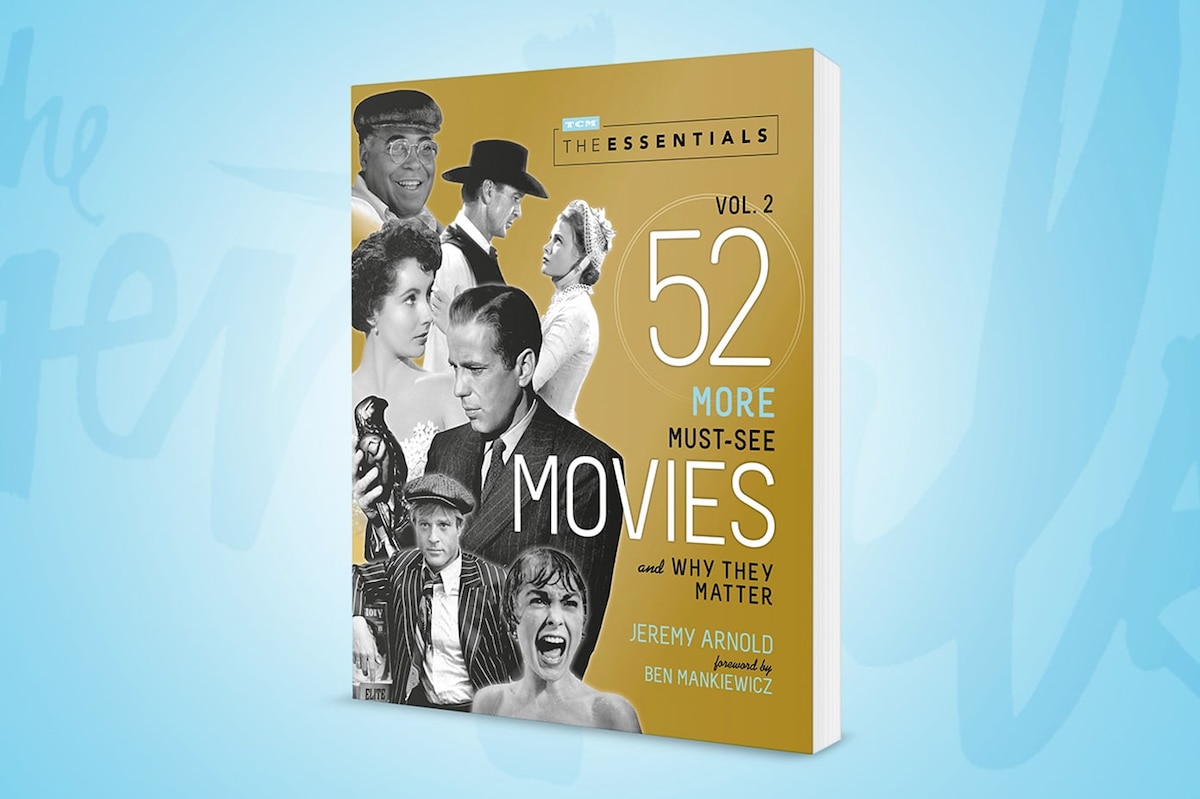

Anyone who has watched TCM’s The Essentials series over the past 20 years knows that “essential” films come in all shapes and sizes and have shown themselves to be essential for all kinds of reasons. Among the most fascinating are the pictures that underperformed at the box office, ranging from mild disappointments to outright duds. Some of them were critically acclaimed but still didn’t find an audience; others were reviled by critics, too. Yet they have endured and continue to have the last laugh, so to speak, as their craft and artistry have outlasted the apathy or venom of their day. Here are eight such films I included in my new TCM/Running Press book The Essentials Vol. 2: 52 More Must-See Movies and Why They Matter.

Freaks (1932)

It’s a safe bet that no one involved in the making of Freaks could have imagined that this picture would be lauded or even seen by audiences and film scholars nearly 90 years on. It was lambasted by all in its day and heavily cut by its studio, MGM (an unlikely producer for this kind of film), reducing but not eliminating the effect that director Tod Browning had been aiming for. Browning had great compassion for the real-life, disabled “freaks” at its center; he lends them dignity. It’s to his credit that his film, despite the edits, continues to challenge our reactions, forcing us to reckon with the contrast between outer appearance and inner life.

Twentieth Century (1934)

Howard Hawks’ brilliant early screwball comedy was even screwier than It Happened One Night, which had opened a few months prior from the same studio, Columbia. Based on a satirical Broadway hit by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, it, alas, proved Variety’s prediction that it was “too smart for general consumption.” The film never caught on with audiences but now has its place as one of the funniest comedies of the 1930s, thanks in no small part to the chemistry between Carole Lombard and John Barrymore, whom Lombard said taught her more about screen acting than anyone else in her life. All the same, critics loved the movie, and Hollywood took notice of this fledgling genre, soon churning out more screwball classics like The Awful Truth, another Essential which became the biggest hit of 1937 (and is also in this book).

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947)

Not a dud, but not a particular success, either. Gene Tierney was now the top dramatic star at Fox, having just starred in her Oscar-nominated Leave Her to Heaven (1945), Dragonwyck (1946) and The Razor’s Edge (1946), all of them hits. The Ghost and Mrs. Muir was a more modest film – with a quieter type of performance – that proved underwhelming. The film came and went. But it has endured thanks to its exquisite craft and sensitivity, expressed through director Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s visual choices, Bernard Herrmann’s exquisite score and Tierney’s understated emotional pull, all of which contribute to an almost visceral sense of yearning. It stands now as one of the most beautiful romantic films of its era. Truly a film that seems to grow in popularity every year as it is discovered by newer audiences.

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Dismissed as a distasteful cheapie in 1955, this sensational, exhilarating film noir directed by Robert Aldrich positively drips with atomic-age paranoia, making it a fascinating glimpse into the anxieties of the time. Its audacious style and shocking violence, most of it implied offscreen, also made it far ahead of its time. Even its screenwriter, A.I. “Buzz” Bezzerides, said he had “contempt” for the source material, a pulp novel by Mickey Spillane. “So I went to work on it,” he said. “I wrote it fast... Things were in the air at the time, and I put them in.” Paranoia over atomic weapons and the McCarthy witch hunts and Hollywood backlisting heavily informed the feel of this film, which finds private eye Mike Hammer working his way up a chain of brutal gangsters in search of “the great whatsit,” a mysterious boxed item somewhere in Los Angeles. The explosive finale is positively transcendent. Thankfully, audiences and critics have long since made right by this film, which is now seen universally as an influential classic and touchstone.

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

This is the saddest case of box-office failure in the book because the chasm between the film’s brilliance and its reception was so vast. Charles Laughton took the directing reins for the first time – and the only time, due entirely to his depression over the way the film was received. It’s a spellbinding thriller told with the intentional feel of a child’s nightmare, as if a kid were living out his worst fears as a film noir with Robert Mitchum as the terrifying boogeyman at its center. Mitchum plays a deranged “preacher” who terrorizes a young brother and sister in Depression-era Appalachia, even worming his way into their family simply to find out where they hid their now-dead father’s stolen money. The kids flee down a river and wind up in a home of orphans run by tiny foster mother Lillian Gish, who will prove to be a mighty match for the hulking Mitchum. A parable of good and evil, with fears, dreams and nature’s magic looming larger than life in the way such things do in the eyes of children, The Night of the Hunter is a mesmerizing piece of art that was practically laughed off the screen. Its pictorial beauty, created by cinematographer Stanley Cortez, blended with a terrifying sense of menace has since been rediscovered and appreciated by growing audiences.

A Face in the Crowd (1957)

Playwright George S. Kaufman once said, “Satire is what closes on Saturday night.” Certainly, that applies to the box-office disappointment of Twentieth Century and the complete, outright failure of A Face in the Crowd. Directed by Elia Kazan and written by Budd Schulberg, this film has gotten much attention in recent years for its prescience as it relates to current politics, with its story of an Arkansas jailbird named Lonesome Rhodes who ascends to the heights of media, celebrity and political culture by fooling untold numbers of Americans, who believe him to be an honest man of the people and not a corrupt charlatan. The movie vanished quickly in 1957, but its predictions of television helping to blur the roles of entertainer, populist, influencer, pitchman and politician have long since come true.

Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

“Don’t touch a foot of this film. Burn the whole thing.” According to writer Ernest Lehman, that’s what one audience card said after a preview screening of this picture, another instance of a great gulf between initial reception and modern-day reverence. Dark, cynical and brutal (in attitude and language more than in physical violence), Sweet Smell of Success is one of the great movies about power. Pure, unbridled power that, when blended with mass media, becomes ever more intense and corrupts its wielder to ever deeper degrees. Burt Lancaster is vicious as J. J. Hunsecker, a gossip columnist who can make or break celebrities, politicians, cops, even two-bit operators, according to his whim. Tony Curtis is the obsequious press agent, Sidney Falco, trying to curry favor with J.J. in order to further his own career. The amorality of the characters, combined with a heavy atmosphere of cynicism and corruption, was seen as distasteful and unpleasant at the time but is lauded as brilliant art today. James Wong Howe’s film noir cinematography is a perfect expression of the attitudes at play and also makes this one of the essential New York movies.

Vertigo (1958)

Another classic that was not exactly a dud upon release but did not do especially well, which is surprising for a film now considered in some quarters to be the greatest film ever made. As with Lancaster’s performance in Sweet Smell of Success, James Stewart in Vertigo is for some audiences a tough turn to take. His obsessiveness and unhinged quality are disturbing to the point of off-putting to some audiences – yet the performance is also brilliant to many others and in keeping with Stewart’s decades-long exploration of the darker aspects of his persona. Alfred Hitchcock’s romantic thriller adroitly explores the intersection of reality, illusion and fantasy in such a way that the audience experiences–visually–the shock of that blend as do the characters played by Stewart and Kim Novak, who is heartbreakingly vulnerable in a dual role.