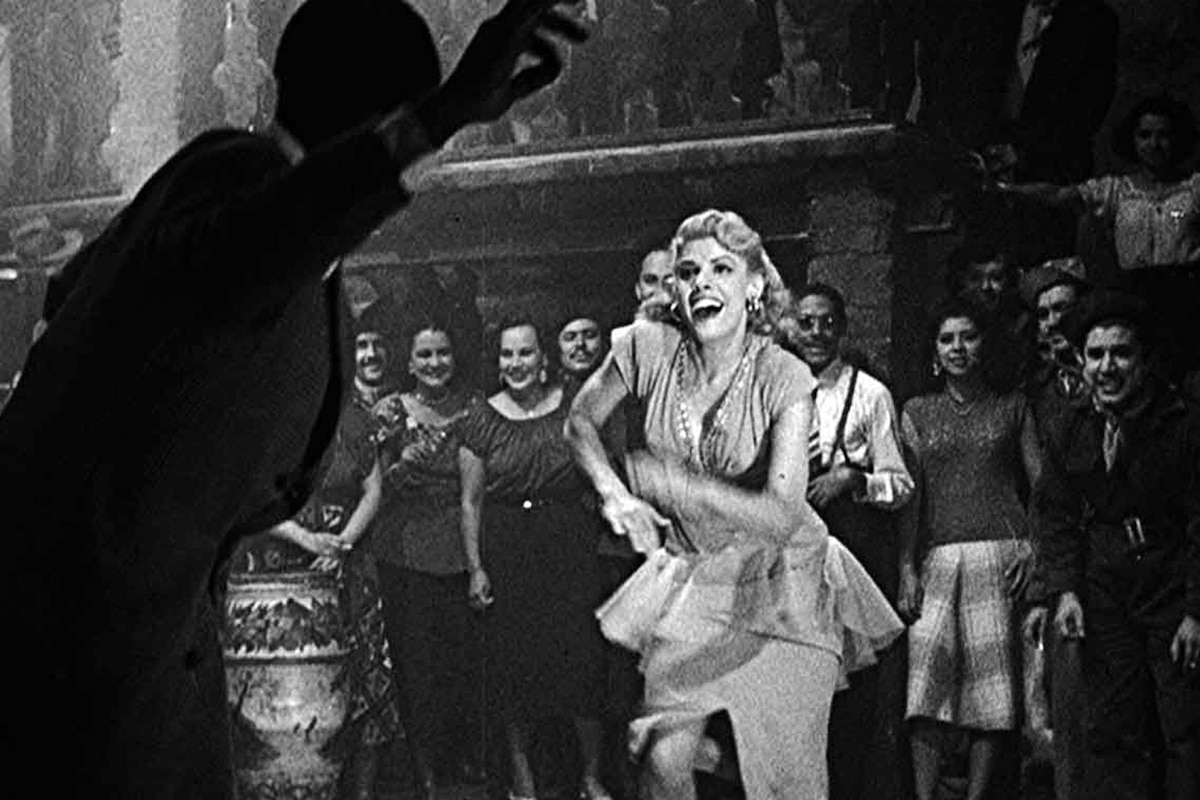

Music, murder and high-pitched emotions collide in this feverish film from the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. With low-key cinematography from the legendary Gabriel Figueroa and musical performances from such Latin American superstars as leading lady Ninon Sevilla, singers Rita Montaner and Pedro Vargas, and dancer Perez Prado, the 1951 film is a treat to the eyes and ears. Sevilla’s performance and Figueroa’s cinematography have helped make it a cult favorite as contemporary audiences are re-discovering the treasures of Mexican film.

The plot centers on Violeta (Sevilla) a musical performer working at the Club Chango. After she finds a baby in a garbage can, she decides to raise it as her own, much to the displeasure of the pimp Rodolfo (Rodolfo Acosta) who had forced the child’s mother to throw it in the garbage in the first place. Her devotion to the child not only costs her job but also leads to a life of prostitution and continuing conflict with Rodolfo, who even cuts up her face. Her only support is Santiago (Tito Junco), the owner of a rival club who’s fallen in love with her. Can she find happiness with her new man, or will Acosta continue to disrupt her life?

Historians tend to disagree as to when the Golden Age of Mexican cinema began and ended, though whatever dates they use, Victimas del Pecado falls within that era. Historians are instead more united on the factors that caused it. In 1942, Mexican president Miguel Avila Camacho created the Banco Cinematografico to fund film production. At the same time, Mexico’s entry into World War II as a U.S. ally gave it access to film stock and equipment to a greater degree than previously. This led to an explosion of Mexican film production and the rise of major studios in Mexico City. Before long, Mexico was the chief supplier of films for Latin America and had developed major filmmakers and stars to rival any in Hollywood. Mexican films also developed genres of its own, including the rumberas or peliculas de cabareteras (“cabaret dancer films”) inspired by the popularity of mambo music and dancing.

Victimas del Pecado was one of the most popular of the rumberas. The genre showcased music from the African and Caribbean traditions, with a particular emphasis on dance numbers. In this case, the most spectacular dancing is provided by Sevilla and Prado, one of the greatest of the mambo kings. The stories revolve around the female characters, usually women born in the country but forced to find their way in the city, which reflects Mexico’s move from a rural to an urban society in that period. Seduction, prostitution and murder figure heavily in their plots alongside singing and dancing, with musical performance becoming the ultimate redemption for fallen women.

Leading lady Sevilla was one of the biggest female stars of Mexico’s Golden Age. She was born in Cuba, where she established herself as a top nightclub attraction. Calderon Films brought her to Mexico, where she made her film debut with a supporting role as a gangster’s moll in Pecadora (1947). Her musical numbers stole the show. By her third film, the comedy La Feria de Jalisco (1948), she had moved into starring roles, but it was in her next film, Revancha (1948), that she claimed her position as one of the queens of the rumberas. She reigned for over a decade, starring in a series of musical melodramas for which she choreographed her own dance numbers. Her fame even reached non-Spanish-speaking countries, making her a favorite in Brazil and France.

By the end of the 1950s, Mexican society had taken a more conservative turn. Nightclub culture was on the decline, and the genre fell out of fashion. Sevilla retired and moved to New York until the 1980s, when she scored a major comeback played an aging cabaret star in Noche de Carnaval (1984). The role won her the Ariel Award, Mexico’s version of the Oscar. She finished her career making telenovelas.

Victimas del Pecado’s director Emilio “El Indio” Fernandez had helped put Mexican cinema on the map. He was born to a revolutionary general and a descendant of the Kikapu nation in Sabinas, Coahuila, Mexico. Like his father, he served in the revolutionary army in the 1920s. When the uprising against President Obregon failed, he was sent to prison but escaped, fleeing the country and eventually winding up in Hollywood, where he worked as an extra and stand-in. Legend has it he even posed for the Oscar statuette, a job he got through his friendship with Dolores del Rio, who would eventually marry the Oscar’s designer, art director Cedric Gibbons.

When he was granted amnesty, Fernandez returned to Mexico, where he became a major film star in the 1930s. Influenced by the films of Sergei Eisenstein, whose work he had seen in Hollywood, he moved into directing in 1941, eventually creating an artistic partnership with writer Mauricio Magdaleno, cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa and actors Pedro Armendariz and del Rio. Their first film together, Flor Silvestre (1943), was an historical drama that marked Del Rio’s first appearance in a Mexican film. They followed it with Maria Candelaria (1944), an international sensation that won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival and is often cited as the birth of Mexico’s Golden Age.

His first rumbera was Salon Mexico (1949), the success of which led Calderon Films to ask him to direct Sevilla in Victimas del Pecado. Fernandez’ career declined in the late 1950s, when his approach began to seem old fashioned. There was also a rumor that he had shot a critic in the groin, which put his directing career in trouble. He returned to acting in 1959 and appeared in such U.S. productions as The Night of the Iguana (1964), The Appaloosa (1966) and The Wild Bunch (1969).

Victimas del Pecado was a big hit, although it aroused the ire of the Catholic church, whose reaction prefigured the growing conservatism that would end the rumberas’ popularity. It was also a favorite in France and Belgium. Most of Mexico’s Golden Age films did not find art-house distribution in the U.S. The film made its U.S. premiere in 1989 at the Berkeley Art Museum, where it was praised for Sevilla’s performance, the film’s high level of emotionalism and Figueroa’s cinematography. It was also part of a retrospective of Fernandez’ career at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018.

Producers: Guillermo Calderon, Pedro A. Calderon

Director: Emilio Fernandez

Screenplay: Fernandez, Mauricio Magdaleno

Cinematography: Gabriel Figueroa

Score: Antonio Diaz Conde

Cast: Ninon Sevilla (Violeta), Tito Junco (Santiago), Rodolfo Acosta (Rodolfo), Rita Montaner (Rita), Ismael Perez (Juanito), Margarita Ceballos (Rosa)