In partnership with The Film Foundation, iconic film director and classic movie lover Martin Scorsese's exclusive monthly contribution to the TCM newsletter Now Playing in July 2022.

On two Friday nights this month, TCM is paying tribute to Stanley Kubrick, who would have turned 94 on July 26th. They are showing eight of the 13 features he made between 1953 and 1999, the year he passed away unexpectedly at the age of 70 as he was finishing Eyes Wide Shut.

When Kubrick was alive and working, it was easier to get ambitious films into production than it is now, and many people were puzzled over the years that passed between his projects. If you’re just paying attention to numbers, then no, Kubrick was far from prolific. But each one of his pictures has the scope and vastness of an entire body of work by someone else, particularly the ones from Dr. Strangelove on. What is it exactly that sets Kubrick apart? His mastery? The extraordinary breadth of his knowledge? His ability to build action that plays out on multiple levels—funny, horrifying, ironic, dramatic, real and dreamlike, all at once? These are remarkable qualities, but I think there’s something else.

In Kubrick’s greatest films, every corner of the frame in every shot has been painstakingly realized, and the same goes for every line reading, every gesture, every movement of the camera. Each element contributes to the creation of a whole complex world. But it’s the complexity of what’s happening offscreen that puts the films in a class by themselves.

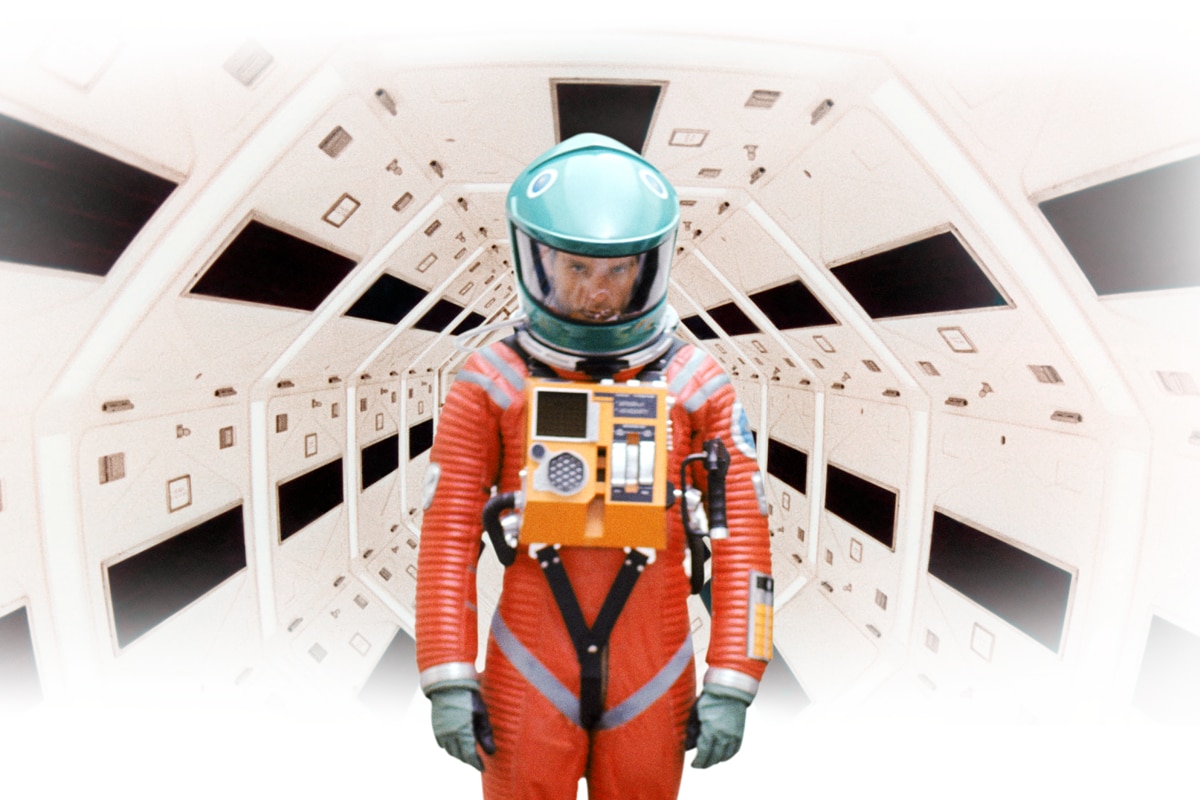

The story that we’re watching seems to be part of a much larger story, determined and controlled by forces that we can neither see nor comprehend, but that we intuit and sense. The prime example is 2001, in which the “story” is two series of events, millions of years apart, in the history of humankind on earth, linked by the appearance of the monolith…which indicates the presence of a mysterious power beyond our capacity for understanding.

In The Shining (which for some reason has been left out, along with The Killing and Full Metal Jacket), what is actually happening? Cabin fever, paranormal communication, a curse that possesses the caretakers at the hotel…okay. But these are elements that we’ve known and experienced in other movies. In The Shining, there seems to be something more disturbing and omnipotent at work, embodied by that startling image of the blood gushing from the elevator.

You could say the same of Barry Lyndon or Dr. Strangelove—in the “technologically advanced,” “civilized” worlds of those pictures, where everything looks so perfectly ordered and managed, there are offscreen furies driving us to cruelty, murder and self-annihilation. And there’s always the sense that the world we’ve created for ourselves will eventually topple and be reduced to rubble and dust, just like Rome or Babylon.

But Kubrick was also something else: a master entertainer. His pictures are exhilarating experiences, each one casting its own unique spell. They’re also very, very funny, with deep roots in the great tradition of Jewish standup comedy. Contrary to the old clichés about Kubrick being chilly and cerebral, he seems more and more human to me all the time. I can’t think of many artists who have brought us so close to the reality of our collective condition.