put stark things in my stories, or indulge in lush descriptions of the heroine’s charms, but I don’t. The situations...are often sultry, and the reader has the illusion he is reading about sex. Actually, however, it gets very little footage.”

Later on, he said of Double Indemnity, “I must say Billy Wilder did a terrific job. It’s the only picture I ever saw made from my books that had things in it I wish I had thought of. Wilder’s ending was much better than my ending, and his device for letting the guy tell the story by taking out the office dictating machine—I would have done it if I had thought of it.” He added that he also wished he had thought of the suspenseful scene where MacMurray opens the apartment door to let out Edward G. Robinson, and Stanwyck has to hurriedly hide behind it.

Cain said, “To write anything, I have to pretend to be somebody else... My difficulty in writing a story is not in thinking of something to write about, but in finding a reason this character in the first person would tell it. That’s my problem. It doesn’t have to be a very important reason; it can be the most special, cockeyed reason in the world that wraps up in a sentence or two. But just the same, I have to have that or I can’t tell the story.”

“I write of the wish that comes true, for some reason a terrifying concept, at least to my imagination...I think my stories have some quality of the opening of a forbidden box.”